Contact UCHealth

Colorectal Cancer

Shared Content Block:

News feed -- crop images to square

Clinical Trials

Make a Gift

What Is Colorectal Cancer?

Colorectal cancer is a highly common cancer type that forms in the cells of the colon and rectum, which make up the large intestine or gastrointestinal tract, where liquid waste is converted into formed stool. Colorectal cancer is also known as colon cancer and rectal cancer; these are grouped together because of their common characteristics, symptoms, and treatments.

Colorectal cancers grow slowly, most commonly starting as growths, or polyps, on the tissue lining the colon or rectum. Some polyps can turn into cancer eventually, over time, but not all polyps become cancer.

Over time, polyps can grow into the wall of the colon or rectum, growing outward through the layers, and eventually growing into blood vessels or lymph vessels. The stage of colorectal cancer is determined by how deeply it penetrates the colon or rectum wall and if it has spread beyond the gastrointestinal tract.

According to the American Cancer Society, colorectal cancers are the third most common type of cancer in the United States. More than 152,810 people are diagnosed with colorectal cancer each year. In Colorado, there are an estimated 2,130 new cases of colorectal cancer each year.

Colorectal cancer is preventable and highly curable when diagnosed and treated early.

Why Come to CU Anschutz Cancer Center for Colorectal Cancer

CU Anschutz Cancer Center doctors offer patients a comprehensive evaluation of benign and cancerous conditions of the colon, rectum and anus. As the only National Cancer Institute Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in Colorado and only one of four in the Rocky Mountain region, we have doctors who provide top-notch, multidisciplinary, patient-centered care with improved outcomes. Our doctors are the only physicians in a 500-mile radius who are part of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) advisory panel. The NCCN establishes treatment guidelines that doctors all across the United States use as a reference.

There are over 100 colorectal cancer clinical trials currently being offered by cancer center members, giving patients many different treatment options. Whenever possible, our doctors look for ways to treat colorectal and anal conditions using the least invasive techniques that can accomplish the goal.

The Colorectal Multidisciplinary Clinic brings together a team of expert surgeons, gastroenterologists, pathologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and more to focus on problems affecting the colon, rectum and anus. Together, the team analyzes a patient’s diagnosis and recommends a specific treatment plan for the individual by the end of the visit.

Contact the Colorectal/HIPEC Multidisciplinary Clinic at 720-848-0714.

At the CU Anschutz Cancer Center, we have a dedicated treatment and research program for young adults with colorectal cancer. This program is important because young patients with colorectal cancer have unique issues, related to their cancer diagnosis and the impact of their cancer treatment.

According to the American Cancer Society, 12% of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer have a young onset (before age 50). Over 3,600 men and women younger than 50 die each year from colorectal cancer.

→ Recommended Colorectal Cancer Screening Age Lowered to 45 for People at Average Risk

Typically, routine screenings for colon and rectal cancer do not begin until age 45, which means key symptoms often go unrecognized. This could be one reason that young onset colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates are increasing, even as they decline for older adults.

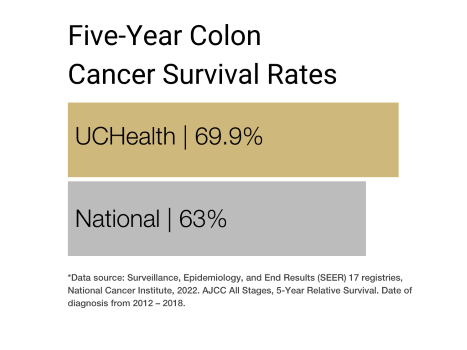

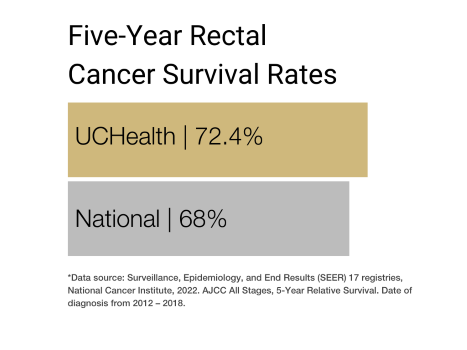

Our clinical partnership with UCHealth has produced survival rates higher than the state average for all stages of colon and rectum cancer.

