Contact UCHealth

Pancreatic Cancer

Clinical Trials

Make a Gift

What Is Pancreatic Cancer?

The pancreas is a gland that sits behind the stomach and in front of the spine. It serves two major functions in the body: the exocrine component makes proteins called enzymes that are released into the small intestine to help the body digest food and the endocrine component makes hormones, including insulin — the substance that helps control the amount of sugar in the blood. The endocrine component also makes somatostatin, glucagon, pancreatic polypeptide (PP), and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), each of which plays an important role in regulating metabolism.

Pancreatic cancer occurs when mutations develop in the cells of the pancreas, causing the cells to multiply rapidly. These cells can form a tumor that destroys normal body tissues and structures.

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 66,440 new cases of pancreatic cancer are diagnosed in the U.S. each year, resulting in approximately 51,750 deaths. In Colorado, there are approximately 1,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer diagnosed each year.

Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death in both men and women and is expected to become the second leading cause of cancer death within in the next decade.

Pancreatic Cancer Survival Rates and Prognosis

Pancreatic cancer prognosis depends on the type of cancer and the stage at which it is diagnosed. Although pancreatic cancer accounts for only 3% of all cancers in the United States, it leads to about 7% of all cancer deaths.

The five-year survival rate for patients with localized pancreatic cancer where the tumor is still confined to the pancreas is 44%. Approximately 12% of all pancreatic cancers are discovered at this stage.

Pancreatic cancer survival rate decreases as the cancer spreads beyond the immediate area of the pancreas. The five-year survival rate for patients with regional pancreatic cancer (where the cancer has spread to nearby structures or lymph nodes), is about 16%, and 36% of cases are diagnosed at this point.

The survival rate for patients with distant pancreatic cancer (where the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body such as the lungs, liver, or bones) is 3%. This accounts for about 52% of all diagnoses.

Why Come to CU Anschutz Cancer Center for Pancreatic Cancer

As the only National Cancer Institute Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in the state of Colorado and one of only four in the Rocky Mountain region, the University of Colorado Anschutz Cancer Center has doctors who provide patient-centered pancreatic cancer care and researchers dedicated to diagnostic and treatment innovations.

→ Veteran’s Pancreatic Cancer Caught ‘At Just the Right Time’

The CU Anschutz Cancer Center is home to the Pancreas and Biliary Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic, which offers patients an “all in one” approach to clinical care. At a multidisciplinary clinic, patients are evaluated in one day by specialists who treat this specific cancer, including world-class surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, gastroenterologists, nurse practitioners, and others, who then collaborate on care. This multidisciplinary approach has proven to be the new standard of care for pancreatic cancer.

Contact the Pancreas/Biliary Multidisciplinary Clinic at 720-848-8096.

The cancer center also has a Pancreas Surveillance Clinic for high-risk patients, those who need lifelong surveillance following surgery, and those who have pre-malignant pancreatic cysts.

Due to advanced surgical techniques, more effective medicines, and a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, the CU Anschutz Cancer Center is able to operate on 30% or more of pancreatic cancer patients, which is nearly double the national average. This distinction, along with proven excellence in pancreatic cancer prevention, education, care, and outcomes, lead to the CU Anschutz Cancer Center being named a National Pancreas Foundation Academic Center of Excellence for pancreatic cancer.

Learn more about this designation:

The CU Anschutz Cancer Center has developed techniques to remove pancreatic tumors that also involve the peri-pancreatic vessels (portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, hepatic artery, celiac trunk, and superior mesenteric artery). In certain cases, patients who are not considered candidates for surgery elsewhere because of a locally advanced disease may receive surgery here.

Patients who have been told that their pancreatic cancer is unresectable (unable to be removed through surgery) might want to contact the CU Anschutz Cancer Center for a second opinion. Our world-class surgeons may be able to resect a tumor that was classified as unresectable by other surgical oncologists. When possible, CU surgeons perform pancreatic procedures using minimally invasive surgical techniques, including laparoscopic or robotic surgeries.

