Contact UCHealth

Blood Cancer

Contact Children's Hospital CO

Clinical Trials

Make a Gift

What Is Blood Cancer?

Unlike many forms of cancer that cause tumors to form, blood cancers, also called hematologic cancers, affect the cells that make up the blood, bone marrow, and lymph nodes. Blood is a vitally important fluid that performs a number of functions in the body, including transporting oxygen from the lungs to the cells of the body, providing cells with nutrients, transporting hormones, removing waste products, regulating body temperature and pH balance, and fighting infection.

Blood cancers occur when abnormal blood cells begin growing out of control, interrupting the function of normal blood cells. Many blood cancers develop in the bone marrow where blood is produced.

There are three main types of blood cancers: leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. Each of these has various subtypes as well. Blood cancers account for about 9.4% of all new cancer diagnoses.

According to the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, an estimated 184,720 new cases of blood cancer will be diagnosed in the U.S. in 2023. Leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma are expected to cause the deaths of an estimated 57,380 people in the US in 2023. In Colorado, there are approximately 2,660 new cases of blood cancer each year.

The prognosis for a patient with blood cancer depends on the blood cancer type and subtype.

Why Come to CU Anschutz Cancer Center for Blood Cancer

As the only National Cancer Institute Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in Colorado and one of only four in the Rocky Mountain region, CU Anschutz Cancer Center has doctors who provide top-notch, patient-centered blood cancer care, and researchers focused on diagnostic and treatment innovations. In addition, as a National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) institution, faculty members from the CU Anschutz Cancer Center are members and often leaders of the guidelines committees that develop the treatment algorithms for every blood cancer used by most blood cancer doctors worldwide. They are true experts in their field and this translates into the care they provide and the cutting-edge clinical trials they offer.

There are a number of blood cancer clinical trials being offered by CU Anschutz Cancer Center members at any given time, including leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. These trials offer patients additional options to traditional blood cancer treatment and can result in remission or increased life spans.

→ Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Won’t Slow World Champion Triathlete Down

As a leader in blood cancer research, the University of Colorado School of Medicine’s Division of Hematology hosts an annual Blood Cancer Boot Camp, a continuing education

event focused on providing the most recent updates on blood cancer care to health care workers across the country. You can find additional educational activities including Denver ASH Review, Robert H. Allen, MD, Memorial Hematology Symposium, and more on the Hematology Continuing Education home page.

For more information on pediatric blood cancer, and to learn more about the care team and conditions treated visit the Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders at Children’s Hospital Colorado.

