Contact UCHealth

Breast Cancer

Clinical Trials

Make a Gift

What Is Breast Cancer?

Breast cancer occurs when cells in the breast tissue develop changes (mutations) in their DNA, causing the cells to grow out of control. These abnormal cells form a tumor that can destroy normal body tissues and structures.

Breast cancer usually develops in either the lobules or the ducts of the breast. Lobules are the glands that produce milk, and ducts are the pathways that carry the milk from the glands to the nipples. Breast cancer can also occur in the fatty tissue or the fibrous connective tissue of the breast.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in women in the United States. About one in eight women will develop breast cancer at some point in their life.

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 310,720 new cases of invasive breast cancer and nearly 56,500 new cases of ductal carcinoma in situ are diagnosed in the U.S. each year, resulting in about 42,250 deaths. In Colorado, there are approximately 5,150 new cases of breast cancer each year.

Although breast cancer occurs primarily in women, men can also develop the disease.

Breast Cancer Prognosis and Survival Rates

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in women (after lung cancer) in the U.S. However, the number of women who died of breast cancer decreased by 40% from 1989 to 2007. Experts believe this was largely due to increased breast cancer screening, as well as advances in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer.

Since 2007, the number of women under age 50 who have died of breast cancer has plateaued, but the number of women age 50 and older who have died of the disease has continued to decrease.

The prognosis for a patient with breast cancer depends on the type of cancer and the stage at which it is diagnosed. The earlier breast cancer is detected and treated, the better the prognosis.

The five-year survival rate for patients with localized breast cancer (where the cancer has not spread outside of the breast to any lymph nodes or other sites in the body) is 99%. The majority of cases (about 66%) are diagnosed at this stage, although younger women are less likely to be diagnosed at this stage than older women, likely because most breast cancer screening does not begin until age 40. The survival rate for node-positive breast cancer (where the cancer has spread outside the breast to nearby structures or lymph nodes) is 86%.

The survival rate drops as the cancer spreads beyond the immediate area of the breast. The five-year survival rate for patients with metastatic breast cancer, where the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body such as the lungs, liver, or bones, is 28%. This accounts for about 6% of all initial breast cancer diagnoses.

Why Come to CU Anschutz Cancer Center for Breast Cancer

As the only National Cancer Institute Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in the state of Colorado and one of only four in the Rocky Mountain region, the University of Colorado Anschutz Cancer Center has doctors who provide state-of-the-art, multidisciplinary, patient-centered breast cancer care and researchers focused on diagnostic and treatment innovations.

The CU Anschutz Cancer Center is home to the Diane O'Connor Thompson Breast Center on the Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, Colorado; the UCHealth Breast Center – Cherry Creek in Denver; the UCHealth Breast Center - Highlands Ranch Hospital in Highlands Ranch; and the UCHealth Lone Tree Breast Center. These multidisciplinary clinics offer patients an “all in one” approach to clinical care, overseen by world-class medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, plastic and reconstructive surgeons, radiation oncologists, radiologists, genetic counselors, physical therapists, lymphedema therapists, breast imaging patient navigators, breast cancer nurse navigators, and others who collaborate on both primary treatment and aftercare.

Contact the Breast Multidisciplinary Clinic at 720-848-1030.

→ Oncology Nurse Turned Cancer Survivor Is Dedicated to Improving the Quality of Care for Patients

There are numerous breast cancer clinical trials being conducted by CU Anschutz Cancer Center members all the time. These trials offer patients additional treatment options investigating new treatments designed to improve patient outcomes.

The Women’s Cancer Developmental Therapeutics Program (WCDTP) at the CU Anschutz Cancer Center seeks to increase the development of novel cancer therapies in ovarian cancer and other gynecologic cancers with the goal of decreasing cancer-related morbidity and mortality for patients. Additionally, the WCTD seeks to increase access to phase I and II clinical trials of novel cancer therapies for patients with gynecologic and breast cancers.

CU doctors are also experienced in treating a variety of benign (non-cancerous) breast conditions. Although benign breast conditions are not life-threatening, some are linked with a higher risk of developing breast cancer later in life. The CU breast cancer risk assessment and prevention program offers the tools and experience to determine patient risk.