There are numerous pancreatic cancer clinical trials being offered by cancer center members at any time. These trials offer patients options to traditional pancreatic cancer treatment and can result in remission or increased life spans.

CU Anschutz Cancer Center doctors also treat non-cancerous disorders of the pancreas, such as acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, and hereditary pancreatitis.

We also have one of the few dedicated pediatric pancreas centers in the country. Our experts specialize in the treating of pediatric pancreatic tumors and other inflammatory pancreatic diseases with a multidisciplinary approach. For more information, visit the Pediatric Pancreatic Surgery Program at our clinical partner, Children’s Hospital Colorado. We collaborate closely with our adult Pancreas Cancer Program at the University of Colorado Anschutz Cancer Center to gain the best multi-disciplinary pancreas cancer care and outcomes in the western United States.

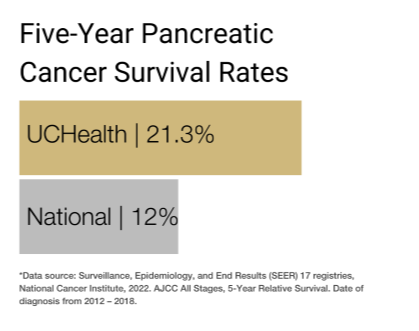

Our clinical partnership with UCHealth has produced survival rates higher than the state average for all stages of pancreatic cancer.

Types of Pancreatic Cancer

Different types of cells in the pancreas can become cancerous, and the type of cell affected determines the type of pancreatic cancer. These are categorized by looking at the cells under a microscope. Doctors use this information to understand the expected growth pattern and speed of the cancer and determine the best course of treatment.

About 93% of all pancreatic tumors develop in the exocrine component of the pancreas, while only 7% develop in the endocrine component.

Exocrine Pancreatic Cancers

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the most common type of pancreatic cancer, accounting for about 95% of cancers of the exocrine component. These tumors usually start in the ducts of the pancreas. This is called ductal adenocarcinoma. Less commonly, tumors can form in the acini, the small sacs on the end of the ducts. This is called acinar adenocarcinoma. They may also develop from the cells that manufacture enzymes, in which case they are called acinar cell carcinomas.

Rare types of exocrine cancer that together make up the other 5% of exocrine component pancreatic cancers include adenosquamous carcinomas, colloid carcinomas, hepatoid carcinomas, pancreatoblastomas, signet ring cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, undifferentiated carcinomas, and undifferentiated carcinomas with giant cells.

Endocrine Pancreatic Cancers

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) start in the endocrine cells of the pancreas. Also called islet cell tumors, NETs are less common than other pancreatic cancers but tend to have a better prognosis. NETs can be functioning or nonfunctioning based on whether they make hormones. A functioning NET is named for the hormone the cells normally make, such as insulinoma, gastrinoma, glucagonoma, somatostatinoma, PPomas, and VIPomas.

Similar and Related Cancers

Ampullary cancer starts in the ampulla of Vater, which is where the bile duct and pancreatic duct come together and empty into the small intestine. Ampullary cancer, also called carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater, isn’t technically pancreatic cancer, but it is treated in much the same way. The tumors often block the bile duct while they’re still small, causing bile to build up, which leads to yellowing of the skin and eyes (called jaundice). Because of this, ampullary cancer is usually found earlier than pancreatic cancer and often has a better prognosis.

Duodenal cancer is a rare form of cancer of the duodenum — the first and shortest part of the small intestine. When cancer cells begin to form in the duodenum, tumors can block food from passing through the digestive tract. Duodenal tumors may spread to the pancreas and treatment options (such as the Whipple procedure) are often similar.

Distal bile duct cancer starts in bile ducts, the series of thin tubes that go from the liver to the small intestine. Bile ducts move bile from the liver and gallbladder into the small intestine, which helps digest the fats in food. Distal bile duct tumors are found farthest down the bile duct, near the small intestine. The common bile duct passes through the pancreas before it joins with the pancreatic duct and empties into the duodenum at the ampulla of Vater.

