ONE YEAR IN THE FUTURE OF MEDICINE

Abraham Nussbaum’s book explains CU’s new way to train physicians

By Tayler Shaw

October 2024

When Abraham Nussbaum, MD, sat down in Denver Health’s basement café to meet with Jennifer Adams, MD, to discuss a unique, patient-centered approach to training future doctors, he had no idea the conversation would eventually lead to a years-long journey of writing his latest book: “Progress Notes: One Year in the Future of Medicine.”

Nussbaum, a professor of psychiatry and assistant dean of graduate medical education at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, is the chief education officer at Denver Health. He was reviewing all the Denver Health education programs when Adams told him about the program she was leading, called a longitudinal integrated clerkship.

Under this program, Adams typically oversaw fewer than a dozen medical students who were trained differently from others by spending a year following the same set of patients and accompanying them to their medical appointments. It’s a training method that research has shown creates more empathetic doctors.

“Adams stood out to me as someone who had this plan and the data to show this approach worked. It made me think a lot about what was the same and different from my own medical training,” Nussbaum says. “I was struck that she was able to teach students not only how the body works, but also about the community.”

Abraham Nussbaum, MD,

Abraham Nussbaum, MD,Nussbaum asked Adams if he could follow a group of her students as they went through the longitudinal integrated clerkship, to which she agreed. For five years, he followed Adams and fellow educators as they recruited, selected, trained, and eventually graduated a cohort of medical students.

In his book, Nussbaum shares the journeys of seven students who went through the program, capturing the patient interactions that shaped them, the challenges they faced, and their aspirations to improve the quality of care patients receive. He also explains how the traditional model of medical training was formed, and the complex challenges the health care system faces.

What Nussbaum didn’t realize was that he was capturing the moments leading up to a monumental change for the CU School of Medicine. In 2021, the school adopted a new curriculum in which the longitudinal integrated clerkship became the standard training model for all medical students, making CU among the first large medical institutions in the country to use this model for all students.

“There are several issues that face medical care. Many will tell you it’s too complex, too costly, and too difficult to access,” Nussbaum says. “For me, I wanted to write about something that works.”

UPDATING THE CLERKSHIP MODEL

Jennifer Adams, MD

Adams, the assistant dean of medical education for the CU School of Medicine and a professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine, formed the Denver Health longitudinal integrated clerkship program in 2014.

“I had been practicing at Denver Health for about a decade as a primary care physician, and I’d been involved in medical education for a long time there,” she says. “I was approached by the curriculum leadership about the idea of a longitudinal integrated clerkship, which I’d never heard of before.”

Adams began researching the model, finding that most of these clerkships were in rural communities in the United States, Australia, and Canada. What stood out most to her was literature that showed how it benefitted students, such as higher measures of empathy and patient-centeredness, stronger mentorship, and equal, if not better, academic performances.

“I got excited and decided to take it on and develop the pilot program at Denver Health,” she says.

Under the traditional model of medical training, students followed block rotations of different core specialties during their third year of medical school. This could look like doing eight weeks of working in internal medicine, eight weeks of surgery, four weeks in pediatrics, and so on.

In a longitudinal integrated clerkship, rather than rotating through specialties, students are placed with a specific preceptor — meaning a practicing physician who provides training to the student — in all their core specialties for an entire year.

“They spend less time on a given week with each preceptor, so they may see their internal medicine or their surgery preceptor only once a week, but they continue that pattern all year long,” Adams says.

SELECTING PATIENTS TO FOLLOW

While some longitudinal integrated clerkship programs assign patients to students, Adams decided on a different approach. Instead, as medical students get to know their preceptors and their preceptors’ patients, each student chooses 15 patients to follow for the year.

“For instance, if I am a student’s internal medicine preceptor and they decide to follow a patient of mine for the year, that student will accompany the patient to their medical visits. If my patient goes to the emergency room, my student will go see that patient in the emergency room. If they are admitted to the hospital, my student will visit them in the hospital. If they are discharged, then we will do a home visit,” Adams says.

“It reflects real life. Patients don't live in internal medicine. They live a broad and engaged life, and this model has students learn the patients’ experience and develop these deep connections,” she adds.

There are some requirements for the types of patients the students select, such as needing to have at least one patient with a mental health condition and a patient in obstetrics. Yet, there is enough flexibility for students to still tailor their patient panel to the population they most want to help.

For example, one student featured in Nussbaum’s book, Maggie Kriz (Kuusinen), was passionate about serving patients experiencing homelessness. That’s why one of the patients she chose to follow was a man roughly her same age with chronic osteomyelitis, an infection of the bone, who had been experiencing homelessness since he was about 16 years old. In the book, Kriz explains she chose him because she wanted to help “guide him through medicine’s impersonal bureaucracies.”

“I think it’s important for students to select their own patients because human connection is not something I can assign. It depends on who the student bonds with,” Adams says. “That increases their engagement with the curriculum, and it sparks their excitement about learning.”

WRITING ‘PROGRESS NOTES’

When Nussbaum asked Adams if he could follow her and her students in the longitudinal integrated clerkship program at Denver Health, part of the reason she said yes was because she hoped to share the benefits of the training model.

“Abraham wanted this book to speak more to a general audience so they could understand the magic and power of what we’re doing here, and how that will transform care for patients and communities through education,” Adams says.

Nussbaum and Adams told students about the project before they applied for the program. Once the students began the program in 2017, Nussbaum took several different approaches to capturing their experiences. He joined lectures, conducted one-on-one interviews, and followed some students on their clinical service, capturing their interactions with patients.