Some non-cancerous breast conditions include breast pain, nipple discharge, fibrosis and simple cysts, ductal or lobular hyperplasia, atypical proliferative changes, adenosis, fibroadenomas, intraductal papillomas, granular cell tumors, fat necrosis, oil cysts, mastitis, and duct ectasia, phyllodes tumors, and high-risk proliferative lesions.

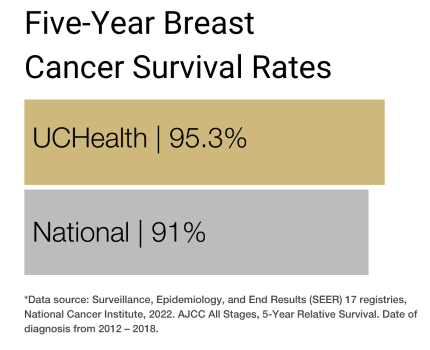

Our clinical partnership with UCHealth has produced survival rates higher than the state average for all stages of breast cancer.

Types of Breast Cancer

Different types of breast cells can become cancerous, and the type of cell affected determines the type of breast cancer. Breast cancers are categorized by looking at the cells under a microscope. Doctors use this information to understand the expected growth pattern and speed, as well as which treatments may work best.

Most breast cancers are carcinomas: tumors that start in the epithelial cells that line organs and tissues throughout the body. When tumors form in the breast, they are usually a specific type of carcinoma called adenocarcinoma, which starts in the cells of the lobules (the milk-producing glands of the breast) or the milk ducts (the pathways that carry milk from the lobules to the nipples).

Breast cancers can also be categorized based on whether the tumor has spread or not. They are divided into two main categories: non-invasive (also called in situ) and invasive (also called infiltrating).

Common Non-Invasive Breast Cancers

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) tumors are confined to the milk ducts and have not invaded the surrounding breast tissue.

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) tumors grow in the lobules and have not invaded the surrounding breast tissue.

Common Invasive Breast Cancers

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) is the most common type of breast cancer. These tumors have developed in the milk ducts and invaded nearby breast tissue.

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) tumors have developed in the lobules and have invaded nearby breast tissue.

Once the tumor has spread outside the lobules or milk ducts, it can begin to spread to other nearby tissues, lymph nodes, and organs.

Rare Breast Cancers

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare and aggressive type of invasive breast cancer that accounts for only 1% to 5% of all breast cancer diagnoses. IBC causes cells to block the lymph channels and nodes near the breast, preventing them from draining properly. Instead of forming a tumor, IBC causes the breast to swell. The breast may appear red and feel warm, pitted and thick, like an orange peel. This type of breast cancer tends to grow and spread quickly.

Paget’s disease is a rare condition, accounting for only about 1% to 3% of breast cancer diagnoses. It begins in the ducts of the nipple and spreads to the skin and areola of the nipple. Although it is usually non-invasive, it can become invasive.

Phyllodes tumor is an extremely rare type of breast cancer that forms in the connective tissue (or stroma) of the breast. Although most phyllodes tumors are benign, some can become cancerous (or malignant).

Angiosarcoma is a rare type of tumor that grows in the blood vessels or lymph vessels of the breast and accounts for less than 1% of all breast cancer diagnoses.

Risk Factors for Breast Cancer

Breast cancer occurs when some breast cells begin to multiply rapidly, accumulating to form a lump or mass called a tumor. Researchers have identified several hormonal, lifestyle, and environmental factors that may increase a person’s risk of developing breast cancer. These are called risk factors.

Gender: Women are 70 to 100 times more likely than men to develop breast cancer.

Age: The risk of breast cancer increases with age. Most invasive breast cancers are diagnosed in women over age 55.

Race and ethnicity: People with Ashkenazi or Eastern European Jewish ancestry may be more likely to get breast cancer. White women are more likely to develop breast cancer than Black women. However, among women younger than 45, the disease is more common in Black women than in white women. Black women are also more likely to die from the disease. Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native women are the least likely to get breast cancer.