Pre-cancerous Conditions That Can Lead to Pancreatic Cancer

Some cases of pancreatic cancer may begin as pre-cancerous conditions.

The CU Anschutz Cancer Center has a clinic dedicated to the management of cystic tumors of the pancreas. These tumors are common in the general population and are often discovered incidentally during a cross-sectional imaging procedure performed for non-pancreas related issues.

The detection of these tumors is very important. Although some are benign, others have the potential to progress to invasive cancer over time.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMN) are the most common of the cystic tumors of the pancreas. These neoplasms can progress from dysplasia to cancer over time.

There are two major categories of IPMNs. In one, called branch-duct IPMN, the disease involves only the peripheral ducts of the gland and appears as single or multiple cysts in the pancreas. Although this type of IPMN has a low risk for cancer progression, it is still possible. It is crucial that patients affected by this disease are included in a surveillance program. In case of radiological concerns during the follow-up, surgery can prevent cancer or treat it at an earlier stage.

When the disease involves the main pancreatic duct alone (main-duct IPMN) or a combination with the peripheral ducts (mixed-type IPMN), the risk of cancer increases significantly. A larger percentage of patients affected by main duct or mixed type IPMN require surgery. At the CU Anschutz Cancer Center, we offer these patients the possibility to do a “personalized resection” though the use of an intra-operative endoscope that allows us to define the extension of the disease in the pancreas.

Mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) are cystic tumors that can progress to cancer. These tumors occur mostly in women and are usually located in the body and/or tail of the pancreas. The removal of these tumors at the right time can prevent the cancer transformation.

Serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs) are, in contrast with mucinous cystic neoplasms, are almost always benign. The only indication for resection for these tumors is the presence of symptoms or local complications related to the growth.

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) are rare, slow-growing tumors that almost always develop in young women. These tumors can be malignant. The surgical treatment of SPNs is always indicated (when feasible), even in cases of locally advanced or metastatic disease.

Even though the biology of the cystic tumors of the pancreas can vary from tumor to tumor, their appearance is very similar in many cases. That means that it is often difficult to determine the type of tumor. This is why the management of these tumors should be done in high-volume and experienced centers like the CU Anschutz Cancer Center.

Pancreatic Cancer Causes and Risk Factors

Pancreatic cancer has multiple risk factors — conditions or behaviors that increase a person’s risk of developing the cancer.

History of cystic tumors of the pancreas: Some cystic tumors of the pancreas have the potential to progress to cancer or have been associated with an increased risk of cancer. These tumors need expert evaluation to be managed. The presence of a cyst in the pancreas should always trigger a consultation in a specialized pancreas center.

Smoking: Smokers are two to three times more likely to develop pancreatic cancer than non-smokers. In fact, about 25% of pancreatic cancers are thought to be caused by tobacco use. The risk of developing pancreatic cancer starts to drop after a person stops smoking.

Weight: People who are very overweight or obese are about 20% more likely to get pancreatic cancer. Carrying extra weight around the waistline may increase the risk of pancreatic cancer even in people who are not obese.

Diabetes: Pancreatic cancer is more common in people with diabetes, specifically those with type 2 diabetes. It is unclear whether people with type 1 diabetes (also called juvenile diabetes) also have a higher risk.

Chronic pancreatitis: This long-term inflammation of the pancreas is linked to an increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Chronic pancreatitis is often diagnosed in patients who smoke or exhibit heavy alcohol use.

Exposure to certain chemicals: Workers in industries that use certain types of chemicals — such as pesticides, benzene, certain dyes, and petrochemicals — may have a higher risk of pancreatic cancer. This is especially prevalent among people in the dry cleaning and metal working industries.

Age: The risk of pancreatic cancer increases with age. About two-thirds of people diagnosed with pancreatic cancer are 65 or older, and the average age of patients when they are diagnosed is 70.