“None of the patients’ real names are used, but we did represent the encounters with the patients in the book,” he says. “I tried to see a diversity of experiences the students went through.”

BENEFITING STUDENTS AND PATIENTS

From witnessing wedding announcements to clinical appointments, Nussbaum’s book reflects on the complexities of medical training and early adulthood. He even describes the students’ virtual graduation in 2020 and some of the challenges they faced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

He also highlights the ways the longitudinal integrated clerkship benefited both the students and their patients. Under the traditional training model, Nussbaum explains that doctors were often taught to think of only the “textbook of the body,” where sick patients are seen as bodies to be treated instead of as complex people.

The longitudinal integrated clerkship, on the other hand, also teaches the “textbook of the community,” giving medical students the time and space to get to know their patients — how they live, who they love, and the social determinants of health that impact them.

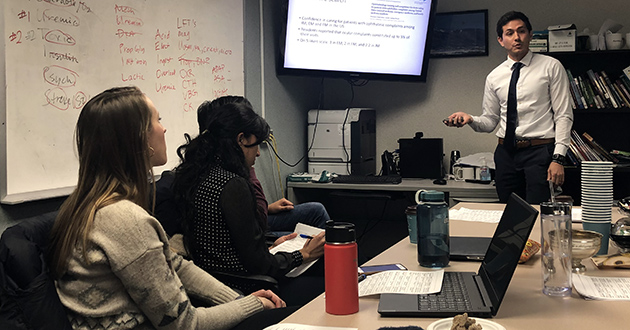

Maggie Kriz (Kuusinen) leading a seminar discussion. She chose a man experiencing homelessness as one of her patients because she want to help “guide him through medicine’s impersonal bureaucracies.”

Adams says the textbook of the community is critical to the longitudinal integrated clerkship.

“When I think about the type of medical school I want to be a part of, I think about social accountability. What does our community need in terms of health care? And what responsibility do we have, as medical educators, to create physicians who can rise to meet that need?” Adams says.

“When we are teaching students anatomy or pharmacology, that’s the textbook of the body — the traditional textbook. But that has to be in the context of what those human beings need. If it’s in a vacuum, then our students would be ill-equipped to practice in a socially accountable way,” she continues.

Throughout the year, Nussbaum witnessed patients develop trust with the medical students. For example, he describes an interaction one student, Itzam Marin, had with a female patient, where the patient kept referring to Marin as her doctor. Despite Marin correcting the patient and reminding her that he is still a student, the patient disagreed, saying she felt that Marin was more her doctor than a lot of other doctors.

It is a sentiment Adams has seen in her own research on the effectiveness of the longitudinal integrated clerkship. One research report found patients deeply valued the therapeutic alliances they built with the students, leading to improved patient experience, mitigation of perceived health system failures, and subjective improvement in health outcomes.

“At Denver Health, we interviewed patients about their experiences with these students and heard phenomenal descriptions of the impact the students had,” Adams says. “Our students really thrive in their connection with patients, and they flourish in their own professional development, personal journey, and connection with faculty.”

PRODUCING BETTER DOCTORS

Around 2017, when the CU School of Medicine began reassessing its curriculum, Adams took the opportunity to pitch expanding the longitudinal integrated clerkship to all medical students.

“When we really looked at the literature, it's clear — this model produced better doctors,” Adams says. “We presented that data to school leaders, showing we can achieve equal if not better academic outcomes and that our doctors would be more patient-centered and empathetic.”

Shanta Zimmer, MD, the senior associate dean for education, said the curriculum change aimed to find the best ways to train physicians to be community leaders who feel a sense of ownership in the health of their patients.

“The data we reviewed showed that this model is the absolute best way to create the types of doctors we want to create,” she says. “This was one of the most data-driven decisions we made in the new curriculum.”

Itzam Marin leading a seminar discussion when he was a medical student. During his clerkship, one of his patients insisted on calling him her doctor because of the connection they developed during her care. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Adams.

Itzam Marin leading a seminar discussion when he was a medical student. During his clerkship, one of his patients insisted on calling him her doctor because of the connection they developed during her care. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Adams.Zimmer says the data showed this model results in doctors who are more compassionate, patient-centered, community-centered, and still perform as well — or even better — than the other model. She believes this approach is what medical students dream of when they envision becoming a doctor, as they can form meaningful relationships with patients early on.

“I want everybody who graduates from the CU School of Medicine to be somebody who earns the trust of their patients and their families. And I think this model helps us to produce — and preserve — that type of person,” Zimmer says. “I’m really proud of the work Jen has done to create this model and to work to implement it across the entire school.”

Today, the CU School of Medicine has 16 longitudinal integrated clerkship programs at sites across Colorado. Students are matched to programs based on their preferences, such as those interested in pediatrics being placed at Children’s Hospital Colorado.

“It’s interesting to read the book now and reflect back on where we started,” Adams says. “It’s gratifying to realize that we stayed true to those roots and the importance of patient-centered education and connection to the community.

“We continue to maintain those positive outcomes we originally saw with the pilot program,” she adds. “We are now going into our third year of this new curriculum, and we’re seeing the same positive outcomes.”

When people read his book, Nussbaum hopes they recognize the sacrifices people who go into medicine make and the value of changing medical education so it benefits all people.

“All of us either are, or will become, patients someday,” Nussbaum says. “We need to have a medical practice that teaches about how to care for the body and the community.”