Height: Studies have found that taller women have a higher risk of breast cancer than shorter women.

Dense breast tissue: Women with dense breast tissue (made up of more glandular and fibrous tissue and less fatty tissue) have a higher risk of breast cancer than women with average breast density.

Personal history of breast conditions: Patients who have been diagnosed with certain conditions such as atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia, lobular carcinoma in situ, and papillomatosis have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Personal history of breast cancer: Patients who have already had breast cancer in one breast have an increased risk of developing cancer in the other breast.

Family history and genetics: People with a mother, sister, or daughter who has been diagnosed with breast cancer have a higher risk of developing breast cancer. Those with a family history of ovarian cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, or pancreatic cancer may also have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Several inherited gene mutations can increase the risk of breast cancer, particularly the tumor suppressor gene mutations BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2. Other gene mutations or hereditary conditions that may increase a person’s risk of breast cancer include Lynch syndrome, Cowden syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, ataxia telangiectasia, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, and the CHEK2 gene.

Radiation exposure: People who received radiation treatments to the chest as a child or young adult have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Weight: People who are overweight or obese have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Early menstruation: Women who started menstruating before age 12 have a higher risk of breast cancer.

Late menopause: Women who begin menopause after age 55 are more likely to develop breast cancer.

Having a first child at an older age: Women who give birth to their first child after age 35 may have a greater risk of breast cancer.

Having never been pregnant: Women who have never been pregnant have a higher risk of developing breast cancer than do women who have had one or more pregnancies.

Not breastfeeding: Research suggest that breastfeeding may slightly lower breast cancer risk, especially when it is continued for a year or more.

Postmenopausal hormone therapy: Women who take hormone therapy medications to treat the symptoms of menopause have a higher risk of breast cancer.

Hormonal birth control: Some studies suggest that the use of oral contraceptives and other hormonal birth control methods such as the Depo-Provera shot and hormone-releasing IUDs, implants, patches, and rings may slightly increase the risk of breast cancer.

Alcohol consumption: Drinking alcohol increases the risk of breast cancer.

Breast implants: Although breast implants have not been linked to an increased risk of the most common types of breast cancer, recipients may be more like to develop a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma called breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma, which can form in scar tissue around the implant.

Exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES): From the 1940s to the early 1970s, some pregnant women were given an estrogen-like drug called DES that was thought to lower their chances of miscarriage. Women who took DES and women whose mothers took DES have a slightly higher risk of developing breast cancer.

Preventing Breast Cancer

In addition to avoiding the risk factors above (when possible) and maintaining a healthy lifestyle through diet and exercise, some women with a heightened risk of breast cancer may explore preventive measures such as:

Genetic counseling and testing: Women with a family history of breast cancer may benefit from genetic counseling. A genetic counselor will review the patient’s family history to see how likely it is that they have a family cancer syndrome such as Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (HBOC) syndrome, which is linked to mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. If so, they may recommend blood panel tests to look for these and other gene mutations that can increase a person’s risk for breast cancer. These findings can help guide further preventive measures and screenings.

Preventive medications: Some hormone-blocking drugs can help prevent breast cancer. This approach is called chemoprevention or endocrine prevention. These drugs include medicines like tamoxifen and raloxifene that block the action of estrogen in breast tissue or aromatase inhibitors that block overall estrogen production.

Preventive surgery: Women with a very high risk of breast cancer, such as those with a BRCA gene mutation, may choose to have their breasts surgically removed as a preventive measure. This is called a prophylactic mastectomy and reduces the risk of developing breast cancer by 90% to 95%. Prophylactic mastectomies can be performed with immediate breast reconstruction with the breast surgeon working with the plastic surgeon. When possible, nipple-sparing mastectomies are offered to enhance the long-term cosmetic outcomes of the procedure. Preventive mastectomies eliminate the need to have screening mammograms and MRIs. However, since there is a small amount of remaining breast tissue, high-risk women are taught how to monitor the skin for any changes.

