Contact UCHealth

Stomach Cancer

Clinical Trials

Make a Gift

What Is Stomach (Gastric) Cancer?

Stomach cancer, also called gastric cancer, begins when cells in the stomach begin growing out of control.

The stomach, an organ located on the left side of the abdomen, is a part of the digestive tract that helps digest food. The food enters the stomach through the esophagus where it is then broken down by the stomach muscles. It then leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine, passing on to the large intestine.

Stomach cancer can happen in any part of the stomach, and in most of the world stomach cancer begins in the main part of the stomach, called the stomach body. In the United States, however, stomach cancer is more likely to begin at the gastroesophageal junction, or the area where the esophagus joins the stomach.

Stomach cancer tends to develop slowly over the course of many years. Before cancer develops, pre-cancerous changes may happen in the inner lining of the stomach, called the mucosa. Unfortunately, these pre-cancer changes rarely cause symptoms, so they often are undetected.

Where stomach cancer begins in the stomach is important because different areas can cause different initial symptoms. For example, stomach cancer that begins at the gastroesophageal junction is often treated similarly to how esophageal cancer is treated, because the symptoms can be similar.

Stomach Cancer Prognosis and Survival Rates

Stomach cancer is most commonly diagnosed in people past middle age. The average age of diagnosis in the United States is 68 and about six of every 10 people diagnosed each year are 65 or older. In 2023, the American Cancer Society estimated 26,500 cases of stomach cancer cases are estimated to be diagnosed; 15,930 in men and 10,570 in women. An estimated 11,130 deaths are estimated to be caused by stomach cancer in 2023; about 6,690 men and 4,440 women.

In Colorado, there are an estimated 360 new cases and 150 deaths from stomach cancer each year.

Stomach cancer accounts for about 1.5% of all new cancers diagnosed in the United States. Encouragingly, over the past 10 years the number of stomach cancers diagnosed has decreased by about 1.5% each year.

In the first decades of the 20th century, stomach cancer was the leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, but today isn’t in the top 15 most common causes of cancer deaths. The reasons for this decline aren’t totally understood, but two significant factors are the increased use of refrigeration in food storage, leading to decreased consumption of salted and smoked foods (which are stomach cancer risk factors); and the decline in Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacterial infections, which is considered a significant cause of stomach cancer.

Despite the decrease of stomach cancer cases in the United States, it still is common in other parts of the world, particularly east Asia.

Stomach cancer prognosis depends on the stage of the cancer when it’s diagnosed and a person’s overall health at the time of diagnosis. Because stomach cancer is often advanced when it’s diagnosed, it can be treated but is not frequently cured.

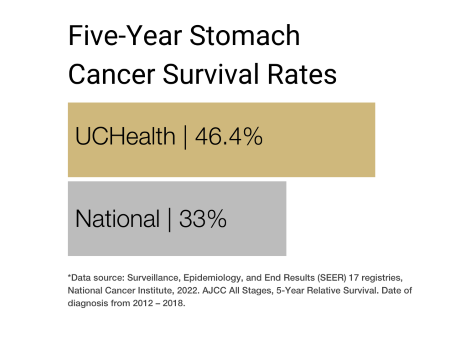

Stomach cancer survival rates often are expressed in terms of five-year relative survival, which is the percentage of people with the same type and stage of stomach cancer who are alive five years after their diagnosis, compared with people in the overall population. So, the five-year relative survival rate for stomach cancer is 36%, which means that overall, people diagnosed with stomach cancer are 36% as likely as similar people who do not have stomach cancer to be alive 5 years after diagnosis.

However, each person is different and response to treatment can vary widely. Clinicians and researchers at the University of Colorado Cancer Center, along with their colleagues around the world, are continually working toward new treatments, such as minimally invasive surgery and developing new anti-cancer drugs to help patients achieve better quality of life and better outcomes.

Why Come to CU Cancer Center for Stomach Cancer

The University of Colorado Cancer Center is the only National Cancer Institute (NCI) Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in Colorado and one of four in the Rocky Mountain region. Our doctors provide world-class, patient-centered care and have access to cutting-edge treatments not available at most other medical centers in the country.

The Katy O. and Paul M. Rady Esophageal and Gastric Center of Excellence started in Late 2022. This group is committed to providing the best possible care to all its patients, initiating new research, as well as investigating new clinical trials. The center works with the University of Colorado Cancer Center and across the institution, including UCHealth.

The weekly Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic brings together a team of expert surgeons, gastroenterologists, pathologists, oncologists, radiologists, and more focused on the esophagus and stomach. Together, the team analyzes a patient’s diagnosis and recommends a specific treatment plan for the individual by the end of the visit. The Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic has a designated point of contact, for prospective patients, current patients, and referring physicians. Contact the Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic at 720-848-0405.