Types of Colorectal Cancer

There are three different types of polyps that can form in the colon and rectum: adenomatous polyps (adenomas), hyperplastic polyps and inflammatory polyps, and sessile serrated polyps (SSP) and traditional serrated adenomas (TSA).

Adenomatous polyps (adenomas) are polyps that sometimes turn into cancer, which classifies them as a pre-cancerous condition. There are three types of adenomas: tubular, villous and tubulovillous.

Hyperplastic polyps and inflammatory polyps are the most common polyps and are generally not pre-cancerous.

Sessile serrated polyps (SSP) and traditional serrated adenomas (TSA) are often treated like adenomas because they have a higher risk of forming colorectal cancer.

Most colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas that begin as adenomas. These cancers start in the cells that make mucus to lubricate the inside of the colon and rectum.

Other types of rare tumors that start in the colon and rectum include carcinoid tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), lymphomas and sarcomas.

Carcinoid tumors form from cells in the lining of the intestine.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) start in cells called the interstitial cells of Cajal in the wall of the colon.

Lymphomas most commonly start in the lymph nodes but can also start in the colon, rectum or other organs.

Sarcomas can form in the blood vessels, muscle or connective tissues on the wall of the colon and rectum.

Causes of Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is caused by DNA changes or mutations that occur within healthy cells. Normal cells in the body go through a life cycle where they grow and divide to form new cells and then die when the body no longer needs them. Cells contain DNA that tells the cell what to do. When a cell’s DNA is damaged, cells continue to grow and divide where they aren’t needed by the body. This buildup of cells becomes a tumor.

Risk Factors for Colorectal Cancer

There are several factors that might increase the chance of developing colorectal cancer. These risk factors include:

Age: Colorectal cancer can be diagnosed at any age, but the majority of people are diagnosed after age 50. Though much more common in the older populations, there has been a steady increase in cases among people younger than 50.

Weight: For men and women who are overweight or obese, the risk of developing and dying from colorectal cancer is greater.

Race: Of all racial groups in the United States, African Americans have the highest colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates.

Inherited mutations: About 5% of people develop colorectal cancer from inherited gene mutations. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer) are the most common inherited syndromes linked to colorectal cancer.

Family History: People with a first-degree family history of colorectal cancer are more likely to develop the disease. The risk is increased if more than one relative has been diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Individuals with a family history of adenomatous polyps or colorectal cancer should consider starting screening at the age of 45.

Personal history: Chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, can increase the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Over time, due to regular inflammation and irritation, people with IBD often develop dysplasia, a term that refers to abnormal development of cells in the lining of the colon and rectum.

Smoking: Though smoking is a well-known cause of lung cancer, it is linked to other cancers as well, including colorectal cancer. Long time smokers are more likely to develop and die from colorectal cancer.

Alcohol: Moderate to heavy alcohol use has been associated with the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Colorectal Cancer Prevention

The best way to prevent colorectal cancer is to start screening for it at the age recommended by a physician. In 2020, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force readjusted its recommendation for colorectal screening age 45 instead of 50 to combat increasing rates of early-onset colorectal cancer.

There are two main groups of tests for colorectal cancer screening:

Stool-based tests: Tests that check the stool for signs of cancer. These tests are less invasive but need to be done more often.

Visual exams: Tests that look at the structure of the colon and rectum for abnormal areas.

Symptoms of Colorectal Cancer

Signs and symptoms of colorectal cancer include:

Change in bowel habits: Changes in the consistency of the stool, diarrhea or constipation that persists for more than a few days.

Urgency: The feeling of needing to have a bowel movement but not feeling relief after having one.

Rectal bleeding: bright red blood from the rectum or blood in the stool.

Cramping: abdominal discomfort or pain from cramps or gas.

Weakness or fatigue.

Unexplained weight loss.

Signs and symptoms of colorectal cancer are not usually experienced in early stages. Symptoms vary depending on the size and location of the cancer.

Diagnosing Colorectal Cancer

For healthy individuals with no signs or symptoms of colorectal cancer, doctors recommend screening tests to look for signs of abnormalities in the colon and rectal wall or noncancerous polyps. The best chance for successful treatment of colorectal cancer is early diagnosis.

It is important to consult a doctor to determine at what age screening should be considered, taking into account family history, race, ethnicity and other risk factors. Together, with a doctor, patients can decide which screening tests are appropriate.