Women with a high risk of breast and ovarian cancer may also consider the preventive removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes, since the ovaries are the body’s main source of estrogen. This is called a prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and reduces the risk of both breast cancer and ovarian cancer. Some women choose to initially remove only the fallopian tubes (salpingectomy) and retain the ovaries in order to preserve fertility. Salpingectomy may reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. Once childbearing is complete (or if a woman is unable to or chooses not to have children), the ovaries can be removed. Preventive removal of the ovaries is not recommended prior to age 35 or before a woman has completed her childbearing. Timing of preventive surgery is a personal decision.

Symptoms of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer can usually be treated successfully if it is diagnosed before the cancer has spread. The most common symptom of breast cancer is a new lump or mass in the breast. A painless, hard mass with irregular edges is more likely to be a breast cancer tumor, but they can also be painful, soft, and/or round.

Other potential breast cancer signs include:

- Swelling of all or part of a breast.

- Change in the size, shape, temperature, or appearance of a breast.

- Skin dimpling or pitting.

- Breast or nipple pain.

- Nipple retraction or inversion.

- Red, dry, flaking, peeling, scaling, crusting, or thickened nipple or breast skin.

- Nipple discharge.

- Swollen lymph nodes (especially under the arm or around the collar bone).

These symptoms can also be caused by conditions other than breast cancer. It is important to get any new breast mass, lump, or breast change checked by an experienced medical professional.

Screening for Breast Cancer

Screening is used to look for cancer before a person shows any symptoms of the disease. The most common screening method for breast cancer is a mammography.

Mammograms are low-dose x-rays of the breast. Mammograms are performed using a special machine with two plates that compress the breast to spread the tissue apart and produce a better picture. Research shows that women who have regular mammograms are more likely to be diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. As a result, they are less likely to need aggressive treatment (like surgery to remove the entire breast and chemotherapy) and are more likely to be cured. Traditional mammograms create a two-dimensional image of the breast. A newer type of mammogram called digital breast tomosynthesis creates a three-dimensional image of the breast and has become more common in recent years. All of the CU Anschutz Cancer Center breast imaging centers utilize tomosynthesis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans may also be used to screen for breast cancer in women with higher-than-average risk. MRIs use radio waves and strong magnets to create detailed pictures of the inside of the breast. Breast MRIs are performed using a special machine called an MRI with dedicated breast coils.

Many different medical organizations offer breast cancer screening guidelines for women with average risk of breast cancer and those with high risk for breast cancer. The recommendations below are general guidelines, but it’s important for women to consult with their doctors to determine the best individual screening schedule.

Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations for Women with Average Risk

Women with average risk of breast cancer:

- Do not have a personal history of breast cancer.

- Do not have a strong family history of breast cancer.

- Do not have a genetic mutation known to increase risk of breast cancer.

- Have not had chest radiation therapy before age 30.

According to the American Cancer Society, women with average risk between 40 and 44 should have the option to get a mammogram every year.

Women with average risk between 45 to 54 should get a mammogram every year.

Women with average risk 55 and older can decrease mammogram frequency to every other year or continue yearly mammograms.

Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations for Women with High Risk

Women with high risk of breast cancer:

- Have a known BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation.

- Have a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation.

- Had radiation therapy to the chest between the ages of 10 and 30.

- Have Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Cowden syndrome, or Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome (or have first-degree relatives with one of these syndromes).

- Have a personal history of breast cancer, ductal carcinoma in situ, lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical ductal hyperplasia, or atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH).

- Have extremely or heterogeneously dense breasts.

According to the American Cancer Society, women with high risk should get a breast MRI and a mammogram every year, starting at age 30. And for women who have a known BRCA mutation, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends yearly MRI screening beginning at age 25.

Diagnosing Breast Cancer

If a doctor detects an abnormality during a physical breast exam or during screenings like a mammogram or MRI, they may recommend further tests to determine whether the patient has breast cancer. Based on their findings, the doctor may also refer the patient to a specialist, such as a breast surgeon or surgical oncologist.

The only definitive way to diagnose breast cancer is with a biopsy, but the process may involve many steps, including all or some of the following:

Imaging Tests for Breast Cancer

Imaging tests can show where the tumors are located and whether they have spread from the original site to other parts of the breast and beyond. The images are reviewed by a radiologist, a doctor who specializes in interpreting imaging tests.

