Leadership, Curiosity, Commitment

Leadership, Curiosity, Commitment

School of Medicine updates curriculum for medical students

By Mark Couch

(May 2020) A good medical education is the journey of a lifetime.

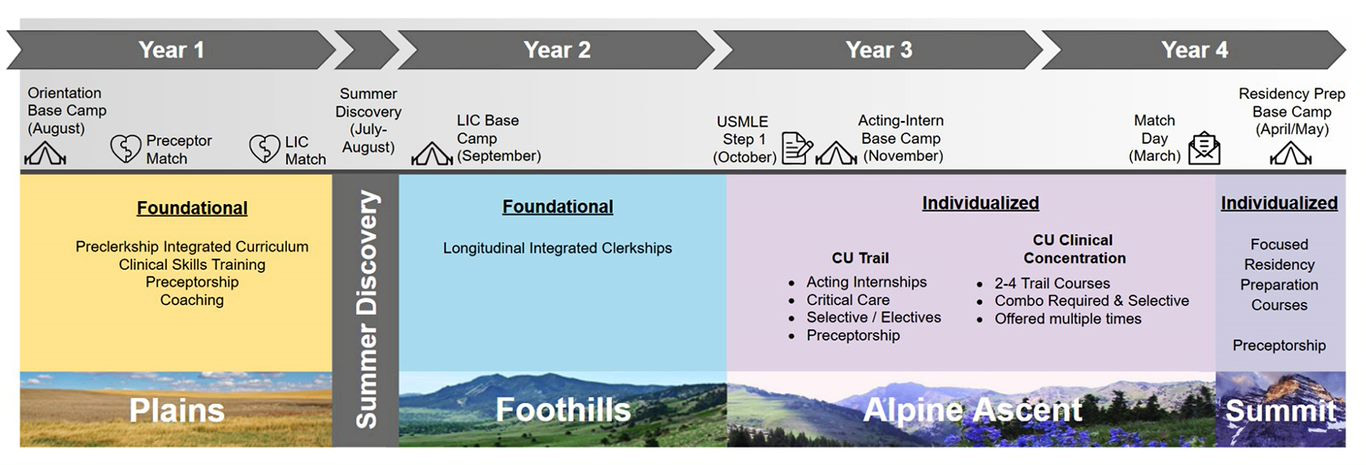

Beginning in 2021, medical students at the University of Colorado will embark on “The Trek,” a redesigned curriculum that aims to strengthen the connections student make as they learn to become physicians.

Those connections – between science and care, between provider and patient, between mentor and trainee – are intended to instill the knowledge and skills that students need to become accomplished physician-leaders while cultivating the personal characteristics that will contribute to ongoing success throughout their careers.

“If you look around our campus and at medicine from a big perspective, the way we deliver care is rapidly transforming,” said Shanta Zimmer, MD, senior associate dean for education and professor of medicine. “The way we approach the science of medicine is also rapidly transforming.”

And as a result, the way we teach medicine needs to transform, Zimmer said. The programming for a medical school education will still require the fundamentals. There will be no skipping anatomy. Students still need to know how to do a physical exam. But there will be an emphasis on learning in a new way.

For example, students will continue to study foundational science during their first year, but advanced understanding of basic sciences will be connected later in the learning process so that it is linked more directly to clinical experiences.

That is just one part of the redesigned curriculum known as the Trek.

“The students named it,” Zimmer said. “We had a contest. Michigan has the branches and the tree. UCSF has the bridges curriculum, which is kind of cool. A lot of places have done that in order to mark the transition or the launch of something new and innovative. So we went to our students and said, ‘What do you want this to be called?’”

The Trek

That first year of the Trek, which includes foundational science and clinical skills training, is akin to crossing the Plains.

Naming the program wasn’t the students’ only role. Students joined faculty, staff, and community leaders in helping craft the redesigned curriculum. Eighty-three students wrote essays explaining why they wanted to participate.

The curriculum update effort began in October 2017 with a kick-off retreat on campus that called on the medical school community to dream big and work hard on a project that will have significant impact on the future of the School.

“I told them to do a blue-sky approach, but it had to be on this planet,” Zimmer said. “That was the only restriction.”

Twenty-five committees were formed, involving more than 200 people, to review best practices and curriculum reform efforts at other medical schools, and to evaluate CU’s current program.

When the School of Medicine’s accrediting body in 2017 completed its thorough analysis, there were no citations related to educational programming. So why change it? The process of updating the curriculum is an important exercise in maintaining relevance as the demands of providing care grow and the methods of teaching and learning change.

While some subjects related to medical education are constant, the context is constantly changing. As a result, it’s necessary to pose questions about how the health care system works, about society and its impact on health, about how technology can improve the quality of care.

Zimmer listed a series of questions shaping how medical educators approach the task of teaching the next generation of physicians: “Is it going to be value-based care? Are we going to have a single-payer system one day? What does that look like from a technology perspective? Where does AI fit in? What about telemedicine and telehealth? Then there are the big data components. ... I think it makes good sense that as science and health care delivery are changing, we’re going to have to change medical education.”