Shared Content Block:

Cancer Center Styles -- Give headings inside accordions and tabs more top margin

Types of Stomach Cancer

The type of stomach cancer you have is based on the type of cell where your cancer began. Examples of stomach cancer types include:

- Adenocarcinoma stomach cancer begins in mucus-producing cells. This is the most common type of stomach cancer. Nearly all cancers that start in the stomach are adenocarcinoma stomach cancers. There are two subtypes of Adenocarcinoma stomach cancer, Gastric cardia cancer begins in the top inch of the stomach, and non-cardia gastric cancer is cancer that begins in all other sections of the stomach.

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) starts in special nerve cells that are found in the wall of the stomach and other digestive organs. GIST is a type of soft tissue sarcoma.

- Gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (GEJ) is a cancer that forms in the area where the esophagus meets the gastric cardia. GEJ may be treated similarly to stomach cancer or esophageal cancer.

- Lymphoma is a cancer that starts in immune system cells. The body's immune system fights germs. Lymphoma can sometimes start in the stomach if the body sends immune system cells to the stomach. This might happen if the body is trying to fight off an infection. Most lymphomas that start in the stomach are a type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- Carcinoid tumors or Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors are cancers that start in the neuroendocrine cells. Neuroendocrine cells are found in many places in the body. They do some nerve cell functions and some of the work of cells that make hormones. Carcinoid tumors are a type of neuroendocrine tumor.

- CDH1 – some mutations in the CDH1 gene increase your lifetime risk for developing diffuse stomach cancer in addition to other inherited tumors such as breast cancer. This mutation is diagnosed through genetic testing and there is often strong family history of stomach cancer. For patients with a CDH1 mutation, prophylactic gastrectomy is recommended between ages 18 and 40.

Risk Factors for Stomach Cancer

Clinicians and researchers have found several risk factors that make a person more likely to get stomach cancer, including:

- Sex – men are more likely to get stomach cancer than women.

- Age – while younger people can get stomach cancer, risk increases with age; the majority of people with stomach cancer are diagnosed in their 60s, 70s, and 80s.

- Ethnicity – stomach cancer in the United States is more common in people who are Black, Hispanic, Native American, Pacific Islander, or of Asian descent.

- Geography – stomach cancer is more common in east Asia, eastern Europe, central America, and South America.

- Helicobacter pylori infection – scientists have learned that Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) bacteria is a significant cause of stomach cancer, especially cancers in the lower part of the stomach. People diagnosed with stomach cancer have higher rates of H pylori infection than those without stomach cancer; the bacteria is also associated with certain types of lymphoma of the stomach. However, most people who carry this bacteria never develop stomach cancer.

- Being overweight or obese – these factors are associated with an increased risk for stomach cancers of the upper part of the stomach.

- Diet – diets that include significant amounts of food preserved with salt, such as pickled vegetables and salted meat and fish, are associated with increased stomach cancer risk. Also, regular consumption of processed, grilled, or charcoaled meats is associated with an increased risk of certain stomach cancers. Diets with low or no fruits and vegetables increase stomach cancer risk, while eating lots of fresh fruits, particularly citrus, and raw vegetables has been shown to lower stomach cancer risk.

- Alcohol use – people who consume three or more drinks per day have been shown to have increased stomach cancer risk.

- Tobacco use – stomach cancer risk is significantly higher in people who smoke.

- Previous stomach surgery – People who have had part of their stomachs removed to treat non-cancerous diseases, such as ulcers, are at increased risk for stomach cancer. Scientists suggest this is because the stomach is less acidic following surgery, allowing harmful bacteria to be present in the stomach. In this scenario, stomach cancer typically develops many years after the surgery.

- A family history of stomach cancer.

- Certain occupations – research has shown that people who work or have worked in the metal, coal, or rubber industries experience higher rates of stomach cancer.

- Certain stomach polyps – while most polyps do not increase a person’s stomach cancer risk, adenomatous polyps, or adenomas, can sometimes develop into stomach cancer.

- Inherited cancer syndromes – some inherited gene mutations can lead to conditions that increase stomach cancer risk, including hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, Lynch syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, gastric adenoma, and proximal polyposis of the stomach, Li-Fraumeni syndrome and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

- Having type A blood.

Symptoms of Stomach Cancer

Because screening for stomach cancer is not routine in the United States, stomach cancer often isn’t found until it has grown large or spread outside the stomach. Further, in its early stages, stomach cancer rarely causes symptoms. However, when stomach cancer symptoms occur, they can include:

- Weight loss without trying.

- Trouble swallowing.

- Loss of appetite.

- Abdominal pain.

- Feeling full after eating just a small meal.