In addition to mammograms and MRIs, a doctor may perform an imaging test called an ultrasound to detect breast cancer. Ultrasounds use sound waves to create an image of the inside of the breast. They

are especially useful for looking at lumps or other changes in women with dense breast tissue, and can help doctors distinguish between benign, fluid-filled cysts and solid masses that are more likely to be cancerous. Ultrasound is also frequently

used to evaluate the lymph nodes under the arm if a breast lump is suspicious.

Biopsies for Breast Cancer

During a biopsy, a doctor extracts a sample (or multiple samples) of tissue from the suspected tumor site. These are sent to a laboratory for analysis by a pathologist to determine whether the cells in the sample are cancerous. They may also look for certain hormone receptors that can affect prognosis and treatment. There are different kinds of breast biopsies, and the type of biopsy a patient receives is determined by several factors, including the size and location of the tumor, the number of tumors, and the type of breast cancer suspected.

During a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, a doctor uses a thin, hollow needle attached to a syringe to remove (aspirate) fluid and small pieces of tissue from the tumor. If the tumor is near the surface of the skin, the doctor may aim the needle by feel. If the tumor is deeper inside the breast, the doctor (typically an interventional radiologist) may use a mammogram, MRI, or ultrasound to guide the needle.

A core needle biopsy is usually the preferred type of biopsy for diagnosing breast cancer. During this type of biopsy, a doctor uses a hollow needle to remove a small cylinder of tissue from the tumor. Core needle biopsies are usually done with local anesthesia, where a numbing agent is injected into the skin and other tissues over the biopsy site, although some procedures may require general anesthesia (where the patient is asleep). As with a fine needle aspiration, the doctor may guide the needle by feel or with an imaging scan.

In rare circumstances, a surgeon may perform a surgical or open biopsy to diagnose breast cancer. In these cases, the surgeon will usually remove the entire mass or tumor as well as some of the surrounding breast tissue to ensure no cancer cells are left behind (called a margin). These biopsies are usually performed in an operating room while the patient is under general anesthesia, though they may also be performed using a nerve block. Open surgical biopsies are typically only advised if the core needle biopsy is inconclusive or a patient is unable to have a core needle biopsy.

Because breast cancer can spread to the lymph nodes under the arms (called the axillary lymph nodes), the radiologist may also examine the armpit lymph nodes with ultrasound. If any abnormal lymph nodes are seen with ultrasound, a fine needle aspiration

or core biopsy of the lymph node may be performed. The biopsy is done with ultrasound to safely guide the needle into the node and obtain a small core of tissue. This information helps to plan cancer treatment.

Stages of Breast Cancer

After diagnosing breast cancer, the doctor will identify the stage of the disease. The stage is determined by several factors, including the size of the tumor and whether and how far it has spread beyond the breast. The stage impacts both the prognosis and treatment options.

Many of the same tests used to screen for and diagnose breast cancer are also used to identify the stage, such as mammograms, MRIs, ultrasounds, blood tests, and biopsies. Staging may also require additional procedures, such as bone scans, computerized tomography (CT) scans, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. This is called clinical staging. The stage may also be determined after surgery based on what is found during the operation to remove breast tissue and lymph nodes. This is called pathological or surgical staging.

The system most doctors use to stage breast cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM system. The TNM system assesses the size and extent of the tumor (T-tumor); whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N-node); and the presence and extent of spread or metastasis (M-metastasis) to distant lymph nodes, bones, and organs.

Breast Cancer Biology

For breast cancer, the TNM system also incorporates the presence or absence of certain hormone receptors and tumor biomarkers and the grade of the cancer (how normal or abnormal the cells appear under a microscope).

Estrogen and progesterone receptors are found in breast cancer cells that depend on those hormones to grow. If the cells have estrogen receptors, the cancer is called ER-positive breast cancer. If the cells have progesterone receptors, the cancer is called PR-positive breast cancer. If the cells do not have either of these receptors, the cancer is called ER/PR-negative breast cancer. About two-thirds of all breast cancers are ER and/or PR positive.

