The History of CU Anschutz School of Medicine

The History of CU Anschutz School of Medicine

The School of Medicine began humbly in 1883 with two students and two professors. Today it’s part of a vast new campus with state of the art research facilities.

The school was founded in Boulder and moved in 1924 to Colorado Boulevard and Ninth Avenue in Denver.

In 2008, the school transformed itself again with a move to Aurora.

The medical school now is part of a bioscience center that also includes schools of dental medicine, pharmacy, public health and nursing. The campus includes three research towers, the University of Colorado Hospital and Children’s Hospital Colorado and a new Veteran's Hospital campus.

The Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute tries to quickly apply laboratory breakthroughs to people’s lives.

And remember those two med students in 1883?

A detailed history of the School of Medicine

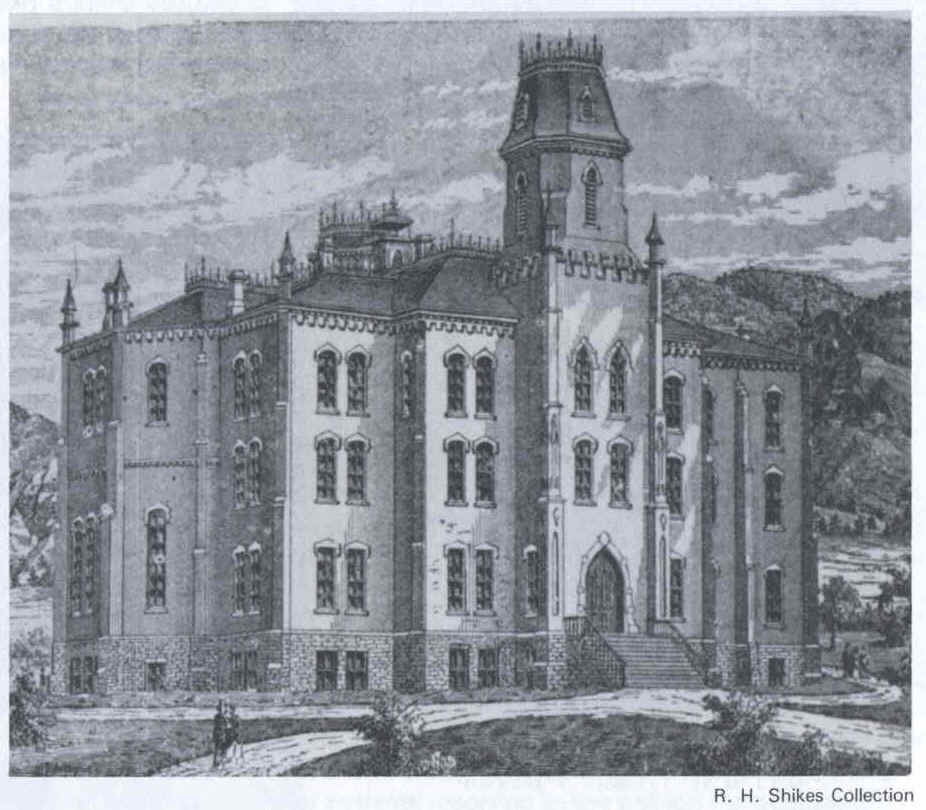

The year was 1883, and while the physical plant was nothing to brag about, the faculty student ratio was incredible: What we now call the University of Colorado School of Medicine started with two professors teaching two students on the University of Colorado CU Boulder campus.

Today, the School of Medicine operates on a new campus in Aurora.

It’s where Tom Starzl, MD, conducted the first liver transplant in the world. Where Ted Puck, MD, developed a classification system for human chromosomes. Where Henry Swan, MD, stuck a patient in a bath tub of water cold enough to slow the patient’s pulse and revolutionize open-heart surgery. Where Henry Sewell, MD, founded immunology.

But it is also the place that lost every cent of its state funding only a few years after the Colorado General Assembly decided the state needed a medical school.

It is the place where Ku Klux Klan powerbrokers in the legislature once tried unsuccessfully to tie state funding to an order that the university fire all the “Jews and Catholics” on his faculty.

It is the place that ranks near the bottom nationally in per capita state funding.

A bold move to Denver

The move from Boulder to, initially, Denver capped a decades-long struggle to see which - if any – of Colorado’s four turn-of-the-20th-century medical schools would survive.

When the School of Medicine tried to send its Boulder-based students to Denver for clinical training (Boulder did not have enough), officials at the private University of Denver Medical College and Gross Medical College and the Denver Homeopathic Medical College cried foul.

The private schools took the state university to court and won. The university’s state charter said all teaching had to be done in Boulder.