If signs or symptoms of colorectal cancer are evident, a doctor may recommend one or more of the following blood tests or procedures. Certain blood tests are used to help diagnose as well as monitor colorectal cancer.

Complete blood count: This test evaluates the types of cells in the blood, white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets, and can detect anemia, infections and leukemia. Some colorectal cancer patients can become anemic because of bleeding from a tumor or polyp in the colon or rectum.

Liver enzymes: A blood test may be used to test liver enzymes to measure liver function and protein production to determine if the cancer has spread to the liver.

Tumor markers: The most common tumor marker found in the blood for colorectal cancer is called carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). When tracked over time in patients already diagnosed with colorectal cancer, this tumor marker can help show how the patient is responding to treatment or be a warning the cancer has come back.

For patients already diagnosed with colorectal cancer, a doctor may order specific tests to help determine in what stage the cancer is in. Staging tests include diagnostic colonoscopy, proctoscopy and biopsy, as well as imaging screenings like CT, MRI and PET scans.

Stages of Colorectal Cancer

The most commonly used staging system for colorectal cancer is the TNM system, which was developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. The TNM system assesses the size and extent of the tumor (T-tumor), how far it has grown into the wall of the colon or rectum; whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N-node); and the presence and extent of metastasis (M-metastasis) to distant lymph nodes and organs like the liver or lungs.

Numbers or letters after the TNM assessment provide more details about each of the factors. The lower the stage the better the prognosis and treatment options.

Stage 0: The cancer is in its earliest stage and has not grown beyond the inner layer (mucosa) of the colon or rectum.

Stage 1: The cancer has grown through the thin muscle layer of the mucosa (muscularis mucosa) into the fibrous tissue beneath called the submucosa.

Stage 2: The cancer may have grown into the muscularis propria but has not spread to the nearby lymph nodes or distant sites.

Stage 3: The cancer has grown through the mucosa and submucosa into the outermost layer of the colon or rectum, the muscularis propria. It has spread to nearby lymph nodes but has not spread to distant sites.

Stage 4: The cancer might or might not have grown through the wall of the colon or rectum. It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes. It has spread to 1 or more distant organs or distant set of lymph nodes and might spread to distant parts of the peritoneum.

These stages can be further broken down based on the size of the original tumor and the extent to which the cancer has spread.

Treatments for Colorectal Cancer

Treatment for colorectal cancer is tailored to each patient and is dependent on the stage of the cancer, where it is located and other health concerns. Our multidisciplinary team includes multiple health care specialists including surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, gastroenterologists, pathologists, ostomy professionals, as well as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, psychologists, social workers and rehabilitation specialists. This team will work to personalize care for each patient.

The appendix and small intestine, also part of the gastrointestinal tract, can develop cancer tumors when the healthy cells become damaged or begin to grow rapidly. These two rare cancers are treated similarly to cancers of the colon and rectum.

Colorectal cancer treatment most commonly involves surgery to remove the cancer. Radiation therapy or chemotherapy might also be recommended among other treatments.

Endoscopic Procedures for Colorectal Cancer

Early-stage colorectal cancer can be treated with the following endoscopic techniques

Polypectomy: Most polyps and some very early-stage colorectal cancers can be removed completely during a colonoscopy. During the exam, a long flexible tube with a camera on the end (colonoscope) is inserted into the rectum and colon. Polyps are removed by passing a wire loop through the colonoscope to cut the polyp at the base off the wall of the colon with an electric current.

Endoscopic mucosal resection: Slightly more intricate than a polypectomy, larger polyps, and small cancers are removed during a colonoscopy using special tools to excise the polyp from the lining of the colon with a small amount of surrounding tissue.

Surgical Procedures Colorectal Cancer

Laparoscopic surgery: Larger polyps and cancers that cannot be removed during a colonoscopy can often be removed through laparoscopic surgery. This procedure is performed through small incisions in the abdominal wall by inserting instruments with attached cameras to display changes and abnormalities in the colon. Samples from lymph nodes in the area may also be taken during this operation.

Robotic surgery: Robotic surgery is similar to laparoscopic surgery in that it may be used to remove colorectal polyps or cancers with a minimally invasive surgical approach.

Open surgery: Open surgical procedures involve a large incision into the abdomen that may be needed in certain patients based on the specifics of their cancer or for patients who have had prior abdominal surgical operations.