Gender: Men have a slightly higher chance of developing pancreatic cancer than women. This may be due in part to higher tobacco use in men.

Race and ethnicity: Black people and people of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage are slightly more likely to develop pancreatic cancer than Asian, Hispanic, or white people.

Family history: Although most people who get pancreatic cancer do not have a family history of it, there is evidence that it may run in some families. Sometimes the higher incidence is due to an inherited syndrome. In other cases, the gene causing the increased risk is unknown.

Inherited gene mutations: Some inherited gene changes (mutations) can raise the risk of pancreatic cancer. Research suggests these gene changes may be responsible for up to 10% of all pancreatic cancer diagnoses. Some examples of genetic syndromes that can lead to pancreatic cancer include hereditary pancreatitis, usually caused by mutations in the PRSS1 gene; hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome, caused by mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes; familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome, caused by mutations in the p16/CDKN2A gene; Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer or HNPCC), usually caused by a defect in the MLH1 or MSH2 genes; Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, caused by defects in the STK11 gene; Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS); and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

Acquired gene mutations: Most gene mutations related to pancreatic cancer are acquired, rather than inherited. Some of these acquired gene mutations are linked to cancer-causing chemicals (like those found in tobacco smoke or certain industrial chemicals). However, many gene changes are random, with no external cause. Some sporadic cases of pancreatic cancer involve changes in the p16 and TP53 genes, which are also present in some inherited genetic syndromes. But many pancreatic cancers also involve changes in genes such as KRAS, BRAF, and DPC4 (SMAD4), which are not present in inherited genetic syndromes.

Diet: Some studies indicate that diets heavy in red and processed meats and saturated fats may raise the risk of pancreatic cancer. People who consume a lot of sugary drinks may also be at risk.

Physical inactivity: Some research suggests that a lack of exercise might increase a person’s risk of developing pancreatic cancer.

Alcohol: There may be a link between heavy alcohol use and pancreatic cancer. Heavy drinking can also lead to conditions such as chronic pancreatitis, which is known to increase the risk of pancreatic cancer.

Symptoms of Pancreatic Cancer

Doctors often describe pancreatic cancer as a “silent disease,” because early pancreatic cancers rarely cause symptoms. Because of this, pancreatic cancer is seldom detected at its early stages. However, the earlier pancreatic cancer is diagnosed and treated, the better the prognosis, so it’s important to understand the most common pancreatic cancer symptoms.

When the tumor is located in the pancreatic head, one of the primary symptoms of pancreatic cancer is jaundice, which is characterized by yellow skin and eyes, dark-colored urine, light-colored or greasy stools, and itchy skin. Jaundice is caused by a buildup of bilirubin, a substance made in the liver and found in bile. Normally, bile is released by the liver and travels through the bile duct into the intestines, where it helps break down fats. When the bile duct gets blocked, bile can’t reach the intestines, and the amount of bilirubin builds up.

Other symptoms of pancreatic cancer include:

- Pain in the upper back or abdomen.

- Burning feeling in the stomach.

- Bloating.

- Bowel obstruction.

- Floating stools with a particularly bad odor and an unusual color.

- Weakness and fatigue.

- Loss of appetite.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Chills and sweats.

- Fever.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Gallbladder or liver enlargement.

- Blood clots.

- New diagnosis of diabetes or existing diabetes that is becoming more difficult to control.

These symptoms can also be caused by other medical conditions, such as pancreatitis, ulcers, gallstones, hepatitis, mononucleosis, and other liver and bile duct diseases. Anyone experiencing these symptoms should check with a doctor to learn the cause.

Screening for Pancreatic Cancer

Screening may be used to look for pancreatic cancer before a person shows any symptoms of the disease. Although pancreatic cancer screening is not recommended for most people, some people with risk factors for the disease, especially those with a family history of pancreatic cancer, may choose to be screened.

In contrast, the presence of some of the cystic tumors of the pancreas is an indication for surveillance.