Learning whether a tumor has estrogen and/or progesterone receptors helps determine the risk of recurrence (when cancer comes back after treatment) and whether the cancer can be treated with hormone therapy. For this reason, all patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer or breast cancer that has metastasized or recurred should have their cancer cells tested for estrogen and progesterone receptors. The most common method to test for these receptors is called immunohistochemistry (IHC). The tissue sample for IHC may be obtained during a biopsy or surgery.

Some breast cancer patients have tumors with higher levels of a protein called HER2. HER2 is a growth-promoting protein found on the outside of all breast cells, but breast cancer cells with higher-than-normal levels of HER2 are called HER2-positive. These cancers tend to grow and spread faster than other breast cancers, but they are also more likely to respond to certain drug therapies that target the HER2 protein.

Since it can affect treatment, women who have been diagnosed with invasive breast cancer should have their tumor tested for HER2. As with testing for hormone receptors, the tissue sample for HER2 testing usually comes from a core biopsy or surgery. The sample is then tested for HER2 levels with either immunohistochemistry or fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH).

Triple-negative breast cancer is an faster growing type of invasive tumor that accounts for about 15% of all breast cancer diagnoses. To be diagnosed as triple-negative breast cancer, a tumor must lack estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and HER2 protein over-expression. This type of breast cancer tends to grow and spread more quickly than other types of breast cancer but responds to chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and antibody-drug conjugates.

Breast Cancer Stages

After the TNM assessment, the doctor will assign an overall stage, starting at 0 (this is considered non-invasive or in situ) and then ranging from 1 to 4 (these are considered invasive). These stages can be further broken down depending on the size of the tumor and the extent of the cancer’s spread. In general, the lower the stage the better the prognosis and treatment options.

Stage 0: The cancer cells are confined to the lobules or ducts in the breast and have not spread into nearby tissue. This is also called non-invasive or in situ cancer.

Stage 1A: The primary tumor is 2 cm wide or less and the cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 1B: Either there is no primary tumor, or the primary tumor is smaller than 2 cm wide. The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 2A: The primary tumor is smaller than 2 cm wide and the cancer has spread to one and three nearby lymph nodes, or the primary tumor is between 2 and 5 cm wide and the cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 2B: The primary tumor is between 2 and 5 cm wide and the cancer has spread to one to three axillary (armpit) lymph nodes, or the primary tumor is larger than 5 cm wide and the cancer has not spread to any lymph nodes.

Stage 3A: The primary tumor can be any size and the cancer has spread to four to nine axillary lymph nodes or has enlarged the internal mammary lymph nodes. Or the primary tumor is larger than 5 cm wide and the cancer has spread to one to three axillary lymph nodes or any number of breastbone lymph nodes.

Stage 3B: The tumor has invaded the chest wall or skin and the cancer may or may not have invaded up to nine lymph nodes.

Stage 3C: The cancer has spread to 10 or more axillary lymph nodes, lymph nodes near the collarbone, or internal mammary nodes.

Stage 4: The tumor can be any size and the cancer has spread to nearby and distant lymph nodes as well as distant organs such as the bones, lungs, or liver. This is also referred to as metastatic breast cancer

Treatments for Breast Cancer

The treatment for breast cancer is customized to each patient and depends on the size of the tumors, the stage at which the patient is diagnosed, whether the cancer cells are sensitive to hormones, results of HER2 testing, and the patient’s general

health. Breast cancer care teams may include multiple health care specialists, including breast surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, plastic surgeons, radiologists, genetic

counselors, physical therapists, lymphedema therapists, breast imaging patient navigators, and breast cancer nurse navigators, as well as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and rehabilitation specialists.

CU Cancer Center doctors offer specialized care for patients with breast cancer.

→ Breast Cancer Patient’s Advice: Take It One Treatment at a Time

The primary treatments for breast cancer include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Most patients receive one or more of these treatments during the course of their breast cancer treatment. Some patients

may also be eligible to participate in clinical trials — doctor-led research studies of new or experimental procedures or treatments.