- Heartburn or indigestion.

- Nausea.

- Vague abdominal discomfort, generally above the navel.

- Vomiting, with or without blood.

- Fatigue or feeling tired or weak, which can be a result of anemia.

However, most of these symptoms are most commonly caused by something other than stomach cancer, including an ulcer or viral infection, so it’s important to consult with a medical care provider about these symptoms.

Diagnosing Stomach Cancer

Stomach cancer usually is found when a person consults a physician about one or several signs and symptoms of the disease. If stomach cancer is suspected, exams and tests may be used to determine whether a person has stomach cancer. These can include:

A medical history, physical exam, and tests to look for bleeding, during which a health care provider may ask about certain risk factors and symptoms of stomach cancer. A physical exam may include feeling the belly for anything abnormal. A doctor might also order blood tests to screen for anemia, or low red blood cell count, which could be caused by cancer bleeding into the stomach. A stool test might also be ordered to look for blood, even if it’s not visible to the naked eye.

Upper endoscopy, during which a physician passes a thin, flexible lighted tube with a camera at the end – a device called an endoscope – down a patient’s throat. This helps the physician see the lining of the esophagus and stomach, as well as the first part of the small intestine. If anything abnormal is seen, biopsy samples may be taken with instruments passed through the endoscope. The samples drawn in a biopsy are examined in a lab for cancer cells.

Biopsy, which may be ordered if something abnormal is spotted during an endoscopy or imaging test. During a biopsy, a doctor removed a small sample of the abnormal area for testing in a lab. Because some stomach cancers can start deep in the stomach lining, biopsy during an endoscopy may not be possible. If that is the case, a doctor may perform an endoscopic ultrasound to insert a thin, hollow needle into the stomach wall to draw a sample for testing.

Imaging tests, which may be ordered to help determine whether a suspicious area is cancer or, if cancer is present, to learn if it has spread. These tests may include:

- Upper gastrointestinal (GI) series – an x-ray test to look at the inner lining of the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the small intestine. This test is not used as frequently as an endoscopy because it may miss abnormal areas and doesn’t allow a physician to take biopsy samples, but it is less invasive than endoscopy and can be useful in certain situations.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan – a scan that uses x-rays to make detailed, cross-sectional images of the body’s soft tissues. CT scans are able to gain clear images of the stomach and can help confirm the location of cancer. They also can help guide needle biopsies in areas where cancer is suspected to have spread.

- Endoscopic ultrasound – a test used to determine how far cancer might have spread into the stomach wall or nearby lymph nodes. In this test, a small ultrasound probe is attached to the tip of an endoscope and passed down the throat and into the stomach.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan – a test to help determine the extent of cancer in the body. During this test, patients are injected with a slightly radioactive type of sugar, which collects in cancer cells and allows a special camera to take pictures of areas of radioactivity.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – a test that can show detailed images of the body’s soft tissue using radio waves and strong magnets. MRIs are not used as frequently as CT scans, but may be useful in situations where the cancer is suspected to have spread.

- Chest x-ray – a scan that can show whether cancer has spread to the lungs and whether a person has serious heart or lung disease, which might impact surgical options.

Laparoscopy, a surgical test that can help determine whether the cancer is still only in the stomach and not spread to other parts of the body. During a laparoscopy, which is performed under general anesthesia in an operating room, a thin, flexible tube with a small video camera at the end is inserted through a small cut in the belly. Using the video camera, a doctor can look at the surfaces of the organs in the abdomen and nearby lymph nodes. They also can remove tissue samples for biopsy.

Stages of Stomach Cancer

Stomach cancer staging helps determine whether and how far the cancer has grown in the stomach, and whether it has spread to areas outside the stomach. Staging not only describes the extent of stomach cancer in the body, but helps guide how best to treat the cancer. Staging also is used to describe relative survival rates.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM system is most commonly used to stage stomach cancer, except those that start at or have grown into the gastroesophageal junction. Those particular cancers are staged similarly to esophageal cancer.The TNM system describes the extent of the primary tumor, including whether and how far it has grown into the layers of the stomach wall; whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes; and whether it has metastasized to other parts of the body.

Treatments for Stomach Cancer

At the University of Colorado Cancer Center, stomach cancer is treated by a multidisciplinary team that usually includes a medical oncologist, a surgical oncologist, a gastroenterologist, a radiation oncologist, and a nutritionist. The team may also include nurses, physician assistants, psychologists, social workers, financial specialists, rehabilitation specialists, and others. The multidisciplinary team may provide two or more types of treatment as well as provide patients with information about participating in clinical trials, if available. Health care providers also will work with patients to determine goals for treatment, as well as discuss complementary or alternative treatments.

