Cataloging an Ancient Burial Site in Northwest Italy

Student Voice

By Rocio Belen Griggs

(April 2019) Hairy, windy roads tuck the town of Erli behind

the ear of the Neva Valley in the region of Liguria in northwest Italy,

where I spent my

first summer as a student in the Master of Science in Modern Human

Anatomy (MSMHA) program at CU Anschutz.

(April 2019) Hairy, windy roads tuck the town of Erli behind

the ear of the Neva Valley in the region of Liguria in northwest Italy,

where I spent my

first summer as a student in the Master of Science in Modern Human

Anatomy (MSMHA) program at CU Anschutz.

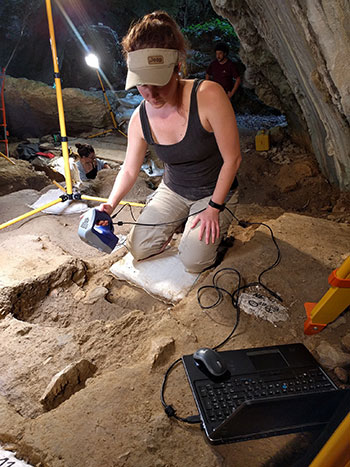

I was immersed in northwestern Italian culture and working at the archaeological field site of Arma Veirana, 3D scanning the remnants of an Upper Paleolithic human burial.

The infant frontal bone fragment was light and delicate in my hand, but weighed heavy in heart and mind alike. Thought to be 11,000 years old, the tooth enamel caps without roots and the absence of long bone epiphyses hint that the infant was under three months old. The skeletal remains were recovered in the cave adorned with decorative shell pendants, shell beads, and surrounded by lithics (stone tools). It was clear that the infant was well loved.

The work at Arma Veirana, directed by paleoanthropologists Jamie Hodgkins, PhD, CU Denver Anthropology, and Caley Orr, PhD, CU School of Medicine and MSMHA faculty, and their international collaborators has recovered evidence of Neanderthal occupation dating older than 50,000 years ago, as well as more recent Homo sapiens from the Upper Paleolithic period.

Now, as one of only a handful of Paleolithic sites in Europe that preserve infant remains, Arma Veirana holds great significance because it illustrates ritualistic burial practices among the last populations of hunter-gatherers on the continent, prior to the advent of farming and more sedentary lifestyles.

As an MSMHA student, I was invited to join the archaeological team to help create the 3D catalog of burial artifacts using the Artec Space Spider 3D Scanner.

At Arma Veirana, the crew uses innovative technologies to record the artifacts and human remains. Digital surveying equipment logs the exact coordinates of every artifact in situ. Photogrammetry has been used to compile thousands of photos into one cohesive 3D image of the entire site. And finally, 3D scans of the artifacts themselves are taken once removed from the ground.

In that effort, I became intimately familiar with the Space Spider, a portable, high-resolution 3D scanner. This scanner is equipped with three cameras, one texture camera, one regular flash, and six blue-light LEDs, which together can render a 3D geometrical model with a point cloud accurate to one hundredth of a millimeter, overlaid with texture resolution as accurate as one tenth of a millimeter.

Using these scans, we hope to create an open database of our findings that allows material to be studied from afar. Italian law prohibits artifacts from leaving the country under most circumstances. The accuracy of the technology has even allowed us to document the presence of ochre, a decorative pigmented substance tying these artifacts to ancient cultural practices. It has also facilitated the production of 3D printed replicas for study in the lab and to provide a tangible representation of the data the team hopes to publish soon.

Much remains to be learned about the Arma Veirana infant burial. We are awaiting DNA results from the bones and other artifacts, higher resolution radiocarbon dates, and analyses of the culturally significant pendants and beads, as well as a full digital reconstruction of the partially crushed cranium. This and other work at Arma Veirana will provide important information about the archaic and early modern human inhabitants of southern Europe.

Ultimately, this will contribute to a better understanding of our origins and evolution as a species. Participating on the Arma Veirana team was a thrilling experience and I am honored to represent the MS Modern Human Anatomy program and the greater community of CU Anschutz.

Rocío Belén Griggs is a graduate student in the School of Medicine’s MS Modern Human Anatomy Class of 2020 and vice president of diversity on the CU Anschutz Student Senate.

.