The most common pancreatic cancer screening methods are:

Genetic testing: Genetic testing looks for the gene changes that cause certain inherited conditions that increase pancreatic cancer risk. The tests look for these inherited conditions, not pancreatic cancer itself.

Imaging tests: The two most common tests used to try and detect early-stage pancreatic cancer are endoscopic ultrasounds and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

These tests may also be performed after a patient has reported pancreatic cancer symptoms as part of the diagnostic process or as part of the staging process for patients who have already been diagnosed.

Diagnosing Pancreatic Cancer

To diagnose pancreatic cancer, a doctor will start by asking about the patient’s medical and family history. Then, they will perform a physical exam. The doctor may examine the skin, tongue, and eyes to see if they are yellow — a sign of jaundice. They may also feel the abdomen for lumps, swelling, or abnormal buildup of fluid in the abdomen (ascites).

Based on their findings, the doctor may refer the patient to a specialist, such as a gastroenterologist, for additional tests and treatment. Gastroenterologists are doctors who specialize in diseases of the digestive system.

If the doctor or gastroenterologist suspects a patient may have pancreatic cancer, they will order more tests. These may include all or some of the following.

Imaging Tests for Pancreatic Cancer

Imaging tests can show where the tumors are located and whether they have spread from the pancreas to other parts of the body. They may also be used to monitor whether the cancer is growing and spreading. A radiologist is a doctor who specializes in interpreting imaging tests.

Some of the imaging tests used to diagnose pancreatic cancer include computed tomography (CT) scans, MRI scans, transabdominal ultrasounds, endoscopic ultrasounds, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), positron emission tomography (PET) scans or PET-CT scans, and angiography.

Blood Tests for Pancreatic Cancer

Doctors may perform different blood tests to help diagnose pancreatic cancer. These can include liver-function tests to check for abnormal levels of bilirubin and tumor-marker tests. Tumor markers are specific proteins found in the blood when a person has cancer. Tumor markers that may be helpful in diagnosing pancreatic cancer are carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA 19-9.

Biopsies for Pancreatic Cancer

Although imaging and blood tests may strongly suggest pancreatic cancer, the only definitive way to diagnose the disease is with a biopsy. This involves removing a small sample of the tumor and examining it under the microscope. There are a few different biopsies a doctor might use to look for pancreatic cancer.

An endoscopic biopsy is the most common biopsy for diagnosing pancreatic cancer. During this procedure, the doctor inserts an endoscope (a thin, flexible, tube with a small video camera attached to the end) down the throat and into the small intestine near the pancreas. Then, the doctor uses an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to guide a needle into the tumor or an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to brush cells from the bile or pancreatic ducts.

During most percutaneous biopsies, another biopsy option for diagnosing pancreatic cancer, the doctor inserts a thin, hollow needle through the skin of the abdomen and into the pancreas to remove a small piece of a tumor. The doctor uses images from ultrasounds or CT scans to guide the needle into place. This is called a fine needle aspiration (FNA). In some cases, the doctor may need to perform a core needle biopsy to collect a larger piece of tissue.

Doctors rarely use surgical biopsies to diagnose pancreatic cancer, but they may be performed in rare cases where the surgeon is concerned the cancer has spread beyond the pancreas to other organs in the abdomen. Most surgical biopsies for pancreatic cancer are laparoscopic, meaning the surgeon makes multiple small incisions rather than one large one (which is called a laparotomy).

A negative biopsy does not guarantee the absence of cancer. Therefore, a biopsy is not always necessary before an operation. However, biopsies are needed for pre-operative chemotherapy.

Genetic or Germline Testing for Pancreatic Cancer

Doctors may refer patients with pancreatic cancer to a genetic counselor to determine if they could benefit from genetic or germline testing, which involves testing a blood or saliva sample to look for DNA mutations (such as BRCA mutations) that may indicate a hereditary predisposition to cancer. This information can help guide future treatment decisions.