Surgery for Breast Cancer

Surgery is a primary treatment for breast cancer that has not spread beyond the breast or lymph nodes. The most common surgeries to treat breast cancer are lumpectomies and mastectomies. For women with invasive breast cancer, surgical evaluation of the lymph nodes is performed with a procedure called sentinel node biopsy.

During a lumpectomy, the surgeon removes the tumor and a small margin of surrounding healthy tissue. This type of surgery is usually best for removing smaller tumors in patients with early-stage cancer. Some patients with larger tumors may undergo chemotherapy or hormonal therapy before surgery to shrink the tumor to make it possible to remove the cancer completely with a lumpectomy procedure.

During a mastectomy, the surgeon removes the entire breast, including all of the breast tissue. Some women may also receive a double mastectomy, in which both breasts are removed. Skin-sparing mastectomies and nipple-sparing mastectomies are becoming common operations for breast cancer to improve the appearance of the breast. Some women with a high risk of developing breast cancer choose to have preventive mastectomies.

When breast cancer spreads outside of the breast, it often travels to the lymph nodes under the arm. A sentinel lymph node biopsy is performed at the time of the lumpectomy or mastectomy to determine if the cancer has spread to the nodes. There are many lymph nodes under the arm. The sentinel node(s) are the first nodes to which the cancer would spread, if it were to spread. The surgeon injects a blue dye and a small dose of radiation called Tc-99 into the breast after anesthesia. Within one to two minutes, the blue dye and Tc-99 travel through the lymph channels to the sentinel nodes in the armpit. The surgeon can identify these nodes by carefully looking for the nodes that are blue and by using a hand-held detector to find the nodes with the radiation. These nodes are then removed and sent for biopsy.

If the sentinel nodes are negative for spread of cancer, this means that the remaining nodes in the armpit are also cancer free. If cancer is found in only one or two sentinel nodes, the remaining lymph nodes in the armpit require further treatment. In most cases, the remaining lymph nodes are treated with radiation. If three or more sentinel nodes show cancer, a more extensive surgery called axillary node dissection is recommended. During this surgery, 10 to 15 lymph nodes are removed to determine if the cancer has spread beyond the sentinel nodes.

Axillary lymph node dissection is a surgery to remove 10 to 15 lymph nodes in the armpit. This surgery is recommended when the lymph nodes are obviously enlarged and a biopsy is positive for cancer spread. Strategies to reduce the need for requiring an axillary lymph node dissection are to recommend chemotherapy before having surgery. For some patients, chemotherapy before surgery will clear the cancer from the lymph nodes and allow a more limited axillary surgery.

Reconstructive surgery may be performed after a lumpectomy or mastectomy to rebuild the shape of the breast. It may be done at the same time as the mastectomy or later. CU Cancer Center plastic surgeons offer various types of breast reconstruction,

including tissue expansion with implants, direct-to-implant reconstruction, tissue-transfer reconstructions (procedures that use muscle and tissue from elsewhere in the body), and oncoplastic reconstruction.

Radiation Therapy for Breast Cancer

Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in radiation therapy is a radiation oncologist. Adjuvant radiation therapy is given after surgery, usually to patients who have undergone a lumpectomy.

External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the most common radiation treatment and uses a machine located outside the body to focus a beam of x-rays on the area with the cancer. Patients who had a lumpectomy will likely receive radiation

to the entire breast (called whole breast radiation), as well as an extra boost of radiation to where the tumor was removed. Patients who had a mastectomy will usually receive radiation to the chest wall, the mastectomy scar, and any places where

drains exited the body after surgery. If the cancer spread to the axillary lymph nodes, this area may receive radiation, as well.

Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer

Chemotherapy drugs target rapidly dividing cells (including cancer cells) and are very effective for certain types of breast cancer. Like radiation therapy, chemotherapy may be given before surgery to shrink tumors or after surgery to reduce the risk of the cancer returning.

Chemotherapy for breast cancer can be administered intravenously (injected into your vein or a port placed for administration) or by mouth. This type of chemo is called systemic chemotherapy because the drugs enter the bloodstream and attack cancer cells everywhere in the body.