If you ask again tomorrow about what questions should be asked, the questions will certainly change. The goal is to train physicians to be ready to address those changes and to continue to learn long after they’ve left school.

“I’ve started talking to applicants about coming into a school that has a curriculum revision process like the one we have going on, and what I’ve told them is, ‘Don’t come here if you don’t want to learn how to learn and you’re not going to be flexible with the things that you are learning,’” Zimmer said. “If something new happens in terms of CAR-T cells for treatment of leukemias or breast cancer down the line, then you’re going to have to learn about that as a practicing physician. You aren’t going to be able to say, ‘They didn’t teach that to me in medical school so I’m not going to care about it.’

“We’re creating people who like to learn all the time rather than creating people who have a set of knowledge. And I am happy that the Dean has given us the latitude to say that’s what we want to do and that’s why curiosity is one of the major pillars of the new curriculum.”

Leadership, Curiosity, and Commitment

The guideposts for the Trek curriculum are Leadership, Curiosity, and Commitment. Those are the values that all medical students should bring and strengthen as they earn their degree.

“Leadership was the one the Dean felt very strongly about because interdisciplinary teams are the way of medicine now,” Zimmer said.

Working together with other providers has been crucial component of medical education on the Anschutz Medical Campus for many years, thanks to interprofessional education programming and through a specialty track known as LEADS (Leadership Education Advocacy Development Scholarship).

Now, rather than have leadership as a focus of a track for some medical students, the redesigned curriculum will emphasize leadership throughout the learning process for every medical student.

“Business schools know how to train around leadership, the military knows how to train around leadership, even in law schools they have courses around leadership,” Zimmer said, “and in medicine, we’ve just kind of said, ‘Well, you’re going to be a leader,’ but we don’t do anything specifically to train you. So we’re going to be more deliberate about the importance of that.”

Commitment recognizes that being a physician requires persistence and passion, resilience and resourcefulness. To succeed, there will be times that personal sacrifices are necessary.

Longitudinal integrated clerkships

Such values are often learned by example, so medical students will be taught by strong, positive role models – clinicians, investigators, advocates – in longitudinal relationships. They will also do clinical training in longitudinal integrated clerkships, where they participate in comprehensive care of patients over time, engage in continuity relationships with preceptors and evaluators, and meet core clinical competencies across multiple disciplines simultaneously.

“I think that before we started this process that’s one of the most controversial decisions that we were going to make, which was how

are we going to teach students ‘the doctoring part’ that you think about in a medical school,” Zimmer said.

Longitudinal integrated clerkships, or LICs, are an ideal way to teach because it allows for mentoring relationships between faculty and students, ongoing connections between students and patients, and peer partnerships between small groups of students.

The School of Medicine has experience with LICs at Denver Health, at the School’s branch in Colorado Springs, and in rural settings and the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center. This spring, the School is launching a LIC in northern Colorado that will be based at the School’s branch in Fort Collins that is opening in partnership with Colorado State University.

The reason for pursuing a curriculum focused on LICs is the results they get. According to the School’s data, students in the LICs do as well as or better than their peers in the Match, on their rotations, in their residency programs, based on feedback from program directors, and on licensing exams.

“If you were to read the literature about LICs nationally, that’s true,” Zimmer said. “It also leaves students with a higher sense of compassion and commitment. If I am going to have the opportunity to do something that’s evidence-based to change our curriculum, this is the one that has the most evidence behind it in terms of making sense.”

In Trek-speak, the LICs are when the students travel through the Foothills of their educational journey. The experience remains foundational and is required before they can ascend to the individualized training that comes next in the Alpine Ascent. At the end of their fourth year, with elevated skills and knowledge, students will be ready for the Summit, which are individualized focused residency preparation courses.

With that hard-won perspective, the curriculum redesign team expects that students will be equipped to address the needs of patients and their communities in a new way. Rather than teach medical students a hospital-centric health systems approach, they hope new physicians will be looking for ways to provide the kind of care that the patients want to see.

“Patients are people, not a system” Zimmer said. “They like their schools, their places of work, their communities, their parks, their environment, and wouldn’t it nice to have our students right out of the gate focus on patients not where they’re sick, but where they’re healthy.

“Our curriculum is going to be taught from the systems that the community values, and that’s where you learn problem-solving, evidence-based medicine, patient-centered care, and you can learn that through the system of the community.

Feature Stories

- Building Professional Resilience Through Creative Arts

- Model Hearts and Virtual Reality

- Improving Care for Colorado; CU School of Medicine expands access to care statewide

- New Clinic is ‘Bigger than What’s in These Four Walls’

- Innovative Palliative Care Fellowship Program

- Leadership, Curiosity, Commitment; School of Medicine updates curriculum for medical students

- Student Voice: The Gift of Gratitude

- Faculty Matters: What Every Doctor Should Know About the Holocaust

Profiles

- Searching For Cures to Lung Diseases

- Osseointegration surgery offers hope for better, faster, stronger life

- Building a Team, Not Just a Building; Hospital leader receives life-saving care after stroke at work