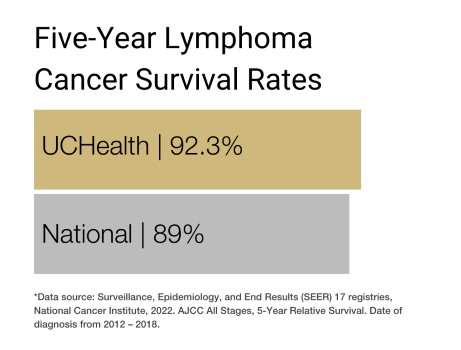

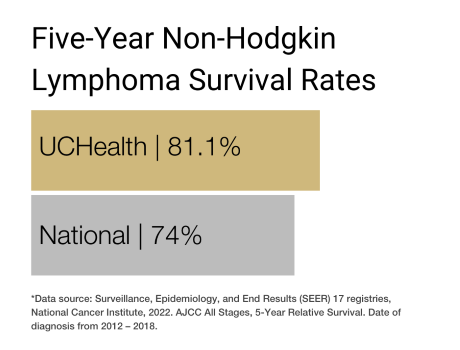

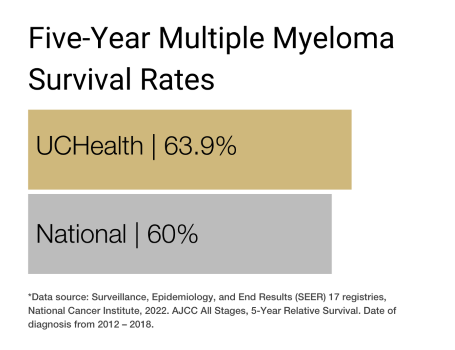

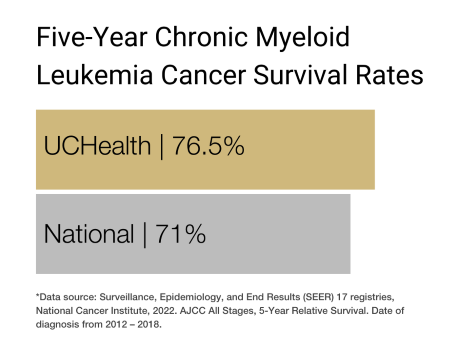

Our clinical partnership with UCHealth has produced survival rates higher than the state average for lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic myeloid leukemia, and multiple myeloma.

Blood Cancer Types

Different types of blood cells can become cancerous, and the type of cell affected determines the type of blood cancer. They are categorized by looking at the cells under a microscope and other very sophisticated diagnostic tests. Doctors use this information to understand the expected growth pattern and speed, as well as which treatments may work best.

The three primary types of blood cancer are leukemia, lymphoma (Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin), and multiple myeloma.

Leukemia originates in the blood and bone marrow. It usually occurs when the body creates too many abnormal white blood cells and interferes with the bone marrow’s ability to make red blood cells and platelets, though some leukemias start in other kinds of blood cells.

Leukemia accounts for about one-third of all blood cancer diagnoses and was the sixth most common cause of cancer deaths in both men and women in the U.S. from 2012 to 2016. It is the most common cancer in children and teens, accounting for almost one-third of all childhood cancer diagnoses.

Lymphoma develops in the lymphatic system in cells called lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell that helps the body fight infections. Lymphoma accounts for nearly half of all blood cancer diagnoses.

Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by the presence of an abnormal lymphocyte called the Reed-Sternberg cell. Hodgkin lymphoma is considered one of the most curable types of cancer. The Reed-Sternberg cell lymphocyte is not present in Non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Multiple myeloma begins in the blood’s plasma cells — a type of white blood cell the forms in the bone marrow. Multiple myeloma accounts for about 18% of all blood cancer diagnoses.

Risk Factors for Blood Cancer

While the exact cause of most blood cancers is unknown, certain risk factors — behaviors or conditions that increase a person’s likelihood of developing the cancer — have been linked to the disease.

Gender: Men are slightly more likely than women to develop blood cancer.

Age: The risk of most blood cancers increases with age but there are some exceptions. For instance, most cases of acute lymphocytic leukemia occur in people under 20 years old, and Hodgkin lymphoma is most common in adults in their 20’s and 30’s.

Race: The incidence of multiple myeloma is twice as high in Black people as in Caucasians. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is more common in Caucasians.

Geography: Hodgkin lymphoma is most common in North America and northern Europe.

Family history: Close relatives of patients with blood cancer may be at an increased risk for developing the disease, but this is uncommon, and these diseases are typically not inherited.

Genetic syndromes: Some genetic syndromes seem to raise the risk of certain blood cancers. These include Down syndrome, Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia, Blackfan-Diamond syndrome, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.

Blood disorders: Certain blood disorders — including chronic myeloproliferative disorders such as polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis, and essential thrombocytopenia — increase the chances of developing leukemia.

Compromised immune system: People with a compromised immune system may have a higher risk of developing lymphoma. This includes patients with conditions such as HIV/AIDS, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and celiac disease, as well as those taking immunosuppressant drugs to prevent organ transplant rejection.

Viruses and infections: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), known for causing mononucleosis in young adults, may be linked to some lymphomas. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus, human herpes virus 8, and hepatitis C virus may also increase risk.

Personal history of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS): A small percentage of patients with MGUS may be at increased risk for multiple myeloma.

Previous cancer therapy: Certain types of chemotherapy and radiation therapy are considered risk factors for some types of leukemia.

Radiation: Exposure to high-energy radiation or intense exposure to low-energy radiation can increase the risk of some types of leukemia.

Chemicals: Long-term exposure to certain pesticides, fertilizers, herbicides, insecticides, and industrial chemicals (such as benzene) may increase a person’s chances of developing blood cancer.