Chemotherapy is often most effective when a combination of drugs is used for early stage cancer. For patients with metastatic cancer, single agent chemotherapy is often used. Common chemotherapy drugs for breast cancer include doxorubicin, taxanes (such as paclitaxel, docetaxel, and protein-bound paclitaxel), REMOVE: 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or capecitabine, cyclophosphamide, carboplatin, cisplatin, eribulin, gemcitabine, REMOVE: ixabepilone, REMOVE:methotrexate, and vinorelbine. Newer drugs called antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) can deliver chemotherapy more directly to cancer cells. ADCs include sacituzumab govitecan and trastuzumab deruxtecan. There are many different chemotherapy regimens for breast cancer depending on the stage of the cancer, the biologic subtype, and whether the treatments are curative or palliative.

Targeted Drug Therapy for Breast Cancer

Targeted therapy focuses on the specific genes, proteins, or tissue environments that contribute to breast cancer, limiting damage to non-cancerous cells and tissues.

Drug Therapy for Hormone Receptor-positive Breast Cancer

Hormone therapy (also called endocrine therapy) for breast cancer involves the use of drugs to block the binding or production of certain hormones. It is often an effective treatment for tumors that test positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors (called ER positive or PR positive tumors), as these types of tumors use hormones to fuel their growth. Hormone therapy can be used in the adjuvant setting after curative breast cancer treatment to prevent recurrence or in the metastatic setting to control cancer and prevent progression.

Tamoxifen is a hormonal medication that blocks the binding of estrogen to cancer cells. Although tamoxifen acts like an anti-estrogen in breast cells, it acts like estrogen in other tissues. Because of this, it is called a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). Tamoxifen can be used in women who are pre- or post-menopausal.

Fulvestrant (Faslodex) is a hormonal drug that blocks and damages estrogen receptors. Unlike a SERM, fulvestrant acts like an anti-estrogen throughout the body. Because of this, it is called a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD).

Aromatase inhibitors are another group of hormonal medicines that prevent the production of estrogen in the body. Aromatase inhibitors can only be used in women who are post-menopausal or take medications to shut off their ovarian function.

Elacestrant is an oral SERD that can work in breast cancers that have developed mutations in the ESR1 (the gene that encodes for the estrogen receptor).

Ovarian suppression is the use of medicines to stop the ovaries from producing estrogen. Ovarian ablation (also called oophorectomy) is the surgical removal of the ovaries.

For women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancers, certain targeted therapy drugs can make hormone therapy more effective. These include CDK4/6 inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, and PI3K/AKT inhibitors. The landscape of available hormonal and targeted therapies is rapidly changing with many new drug approvals expected every year. Check with your doctor to discuss the treatments that may be available to you.

Drug Therapy for HER2-positive Breast Cancer

Certain drugs can block signaling through epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), a protein that helps breast cancer cells grow and spread. By targeting cells that make too much HER2, the drugs destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy cells.

Drug Therapy for Women with BRCA os PALB2 Gene Mutations

PARP proteins normally help repair damaged DNA inside cells, and drugs called PARP inhibitors work by blocking these proteins. Because cancer cells with a mutated BRCA or PALB2 gene already have difficulty repairing damaged DNA, blocking the PARP proteins can destroy these cells.

Immunotherapy for Breast Cancer

Immunotherapy (also called biologic therapy) uses medicines to stimulate the body’s own immune system to combat cancer. It is most commonly used patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Immunotherapy is often combined with chemotherapy to treat early or advanced breast cancer.

The main type of immunotherapy drugs used for breast cancer are immune checkpoint inhibitors, which target checkpoint proteins on immune cells that need to be turned on or off to trigger an immune response. Breast cancer cells sometimes use these checkpoint proteins to avoid being attacked by the immune system, so checkpoint inhibitor drugs can help to restore the appropriate immune response against cancer cells.

Scarlet Doyle's Breast Cancer Journey

Latest in Breast Cancer from the Cancer Center

Loading items....

Information reviewed by Jennifer Diamond, MD, in August 2025.