Surgery for stomach cancer

Surgery is a common part of stomach cancer treatment plans and, in conjunction with other treatments, can help a patient achieve no evidence of disease status if the cancer hasn’t spread to other parts of the body. Surgery for stomach cancer may aim to remove cancer or to provide palliative care by preventing the stomach from being blocked by the tumor or preventing the tumor from bleeding.

Surgery to remove the cancer may include:

- Endoscopic resection, which may be used to treat early-stage cancers that haven’t grown deeply into the stomach wall. This surgery doesn’t require an incision; rather, the surgeon passes a flexible endoscope down the throat and into the stomach. Tools can be passed through the endoscope, enabling the surgeon to remove the tumor and some layers of the stomach wall around it.

- Partial gastrectomy, in which part of the stomach is removed. Sometimes part of the esophagus or part of the small intestine may also be removed, depending on where in the stomach the cancer originated.

- Total gastrectomy, during which the entire stomach is removed if the cancer has spread widely through it. Nearby lymph nodes and the omentum, a layer of fatty tissue that aprons the stomach and intestines, are also removed. If the cancer has spread to the spleen or parts of nearby organs, those parts may be removed as well. After the stomach is removed, the esophagus is attached to the small intestine, allowing small amounts of food to pass through.

- Minimally invasive surgery: The surgeons at the University of Colorado are experts in minimally invasive cancer surgery. When possible, surgeons may be able to use smaller incisions and instruments (laparoscopic or robotic) to perform the operation.

Palliative surgery for stomach cancer may include:

- Gastric bypass, which is commonly used in instances when the stomach cancer begins in the lower part of the stomach. A surgeon attaches part of the small intestine to the upper part of the stomach, which lets food leave the stomach.

- Subtotal gastrectomy, in which the part of the stomach containing the tumor is removed to help with bleeding, pain, or the tumor blocking food from passing through. Because the goal isn’t to cure the cancer, nearby lymph nodes generally are not removed.

- Feeding tube placement, which is an option for people who aren’t able to eat or drink enough to get adequate nutrition. A feeding tube may be placed through the skin of the abdomen and into the lower part of the stomach or into the small intestine, allowing liquid nutrition to be poured directly into the tube.

- Tumor Cytoreduction and Heated Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC), in selected patients with limited tumor spread inside the abdomen, surgeons may be able to remove the visible tumor and treat the abdomen directly in the operating room with heated chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy for stomach cancer

Chemotherapy may be used as a stomach cancer treatment at different times. It can be administered before surgery with the aim of shrinking the tumor to make surgery easier. For some stages of stomach cancer, it is a standard treatment option.

Chemotherapy may also be administered following surgery to remove the tumor. A goal of chemotherapy administered at this time is to kill any cancer that may have been too small to remove during surgery. It can help prevent cancer from returning and is often administered in conjunction with radiation therapy.

If the stomach cancer has spread to other parts of the body, chemotherapy is often the main treatment and may be given in cycles, with periods of rest in between to allow the body to recover. Individual cycles usually last several weeks.

Radiation therapy for stomach cancer

Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays or particles to kill cancer in targeted parts of the body. In some early-stage stomach cancers, radiation therapy is often used along with chemotherapy before surgery to shrink the tumor, making it easier to remove.

Radiation therapy may also be used along with chemotherapy after surgery to kill can remaining cancer cells that weren’t removed during surgery. This can help prevent cancer from recurring or slow its spread. Radiation therapy may also be used to treat stomach cancers that can be removed with surgery, helping ease symptoms like bleeding, pain, or eating difficulties.

Targeted drug therapy for stomach cancer

Ongoing research has shown that drugs targeting changes in stomach cancer cells may work differently than standard chemotherapy, or in ways that chemotherapy can’t. Targeted therapy drugs may also be used along with chemotherapy.

Some targeted therapies may target HER2, a growth-promoting protein sometimes found in stomach cancer cells. Other drugs have been developed to target VEGF, a protein that instructs cells to make new blood vessels, which is a problem when those cells are tumor cells. A very small percentage of stomach cancers show changes in NTRK genes, so TRK inhibitor drugs may be used.

Immunotherapy for stomach cancer

Immunotherapies use certain medicines to boost a patient’s own immune system to fight cancer. An important type of immunotherapy for treating stomach cancer is immune checkpoint inhibitors. These immunotherapy drugs target “checkpoint” proteins on immune cells that must be turned on or off to initiate an immune response against cancer cells. Sometimes cancer can appropriate these checkpoints to avoid being attacked by a body’s immune system, so immune checkpoint inhibitors help prevent cancer from doing that.

Latest News from the Cancer Center

Loading items....

Information reviewed by Martin McCarter, MD in October 2023.