Smoking: Smoking has been linked to an increased risk of developing leukemia.

Obesity: Research shows that obesity may lead to an increased risk of lymphoma and multiple myeloma.

Symptoms of Blood Cancer

Blood cancer symptoms often vary depending on the type of cancer diagnosed. Many resemble flu-like symptoms but do not go away after a few weeks. Some signs of blood cancer include:

- Fever.

- Chills.

- Persistent fatigue and weakness.

- Mental fogginess or confusion.

- Dizziness.

- Nausea and/or vomiting.

- Loss of appetite.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Constipation.

- Increased thirst and urination.

- Night sweats.

- Achiness.

- Bone and/or joint pain.

- Persistent cough.

- Shortness of breath.

- Chest pain.

- Abdominal pain or swelling.

- Feeling of fullness or bloating.

- Headaches.

- Shortness of breath.

- Frequent or severe infections.

- Itchy skin or skin rash.

- Swollen lymph nodes in the neck, underarms, or groin.

- Enlarged liver or spleen.

- Easy bleeding or bruising.

- Recurrent nosebleeds.

- Petechiae (small red spots under the skin).

- Bluish-red tint to the skin.

- Unexplained bone fractures (usually in the spine).

- Difficulty moving parts of the body.

- Weakness or numbness in your legs.

- Increased sensitivity to the effects of alcohol or pain in the lymph nodes after drinking alcohol.

- Anemia (low red blood cell count).

- Leukopenia (low white blood cell count).

- Thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count).

- Enlarged liver or spleen.

- Hypercalcemia (high levels of calcium in the blood).

- Kidney problems.

- Spinal cord compression.

Many blood cancer symptoms can be indicators of other conditions or diseases, including other forms of cancer. Anyone experiencing these symptoms should make an appointment with a doctor to get them checked out.

Diagnosing Blood Cancer

To diagnose blood cancer, a doctor will start by asking about the patient’s medical and family history. Then, they will perform a physical exam, which may include feeling the lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin to see if they are swollen; observing the skin for signs of anemia; and checking for enlargement of the liver or spleen. Based on their findings, the doctor may refer the patient to a specialist, such as a hematologist, for further diagnosis and treatment. Hematologists are doctors who specialize in diseases of the blood.

If the doctor or hematologist suspects a patient may have cancer, they will order more diagnostic blood cancer tests. These may include all or some of the following.

Blood tests: The doctor will likely draw a sample of blood to look for the presence of cancer cells and abnormal levels of red or white blood cells or platelets. Additionally, blood cancer tests may be used to measure liver and kidney function, calcium levels, and uric acid levels, as well as check for certain proteins. Blood coagulation tests may also be done to determine whether the blood is clotting properly.

Urine tests: The doctor may also check for the presence of certain proteins in the urine, as well as levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, albumin, and calcium.

Bone marrow biopsies: The doctor may recommend a procedure to remove a sample of bone marrow from the patient’s hip bone. The bone marrow is removed using a long, thin needle, then the sample is sent to a laboratory where a pathologist will look for cancer cells.

Lymph node biopsies: During this type of biopsy, the doctor removes all or part of a lymph node to see if the cancer has spread there.

Lumbar punctures: Also known as a spinal tap, this procedure may be required to determine the extent of blood cancer. During a lumbar puncture, doctors remove a sample of fluid (cerebrospinal fluid or CSF) from the lumbar area. Lumbar punctures may also be used to inject medications, such as chemotherapy drugs, to treat the disease.

Flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry: These tests are used for immunophenotyping (classifying cancer cells according to proteins on or in the cells). For both types of tests, samples of cells are treated with antibodies (proteins that stick only to certain other proteins on cells).

Imaging tests: Different imaging procedures can provide information about the extent of blood cancer in the body, and the presence of infections or other problems. The following imaging tests may be used to help formulate a blood cancer diagnosis:

- X-rays.

- Computed tomography (CT) scans.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scans.

- PET/CT scans.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

- Ultrasounds.

- 2D echocardiograms (also called multiple-gated acquisition scans).

- Pulmonary function tests.