Staging Pancreatic Cancer

After confirming the presence of pancreatic cancer, the doctor will try to determine the stage of the disease, which is based on several factors, including the size of the tumor and whether it has spread outside the pancreas. The stage significantly impacts both the prognosis and treatment options.

Many of the same tests used to diagnose pancreatic cancer are also used to assign a stage, in addition to a surgical procedure called a staging laparoscopy, during which a surgeon makes a few small incisions in the abdomen and inserts a tiny video camera into the abdomen to look at the pancreas and other organs. This helps the surgeon see if the cancer has spread to other parts of the abdomen.

The staging system used most often for pancreatic cancer is the TNM system, which measures the size of the tumor (T-tumor) and whether it has grown outside the pancreas into nearby blood vessels; whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N-node) and, if so, how many; and whether the cancer has metastasized (M-metastasis) to distant lymph nodes, bones, and organs.

Using the TNM assessment, the doctor will assign an overall stage to the cancer from 0 (carcinoma in situ) to 4. In general, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread and the better the outlook for the patient.

Pancreatic Cancer Stages

Stage 0: The tumor is confined to the top layers of the pancreatic duct cells. It has not invaded deeper tissues or spread outside the pancreas. It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or distant parts of the body. These tumors are sometimes referred to as carcinoma in situ and are usually easy to remove.

Stage 1: The tumor is confined to the pancreas and is no larger than 4 cm across. It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or distant parts of the body.

Stage 2: The tumor may be larger than 4 cm across and may have spread to nearby lymph nodes (though no more than three). It has not spread to distant parts of the body.

Stage 3: The tumor may have grown beyond the pancreas and into nearby blood vessels. It may have spread to nearby lymph nodes, but it has not spread to distant parts of the body.

Stage 4: The cancer has metastasized to distant parts of the body, such as the liver, peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity), lungs, or bones. It can be any size and may have spread to nearby and distant lymph nodes.

The stages outlined above can be further broken down based on the size of the original tumor and the extent to which the cancer has spread.

Pancreatic Cancer Grades

In addition to stages, doctors will often describe pancreatic cancer by grade and by whether they are resectable (able to be removed surgically).

Pancreatic cancers are assigned grades ranging from 1 to 3 based on how the cancer cells look under a microscope. Grade 1 (G1) cancers look like healthy pancreas tissue and Grade 3 (G3) cancers look very abnormal. Low-grade cancers tend to grow and spread more slowly than high-grade cancers.

Invasive and Non-Invasive Pancreatic Cancer

For treatment purposes, surgeons may categorize pancreatic tumors based on whether they can be removed with surgery.

If the tumor is still confined to the pancreas (or has spread just beyond it) and the surgeon believes the entire tumor can be removed during surgery, it is called resectable.

If the tumor may have already reached nearby blood vessels but the surgeon believes it may still be removed completely with surgery, it is called borderline resectable. The patient may receive chemotherapy (and/or radiation therapy) before surgery. If the tumor has even more significant vascular involvement it is called locally advanced. The patient usually receives chemotherapy before surgical exploration is performed.

If the tumor cannot be removed with surgery, it is called unresectable.

Patients who have been told their pancreatic tumors are unresectable may want to seek a second opinion from a CU Anschutz Cancer Center doctor. We have world-class surgeons who may be able to offer surgical solutions that other surgeons cannot.

Treatments for Pancreatic Cancer

The treatment for pancreatic cancer is tailored to each patient and depends on the size of the tumors, the stage at which the patient is diagnosed, and the patient’s general health. Pancreatic cancer care teams may include numerous health care professionals, such as primary care physicians, gastroenterologists, surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, as well as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, dietitians, pain specialists, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and rehabilitation specialists.

Some of the primary treatments for pancreatic cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, targeted drug therapy, and immunotherapy. Many patients receive at least one or more of these treatments in combination. When pancreatic cancer is advanced the doctor may focus on symptom relief (palliative care) rather than curative treatments to keep the patient comfortable for as long as possible.

Some patients may also be eligible to participate in clinical trials — controlled research studies of new or experimental treatments or procedures.