Surgeries for Colorectal Cancer

For cancers that have grown into or through the colon or rectum wall, a surgeon may recommend surgical resection.

Partial colectomy: Also called a hemicolectomy or segmental resection, during this procedure the surgeon takes out the part of the colon with the cancer and a small amount of healthy tissue from either side. The two healthy sections of the colon are then reconnected. Nearby lymph nodes are also often removed during this procedure to be checked for cancer.

Total colectomy: In some cases, such as hundreds of polyps caused by familial adenomatous polyposis or inflammatory bowel disease, a surgeon may recommend removing all of the colon.

Colostomy: In cases where cancer blocks the colon or it is impossible to reattach the healthy portions of the colon, a colostomy may be recommended. A colostomy is a procedure where a piece of the colon is diverted to an artificial opening in the abdominal wall to bypass the damaged part of the colon. Stool is eliminated through this opening into a bag that fits securely to the skin. Surgeries for metastatic colorectal cancer: Sometimes surgery is done for colorectal cancer that has spread to other organs such as the liver, lungs, or peritoneum.

Low Anterior Resection (LAR): A procedure that is done for most rectal cancers and often involves the use of a temporary ostomy.

Abdominal Perineal Resection (APR): A procedure that is done for some rectal cancers and involves the use of a permanent ostomy.

Abdominal Perineal Resection (APR): This is a minimally invasive procedure in which a rectal polyp or early-stage rectal cancer may be removed through the anus, without an abdominal incision.

Surgeries for metastatic colorectal cancer: Sometimes surgery is done for colorectal cancer that has spread to other organs such as the liver, lungs, or peritoneum.

Many of these operations can be done through minimally invasive techniques, such as laparoscopy and robotic surgery. These techniques offer the potential benefits of a faster recovery, less incisional pain, and fewer wound infections and pulmonary complications.

Chemotherapy for Colorectal Cancer

Chemotherapy is a treatment that uses drugs that travel through the bloodstream to eliminate cancer cells.

Adjuvant chemo is given after surgery to kill any cancer cells that may have been left behind. Adjuvant chemotherapy helps lower the risk of cancer recurrence.

Neoadjuvant chemo, sometimes paired with radiology, is given before an operation to help reduce the cancer’s size to make it easier to remove with surgery.

In advanced cases, chemo may be used to help shrink tumors that have traveled to other organs like the liver.

Hepatic Artery Infusion Pump for Colorectal Cancer

Some patients with colorectal cancer that has spread to the liver may be candidates for hepatic artery infusion pump therapy, a treatment that uses a metal pump connected to a tube that is inserted into the hepatic artery to deliver chemotherapy directly to the tumor in the liver.

Radiation Therapy for Colorectal Cancer

Radiation is a treatment that uses high-energy rays or particles that destroy cancer cells. Sometimes used in combination with chemotherapy before surgery, radiation can help shrink cancers in the rectum or that have spread to other organs. Surgeons sometimes use radiation during surgery at the site where the cancer was to kill any cells left behind.

Immunotherapy for Colorectal Cancer

In some cases, the body’s best defense against colorectal cancer is the immune system. Immunotherapy is used to treat advanced colorectal cancer by training the immune system with drugs to recognize and destroy cancer cells. There are several FDA-approved immunotherapy options for colorectal cancer.

Targeted Drug Therapy for Colorectal Cancer

Specific drugs are sometimes used to target abnormalities in cancer cells. Similarly to chemotherapy, these targeted drugs travel through the bloodstream throughout the entire body to reach cancer cells that have spread to distant parts from the colon and rectum. Targeted drugs can also be used in combination with chemotherapy for more advanced cases where chemotherapy on its own is no longer working.

Watch-and-Wait (Non-operative Management) Approach for Rectal Cancer:

For some patient with rectal cancer who have undergone a combination of chemotherapy and or radiation therapy and their tumor has disappeared, our team may offer an approach called “Watch-and-Wait” or “Non-operative Management”. This approach allows as many as one-third of rectal cancer patients to avoid surgery in place of an intensive cancer surveillance program. If our cancer specialists see any sign of cancer regrowth during surveillance, evaluation and necessary treatment will occur quickly. We have a multi-disciplinary team of providers with years of experience supporting more than 40 patients, to date, with this approach.

Latest in Colorectal Cancer from the Cancer Center

Loading items....

Information reviewed by Jon Vogel, MD, in June 2024.