But the first University of Colorado Hospital, a 30-bed unit built in Boulder, simply couldn’t measure up. Neither did its 40-bed replacement. It was move or die. Helped along by Dean William Harlow, MD, an amendment to the state constitution in 1912 finally allowed the School of Medicine to teach its third- and fourth-year students in Denver.

In 1924, the entire four-year medical school, by then under the leadership of Dean Charles Meader, MD, moved from Boulder to a new campus in Denver. The state-of-the-art campus near Colorado Boulevard and Ninth Avenue assured the school’s survival in the near term.

The quadrangle of red brick buildings that made up that campus are now mostly abandoned and have become a retail/residential development. But at the time of their construction they were just what educators of doctors ordered.

There was a medical school, a nursing school and a public teaching hospital that cared for those too poor to pay. But it took the United States winning a war to truly bring the medical school the success that insured its future into the 20th century.

"The most important thing that happened to this school was the development of a fulltime faculty after World War II,” said Henry Claman, MD, who co-authored a biography of the School of Medicine.

A physician recruited from the faculty of the medical school at Washington University in St. Louis oversaw the gilding of the institution. Robert Glaser, MD, became the School of Medicine’s Dean in 1957. He served in that capacity until 1963. Glaser profited from a national era of optimism in 1950’s America.

“There was money available from the National Institutes of Health and other federal agencies,” said medical historian Bob Shikes. “Things started to boom in academic medicine in the 1950’s.”

Glaser turned the boom into an explosion by recruiting talented department chairs who, in turn, attracted talented faculty and staff to their departments. The medical school expanded not only the size and quality of its faculty, but the size and quality of its student body and in the size and quality of its physical plant.

"When I got here in the 1960’s, the school had achieved critical mass,” Shikes said. “Amazingly, it became one of the Top 25 medical schools in the country. That’s very good for a state that gives nothing.”

The deans who succeeded Glaser oversaw an expansion in scope, though never a great boost in state funding. But the medical school’s existence was never endangered, due primarily to the accumulation of renowned doctors working in several of its departments.

The Krugman era

Richard Krugman, MD, served as an interim dean from 1990 to 1992 before being officially appointed to lead the school. Krugman retired in 2014.

“What was clear in the '90s and what is clearer today is that medicine is no longer departmentally based,” Krugman said. “Department chairs and medical centers have to work with each other, not against each other.”

Krugman made peace between rival departments. He reorganized the clinical practices of faculty and increased the graduation rate of primary care doctors in response to Colorado’s need for them. But his main goal was simple:

“The job of the dean,” he said, “is to provide the space and resources for the faculty and students to do their work.”

From his vantage point as a medical historian, Claman agreed in part.

“The faculty is the heart of the School of Medicine, because the students come and go,” Claman said. “From the standpoint of faculty, the dean provides the right atmosphere to do work.”

Unfortunately, atmosphere means little without money to sustain it, and funding remains a complex dilemma. State dollars are especially tight given the tough economy and the demands and restrictions voters have put on Colorado’s budget.

“What we accomplished during a time of unprecedented state cuts is an extraordinary testimony to the faculty,” Krugman said.

Research grants to the medical school’s full-time and clinical faculty have ranked high among public medical schools. Faculty members also support the medical school with a percentage of fees raised in their clinical work.

Funding aside, there have been other remarkable changes that will shape the School of Medicine’s future. Portraits of the graduating classes reflect the first radical shift of the 21st century. The student faces in the photographs over the years go from nearly all men to an equal share of men and women.

An equal opportunity beginning

Among the most interesting tidbits of the School of Medicine’s history is that from its origin in the 1880s, school bylaws required that women be accepted for admission on an equal basis with men.

“It was a major accomplishment,” Shikes said. “Harvard didn’t admit women until 1945.”

Gender equity was also a dream that languished for reasons that still puzzle historians.

Nelly Mayo graduated in 1891 and became the School of Medicine’s first female alumnae. Portraits of early medical school classes show amazing diversity. Women and Latinos were well-represented among classes in the early 1900s.

But as Shikes correctly pointed out, diversity in a class of eight students is not hard to come by. Two women and one Latino in a class of eight provide remarkable breadth, at least on a percentage basis.

The actual number of women and minorities stayed relatively fixed as class sizes grew.

“Maybe society was such that women didn’t want to be doctors,” Shikes surmised. “Or maybe the admissions process was stacked against them (regardless of what the bylaws said).”

For whatever reasons, gender balance among the medical school’s modern classes is striking.

“The change,” said Shikes, “is just spectacular.” Women often outnumbered men in current graduating classes.

Eisenhower Suite

See photos of the rooms where President Dwight Eisenhower recovered from a heart attack while visiting Denver. Visitors can also sign up for tour of the suite.