Staging Blood Cancer

Stage refers to the cancer’s progression, and it affects both the prognosis and treatment options. Most cancers are assigned a numerical stage (usually 1 to 4 or 0 to 4) based on the size and spread of the tumors. However, blood cancer is staged differently, since the disease originates in the blood and bone marrow and usually does not form tumors. Instead, the stages of blood cancer are often characterized by blood cell counts and the accumulation of cancer cells in other organs, like the liver or spleen. Some types of leukemias are not staged at all.

Rather than using traditional staging methods, doctors often factor in the blood cancer type (leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma) and subtype. This often involves many of the same blood cancer tests used to diagnose the cancer. Some of the factors used to stage blood cancer include:

- Presence or absence of symptoms.

- White blood cell or platelet count.

- Age (advanced age may negatively affect prognosis).

- History of prior blood disorders.

- Genetic or chromosomal mutations or abnormalities.

- Bone damage.

- Enlarged liver, spleen, or lymph nodes.

- Presence of proteins in the blood and urine

- Calcium, monoclonal immunoglobulin, hemoglobin, beta-2 microglobulin, and albumin levels in the blood.

Treatments for Blood Cancer

The treatment for blood cancer is tailored to each patient and depends on the type and subtype of cancer, how quickly the cancer is progressing, where the cancer has spread, and the patient’s age and overall health. Blood cancer care teams may include multiple health care specialists, such as primary care providers, hematologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, as well as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and rehabilitation specialists.

Some of the primary treatments for blood cancer include stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and targeted drug therapy. Most patients receive at least one or more of these treatments in combination. Some patients may also be eligible to participate in clinical trials — controlled research studies of new or experimental treatments or procedures that may fall into any of the treatment categories below.

Because some forms of blood cancer are very slow growing, a doctor may decide to delay treatment until the cancer the patient begins to exhibit symptoms. This is called active surveillance. During this period, the patient will be closely monitored and may undergo regular blood, urine, and imaging tests.

When treatment is needed or recommended, it may include one or more of the following treatment options.

Stem cell transplantation: A stem cell transplant, also called a bone marrow transplant or hematopoietic progenitor cell transplant, infuses healthy blood-forming stem cells into the body. Stem cells may be collected from the patient’s own bone marrow or circulating blood (autologous), and/or from donors, such as umbilical cord blood (allogeneic). Before a stem cell transplant for blood cancer, patients usually undergo a conditioning regimen that involves intensive treatment, such as high-dose chemotherapy, to destroy as many cancer cells as possible. Then, they will receive the stem cells intravenously. After entering the bloodstream, the stem cells travel to the bone marrow and begin producing healthy new blood cells in a process called engraftment.

Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy uses anticancer drugs to slow or stop the growth of cancer cells in the body. Chemotherapy for blood cancer sometimes involves giving several chemo drugs together in a set regimen, and it can be administered in pill form, as an injection, or intravenously. Patients may receive chemotherapy alone or in combination with other treatments, such as radiation therapy and stem cell transplantation.

Radiation therapy: Radiation therapy uses x-rays or other high-energy rays to destroy cancer cells, to prevent the cells from spreading, and/or to relieve pain or discomfort caused by enlarged organs or lymph nodes. Radiation is often combined with other blood cancer treatments.

Immunotherapy: Immunotherapy helps stimulate the immune system to better identify and attack cancer cells. A common form of immunotherapy for blood cancer is the use of checkpoint inhibitor drugs, which block signals cancer cells use to hide from the immune system. Another specialized treatment called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy takes the body's infection-fighting T cells, altering them to fight cancer, and infuses them back into the patient’s body.

→ Cancer Patient Sees Total Remission after Clinical trial uses CAR-T cells

Targeted drug therapy: Targeted therapy drugs specifically seek out cancer cells, which can help to reduce damage to healthy cells and reduce the side effects associated with other treatments. Monoclonal antibody therapy uses immune cells engineered in a laboratory. These cells are then injected into the body, where they target specific features in cells to either destroy them or prevent them from growing and spreading.

Dr. Dan Pollyea Breakthrough Story

Latest in Blood Cancer from the Cancer Center

Loading items....

Information reviewed by Dan Pollyea, MD, MS, in July 2025.