Roll Models

Horan Family Gives CU Medical Students a Lesson in Life

By Mark Couch

(April 2019) Each year, first-year medical students at the CU School of Medicine are

treated to an extraordinary lesson of courage and compassion by a family

with three sons who have Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

(April 2019) Each year, first-year medical students at the CU School of Medicine are

treated to an extraordinary lesson of courage and compassion by a family

with three sons who have Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

The Horans – parents Brian and Kimberly and sons Ryan, Aaron, and Ian – have been leading a class discussion in the Molecules to Medicine course for the past 13 years where they provide insight and a patient perspective not found in textbooks, lectures, or online.

The family offers a lesson on how to live.

Their session with students isn’t about some theory on disease progression. It isn’t a case study on how to make a diagnosis. It is a course on how to care.

The Horans show how physicians and aspiring physicians and anyone really should care for one another. Every day. All the time. They give an always honest, sometimes funny, occasionally bracing, look at life and how to live it.

Brian Horan always tells the class: “No question is off limits.”

Their way is practical and inspirational and grateful. Their advice to the students stems from their initial experiences with CU School of Medicine faculty who provided care to their family at Children’s Hospital Colorado.

“Ryan was diagnosed in 1992,” Kimberly said. “He was playing soccer at that time and we noticed that he couldn’t run or climb, run around the same way that other kids did. His kindergarten teacher also observed some physical challenges in him that she didn’t see in other kids.”

After testing Ryan, Richard Finkel, MD, a neurologist who was with CU and Children’s at that time, shared the news with Brian and Kimberly.

“He was just phenomenal,” Kimberly said. “Ryan was the only one with us at that time. He had Ryan go out in the hallway to play with the nurses. And I thought that was kind strange because he then shut the door and sat down and grabbed my hand and he grabbed Brian’s hand and said, ‘How’s your marriage? Because this is hard and it’s really going to be stressful.’”

Finkel’s personal touch – a 20-minute heartfelt conversation – set a tone for the care the family would receive for decades. It still inspires the family and serves as the model that they recommend to the medical students.

“We’ve seen more doctors than most do in their lifetime - fivefold,” Brian said. “And we’ve had plenty of good experiences and plenty of bad experiences and if we want things to get better not only for us but for the people behind us, then you’ve got to take an active role.”

The inspiration for coming to the classroom came after one of the neurologists treating the Horan boys asked Brian and Kimberly to meet with another family.

“He had met a family that also had the same thing, three sons with disabilities,” Kimberly said. “That family was really struggling with dealing with it, so he invited us to dinner with this other couple. We basically took over the whole evening, talking about what to expect.”

That neurologist, Brian Tseng, MD, PhD, happened to be a member of the School of Medicine faculty and he saw an opportunity to personalize a basic science course that is fundamental to medical training.

“Our course is heavily science-based and it is easy for students to feel far removed from the clinical world of patients amongst the facts and concepts about how basic genetics and biology works,” said Matt Taylor, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and director of adult clinical genetics in the Department of Medicine.

It’s the experience of human interactions that are illuminated by the patient visits to the classroom. Over the eight-week coursework, faculty bring in patients for sessions that make those connections.

“The Horans are a remarkable family and each year share their meaningful story and their perseverance with our students,” Taylor said. “In addition to showing our students the human side of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the Horans help our students think about cost of care, barriers to care, the good and less good elements of our medical system, how to behave professionally and compassionately to patients, and how to try to strive to do the right thing for patients.”

A significant experience the family discusses with the medical students relates to a life-or-death experience for oldest son, Ryan, when he was in his 20s. Despite the diagnosis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a genetic disorder that causes progressive weakness and atrophy in muscles, the family has always sought ways to remain as active as possible.

In this case, the family had gone skiing in Winter Park and Ryan was concerned about crashing.

“He’s always been a professional worrier,” Brian said. “But he worried himself enough to where he stressed his system and that allowed something to attack him.”

At dinner at the YMCA of the Rockies, where they were staying, Ryan was incoherent. At a nearby clinic in Granby, Ryan was in pulmonary distress. He was flown by helicopter to a Denver area hospital, but not to Children’s, which had been his lifelong medical home.

As Ryan’s condition worsened over the next few days, one of the physicians providing care was less-than-vigorous in offering hope and comfort. In fact, he advised the family give up.

“The doctor came in, worked for a while and then came up to me and said do you know what Ryan’s wishes are?” Brian said. “I was like, ‘What do you mean by his wishes?’ He said, ‘I mean his living will and stuff.’ I said myself and his mom usually take care of that. He said, ‘Well, we need to consider that and he walked out of the room.’”

Brian followed him out of the room.

“He said, ‘I don’t think we have any options,” Brian recalled. “I knew he wasn’t right and I knew in my heart. And even the nurse that was taking care of Ryan, she turned away when she heard the doctor say that.”

A pulmonary therapist helped stabilize Ryan and over the next three weeks he recovered. The experience still crackles as the Horans tell the story. “He gave up on our son and that should never happen,” Brian said.

Time and again, the Horans have shown that they don’t give up.

“Try not to let the disease dictate your life,” said Ryan. “It’s not a death sentence. You can live your life any way you want. Be positive.”

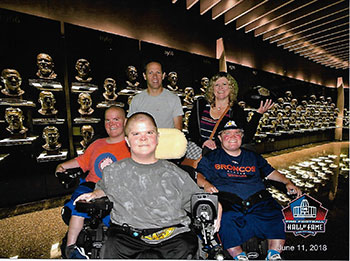

The Horans describe cruise ship vacations and cross-country treks to see the NFL Hall of Fame, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Ford’s Theatre, and the Statue of Liberty. They talk about summer trips to Lake Powell to spend time on their houseboat.

They talk about life transitions, like when Brian, an auto service manager, and Kimberly, a nurse, traded places to stay at home with their sons. Kimberly was home when they were younger. Now Brian stays home with them.

They discuss how Brian went back to college at the same time as the boys, about installing an elevator in their house, about setting off Fourth of July fireworks in the neighborhood, about attending sporting events, including sitting rinkside at a Colorado Avalanche game.

They are dedicated sports fans – “Actually we watch any sport that’s on television,” said Aaron. All three boys served as team managers in high school. An ESPN alert buzzed during the interview for this article.

They explain how they mentor others with muscular dystrophy, about how they set up a “Band of Brothers” to meet for meals and beer. “I think we are role models to a degree,” said Ian.

In the course sessions, the Horan sons said medical students often reserve their best questions for the lunch session after class. “No questions surprise us,” said Ian. “We’re open books.”

The Horans may offer their advice in the words and interactions in classes, but they are teaching by example.

“It’s difficult to live with, but you can live with it,” Ian said. “There are so many worse disease you can have. If you think about other people – everyone has their challenges – but they conquer it differently. This disease isn’t as bad as some out there.”

Kimberly’s message: “Don’t hold anything back. There’s so much to be gained from sharing your story. We’ve done it for years, not only with CU, but in other capacities as well. I think that you shouldn’t be afraid to share your story because I think there’s something to be gained and learned from your experience.”