Surgeries for Pancreatic Cancer

Surgery for pancreatic cancer involves removing all or part of the pancreas, depending on the location and size of the tumor. An area of healthy tissue around the tumor (called a margin) is usually also removed to make sure no cancer cells are left behind.

Not all pancreatic cancer patients are candidates for curative surgery, since most pancreatic cancers are found after the disease has already spread and the tumor is no longer resectable.

Different types of surgery may be performed depending on where the tumor is located in the pancreas. Curative surgery is done mainly to treat tumors in the head of the pancreas. Because these tumors are near the bile duct, they often cause jaundice, which sometimes allows them to be found early enough to be removed completely.

A Whipple procedure may be performed if the cancer is located only in the head of the pancreas. During this extensive type of surgery, the surgeon removes the head of the pancreas and part of the small intestine called the duodenum, as well as the extra hepatic bile duct, part of the stomach, and nearby lymph nodes. Afterward, the surgeon reconnects the digestive tract, pancreas, and biliary system.

A distal pancreatectomy may be performed if the tumor is located in the body or tail of the pancreas. During this surgery, the surgeon removes the tail and body of the pancreas, as well as the spleen (when needed) and nearby lymph nodes.

If the cancer has spread throughout the pancreas, the surgeon may perform a total pancreatectomy. This involves the removal of the entire pancreas, part of the small intestine, a portion of the stomach, the common bile duct, the gallbladder, the spleen, and nearby lymph nodes.

In some cases that involve the peri-pancreatic vessels, the pancreatic surgeons at CU Anschutz can also remove, unblock, and reconstruct these vessels during the same procedure, which is called a pancreatectomy associated with vascular resection and reconstruction. This kind of operation is performed in a few centers. Patients with vascular involvement from the tumor may want to consult our surgeons for a second opinion.

When possible, CU surgeons perform Whipple procedures and distal pancreatectomies using minimally invasive pancreatic surgical techniques, including laparoscopic or robotic surgeries.

Chemotherapy for Pancreatic Cancer

Chemotherapy uses drugs to destroy cancer cells. It may be used before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) to try to shrink the tumors so they can be removed more easily during surgery. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is also used to treat tumors that are too large to be removed by surgery. Chemo can also be used after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) to kill any cancer cells that have been left behind. Chemotherapy is often given in combination with radiation therapy, which is known as chemoradiation or chemoradiotherapy.

Chemo drugs for pancreatic cancer can be injected into a vein (IV) or taken by mouth as a pill. These drugs enter the bloodstream and reach almost all areas of the body, making this treatment potentially effective for cancers whether or not they have spread. Some of the most common chemotherapy drugs for pancreatic cancer are gemcitabine (Gemzar), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin (Eloxatin), albumin-bound paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane), capecitabine (Xeloda), cisplatin, irinotecan (Camptosar), nanoliposomal irinotecan (Onivyde), and Leucovorin (Wellcovorin). Patients may receive one chemotherapy drug or a combination of them.

Targeted Drug Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer

Targeted therapies use medications to inhibit the action of defective genes and slow or stop the growth and spread of pancreatic cancer cells while limiting harm to healthy cells.

Erlotinib (Tarceva) is a drug approved by the FDA for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Erlotinib targets a protein on cancer cells called epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) that helps the cancer grow and spread. For this reason, erlotinib is often referred to as an EGFR inhibitor. In patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, it is often given in combination with the chemotherapy drug gemcitabine.

Olaparib (Lynparza) is approved for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer associated with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. This type of drug is known as a PARP inhibitor. PARP enzymes are normally involved in a pathway that helps repair damaged DNA inside cells. By blocking the PARP pathway, olaparib makes it difficult for tumor cells with a mutated BRCA gene to repair damaged DNA, which often leads to their death. It is often used to treat patients who have been on platinum-based chemotherapy, such as oxaliplatin or cisplatin, for at least 16 weeks with no evidence of disease progression.

Larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) and entrectinib (Rozlytrek) can be used for any type of cancer — including pancreatic — that harbors a specific genetic change called an NTRK fusion. These NTRK inhibitors are most often used in cases of metastatic pancreatic cancer or locally advanced pancreatic cancer that has not responded to chemotherapy.

Immunotherapy for Pancreatic Cancer

Immunotherapy, also called biologic therapy, stimulates the patient's own immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells.

One of the most important characteristics of the immune system is its ability to recognize and avoid attacking the body's normal cells. To do this, it uses “checkpoint” proteins on immune cells. Cancer cells sometimes use these checkpoints to keep the immune system from attacking them. Drugs that target these checkpoints — called checkpoint inhibitors — can correct this.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is a checkpoint inhibitor that targets PD-1, a protein on immune system T cells that normally helps stop these cells from attacking normal cells. By blocking PD-1, this drug boosts the immune response against pancreatic cancer cells. These immune checkpoint inhibitors are most often used for patients whose pancreatic cancer cells have tested positive for specific gene changes, such as a high level of microsatellite instability (MSI-H) or changes in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes.

Radiation Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer

Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays (such as x-rays) to kill cancer cells. It may be used before surgery (neoadjuvant radiation) to shrink the tumor or after surgery (adjuvant radiation) to destroy any remaining cancer cells. Radiation is often given in combination with chemotherapy, which is known as chemoradiation or chemoradiotherapy.

External-beam radiation therapy is the primary type of radiation therapy used for treating pancreatic cancer and focuses radiation from a source outside of the body on the cancer.

Palliative Care for Pancreatic Cancer

Palliative care focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms during a serious illness. Although palliative care is often performed for patients whose cancer is considered untreatable to keep them comfortable, it is not synonymous with hospice care or end-of-life care. Any patient, regardless of age or stage of cancer, may receive this type of care, which is often used while undergoing aggressive treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

Radiation is sometimes used as palliative care to help relieve pancreatic cancer symptoms, as is palliative chemotherapy, which can lessen pain, improve a patient’s energy and appetite, and stop or slow weight loss.

Stent placement or bypass surgery may also be performed as palliative measures in cases where the tumor is blocking the common bile duct or small intestine.

During a stent placement, a small tube (the stent) made of plastic metal is put inside the bile duct or intestine to keep it open even if a nearby tumor is pressing on it. This is usually done through an endoscope (a long, flexible tube), but the stent can also be placed through the skin during a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). A bile duct stent can also help relieve jaundice before curative surgery, which can lower the risk of complications from surgery.

Bypass surgery is another option for relieving a blocked bile duct. During this procedure, the surgeon reroutes the flow of bile from the common bile duct directly into the small intestine, bypassing the pancreas. In other cases, a connection can be made between the stomach and a loop of bowel downstream from the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine), in order to bypass an obstruction. This is known as a gastric bypass and may be performed in cases where the cancer has the potential to grow large enough to block the duodenum, which can cause pain and vomiting and often requires urgent surgery. During either type of bypass surgery, the surgeon may also be able to cut some of the nerves around the pancreas or inject them with alcohol, which can reduce pain caused by the cancer.

A special diet, medications, and specially prescribed enzymes may help a patient digest food better if their pancreas is not working well or has been partially or entirely removed.

Some patients develop diabetes as a result of pancreatic cancer and its treatment. In these cases, the patient may need to start taking insulin. This is especially common after a total pancreatectomy.

Morphine-like drugs called opioid analgesics are often prescribed to help reduce pain. Pain specialists may also administer special nerve blocks, such as a celiac plexus block, which helps relieve abdominal or back pain. During a nerve block, the nerves are injected with an anesthetic to relieve pain for a short time or a medication that destroys the nerves entirely so that the pain cannot return.

Laura Foote's Pancreatic Cancer Journey

Latest in Pancreatic Cancer from the Cancer Center

Loading items....

Information reviewed by Benedetto Mungo, MD, in October 2025.