Joined at the Heart

A Friendship between a Patient and CU Doctor

By Dan Meyers

(May 2, 2011) On a sparkling Colorado day a year ago, Nicole Bond took the stage to receive her college diploma. Bond graduated summa cum laude from the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

(May 2, 2011) On a sparkling Colorado day a year ago, Nicole Bond took the stage to receive her college diploma. Bond graduated summa cum laude from the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

In the audience at commencement, Marilyn Manco-Johnson watched Bond and cried.

Manco-Johnson, a physician who specializes in pediatric hemophilia, first saw Nicole Bond 22 years earlier at

"Did I think she would survive?" Manco-Johnson pauses several seconds before continuing. "No."

Over the next two-plus decades, Nicole endured medical crisis after crisis. Her father Scott was in the Army, and he and her mother Dawn moved all over the country. Yet Manco- Johnson remained Nicole’s medical lifeline.

And out of that intense medical

Nobody questions that friendship. But it raises an important topic: Where should each side in the health care equation draw boundaries? A doctor-patient relationship, of course, can go too far, raising ethical issues. But studies demonstrate that patients benefit when their doctor knows them well.

At a medical school, how do you talk about that?

The University of Colorado School of Medicine addresses this in classrooms and hospitals.

Professionalism is a key part of CU’s foundations of doctoring

"It’s a long conversation," says Jackie Glover,

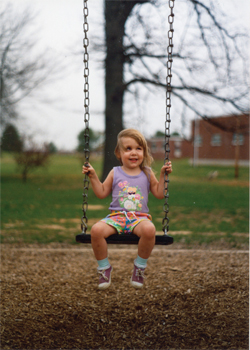

At first, it didn’t seem like Nicole would have the chance to be anyone’s friend

At first, it didn’t seem like Nicole would have the chance to be anyone’s friend

"By five hours after her birth," Dawn says, "I knew she had

It was great luck that the military facility had a pediatric hematologist on

"The first doctor we met with in Colorado said Nicki should never have been treated," Dawn recalls. "He said she would have a horrible, prolonged death. We were despondent. We spent a long time holding our daughter."

The doctor did suggest they consult with Manco-Johnson. Nicole was transferred to University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), where Manco-Johnson first set eyes on the terribly sick child. Manco-Johnson told the parents she would try.

In those days, it wasn’t clear how to prevent severe clots in newborns. Manco-Johnson tried the drug Coumadin, which had never been given to a patient that young. She’d take a 1 mg. pill, crush it, put it in a syringe and drip it into Nicole’s throat. It wasn’t easy for Nicole, then or since. She has been a frequent visitor to UCH and The Children’s Hospital as her treatment evolved and new issues cropped up.

Lesions on Nicole’s legs would announce a new clotting episode. She was treated with fresh frozen plasma but developed an allergic reaction. She was given activated protein C, but when that stopped, her skin blotched purple with purpura. For years Dawn carried Nicole’s medical information to prove she hadn’t abused her daughter. Now Nicole is on doses of concentrated protein C and Coumadin. She’s more or less stable.

Manco-Johnson says only 13 people in North America have survived this severe condition.

Nicole Bond is one of them.

"Dr. Manco Johnson saved Nicole’s life," Dawn Bond says.

Nicole’s first memories of treatment are of dread

Nicole’s first memories of treatment are of dread

She associated the smell and sounds of the doctor’s office with the poking and prodding she endured. But she also remembers a soothing voice, first in the office and later on the telephone. Manco-Johnson would talk with her, ask questions, listen to the answers.

And then, in a coffee shop in the Seattle airport, Nicole felt the relationship with her doctor shift. Manco-Johnson, between planes, met with the family. Nicole showed her a book she and her fourth-grade class had written called "Seeing Differently," about visually impaired students. Manco-Johnson read a bit of it, began asking about it.

"She seemed to understand the importance of this to me," Nicole says. "Before, there wasn’t much time to talk about anything else [beyond medical care]. This time we were really interacting."

And Manco-Johnson? From early on, she just liked the kid.

"She has a unique sense of herself," Manco- Johnson says of Nicole. "She likes to use formal language, to dress formally. She never felt compelled to fit in. She has no negativity or fear about what she can do. She wants to live in Paris. She wants to be an editor. She’s such an independent person, friendly, curious, very engaged."

The doctor was there for late-night sweet and sour chicken in Nicole’s hospital room before a surgery, which Manco-Johnson attended at Nicole’s request. She joined the family for pasta and Dawn’s slow-cooked sauce at Ronald McDonald House, and for tea at Denver’s Brown Palace hotel for Nicole’s 14th birthday party. When Bond’s younger sister Kristin was born, Manco-Johnson was there in case her expertise was needed. But she also thought to bring a gift, a toy piano, for Nicole.

What about those doctor-patient boundaries?

Friendship can’t trump medical care, Manco- Johnson says.

Friendship can’t trump medical care, Manco- Johnson says.

"But at the same time, I never have a strict feeling that I have to separate from the patients I feel friendship for," she adds. "When I got the invitation to go to Nicole’s graduation it was wonderful. I knew immediately I was going to be there."

Nicole has read about the doctor-patient issue. Sure, there is a line, she says, "but that line should be as blurry as possible."

And so last year a doctor came to the college graduation of a young woman whose life she had saved.

After the tears during the ceremony, the doctor stood with three generations of the girl’s family as they posed for pictures. And in those photos, no one is smiling more broadly than Marilyn Manco-Johnson and Nicole Bond.

Dear Third-

Year Student

Graduating medical students write letters of hope and advice to incoming third-years in the annual Letters to a Third-Year Student.