Virtual Human Project Provides Digital Anatomies to Study

Body Donor Susan Potter featured in National Geographic magazine

(April 2019) When Victor Spitzer, PhD, director of the Center for

Human Simulation at the

University of Colorado School

of Medicine, talks about his

friend Susan Potter, he recalls a

“persistent” woman.

(April 2019) When Victor Spitzer, PhD, director of the Center for

Human Simulation at the

University of Colorado School

of Medicine, talks about his

friend Susan Potter, he recalls a

“persistent” woman.

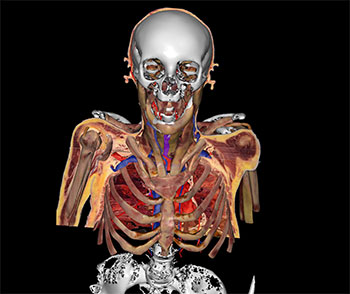

She volunteered again and again to donate her body to the Visible Human Project, an effort to create digitized anatomically detailed, three-dimensional representations of human bodies from cadavers that are sliced into microscopically thin layers.

Potter asked and asked and then she asked again. She refused to take no for an answer.

“I didn’t want to become her friend; I wasn’t particularly happy about imaging and sectioning my friend,” Spitzer said. “I knew her back when she sold flowers in front of the chancellor’s office on the Ninth Avenue campus every Christmas. She did a lot of things to support the medical school. This was her last wish to support it as best she could, in donating her body.”

When Spitzer finally acquiesced to her request, Potter then pushed for even more. She wanted him to show her the large freezer where cadavers are stored. She also insisted on inspecting the equipment Spitzer used to grind cadavers into slices barely the width of a human hair.

Now, four years after Potter died at age 87 in February 2015, she persists as more than a memory: She’s been frozen, sectioned and sliced. She exists in 27,000 photos taken of her entire anatomy, which are being reassembled gradually in high-resolution digital form.

Inside the Fitzsimons Building on the Anschutz Medical Campus, Spitzer works in his laboratory where the walls around the freezer are decorated with painted roses, done by two students in the School of Medicine’s master’s program in Modern Human Anatomy.

Potter had been known as the “flower lady” when the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center was located at the Ninth Avenue and Colorado Boulevard and she requested flowers be kept near Spitzer’s freezer, a place she felt needed more color and cheer.

“I would think Susan is smiling because she ended up where she wanted,” Spitzer said. “She wanted to end up in the students’ minds.”

Early in their education, CU medical students are introduced to the cadaver process and hear from people who want to donate their bodies. Potter herself spoke to students, and several of them ended up following her life as they moved into their professional careers.

“Susan has passed, but the last two years she has continued to talk to our students through video recordings saying why she’s donating, how she’s trying to help them and the whole health care profession,” Spitzer said. “So, she’s already in front of our medical students, just not her anatomy. Next year, they’ll see some of her anatomy, and every year they’ll see more of her anatomy.”

In the video recordings of her life, they’ll also see how passionate she was about improving the understanding of the human body. “She told people she would be in a freezer,” Spitzer said. “She agreed — but not at first — to being on the internet for the entire world to learn from her. She mainly wanted to be a donation to help the students at CU.”

Potter had read a newspaper article about the Visible Human Project some 25 years ago. A CU team led by Spitzer and David G. Whitlock, MD, PhD, had sectioned, from head to toe, a male and a female cadaver, using a calibrated machine to grind off layers as small as one-third of a millimeter. Each layer of the body was then photographed. Spitzer’s team, supported by the National Library of Medicine, took thousands of photos and then organized the data to allow users to interactively tour a virtual human body.

With Potter’s body, another will be available for a worldwide audience.

Potter’s story is especially remarkable because National Geographic assigned a photographer and writer to chronicle her journey. Originally, in 2004, the magazine’s staff expected a one-year assignment. Potter had been in a serious car accident, was suffering significant pain, and was mostly confined to a wheelchair. She expected to die within a year.

“National Geographic came on board to document her life for the next year,” Spitzer said, “and, in fact, continued on for the next 14 years.”

Technology has improved since the Visible Human Project originated in 1993, so much more detail will be seen in the virtual anatomy created from Potter’s body. The original Visible Human was ground into sections of 1,000 microns for the male (300 microns for the female); Potter’s body was ground off 63 microns at a time, resulting in thousands more photographs being taken. For comparison, a human hair is about 75 microns. Spitzer’s lab ultimately aims to expand beyond photos. Through his company, Touch of Life Technologies, located in the Fitzsimons Innovation Community, a hub that offers opportunities to develop commercial enterprises from academic activities on the Anschutz Medical Campus, he is developing ways to fabricate the feeling of living tissue.

“There’s no reason for us to keep a virtual cadaver,” he said. “We need to bring her back to life, to develop a living cadaver, one that you can see move or move in response to what you ask her to do. Being able to feel and touch and see is something very doable today.”

Identifying the entirety in Potter’s body is an enormous task, but assembling the images is a just small part of the overall project. When she is fully visualized, along with the material documented by National Geographic, medical students will be able to sift through her anatomical data, while also getting a picture of her psyche.

Potter’s personal history is a bit of a mystery. She didn’t talk much about her childhood, only that she grew up in Germany under difficult circumstances. As an adult, she was plagued by health issues, confined to a wheelchair, but always looking for some way to give to the CU School of Medicine. “We care about everything,” Spitzer said. “We want to correlate the anatomical with her feelings and her behavior, which is more the social sciences.”

Support from the School of Medicine and its Department of Cell and Developmental Biology and his company have allowed Spitzer to create the visualizations of Potter’s body. Spitzer’s goal, though, is even more ambitious and many more body donations are needed to fulfill it.

“We need to look at the anatomy of the virtual world as close as we do in the real world,” he said. “Someday, we need a bookshelf of bodies, or virtual human anatomy, from the very young throughout the aging process,” including people of all ethnicities.