Contact UCHealth

Prostate Cancer

Clinical Trials

Make a Gift

What Is Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer occurs when cells in the prostate gland develop changes in their DNA, causing the cells to multiply rapidly. These abnormal cells form a tumor that can destroy normal body tissues and structures. The prostate is a small, walnut-sized gland located behind the base of the penis and below the bladder. The prostate produces seminal fluid, the liquid in semen that protects, nourishes, and helps transport sperm.

Prostate cancer is among the most diagnosed cancers in men. About one in every eight men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer during their lifetime. According to the American Cancer Society, more than 299,010 new cases of prostate cancer are diagnosed in the U.S. each year, resulting in about 35,250 deaths.

In Colorado, there are approximately 4,490 new cases of prostate cancer each year.

Prostate Cancer Prognosis and Survival Rates

Prostate cancer is a serious disease, but most men with prostate cancer do not die from it. Despite this, due to the sheer volume of cases, prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in men in the United States, behind only lung cancer.

Prostate cancer prognosis depends on the type of cancer and the stage at which it is diagnosed. It is usually curable when detected and treated early.

→ An Engineer Tackles the Problem of Prostate Cancer as a Patient and Financial Donor

The five-year survival rate for patients with both localized prostate cancer (where the cancer is still confined to the prostate gland) and regional prostate cancer (where the cancer has spread outside the prostate to nearby structures or lymph nodes) is nearly 100%. About 90% of prostate cancers are local or regional.

The survival rate drops drastically as the cancer spreads beyond the immediate area of the prostate. The five-year survival rate for patients with distant prostate cancer, where the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body, is 32%. This accounts for about 17% of all diagnoses.

Prostate cancer and its treatments may result in complications. Two of the most common are urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Prostate cancer that spreads (metastasizes) can result in damage to organs, and cancer that spreads to the bones can cause pain and broken bones.

Why Come to the CU Anschutz Cancer Center for Prostate Cancer

As the only National Cancer Institute Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in Colorado and one of only four in the Rocky Mountain region, University of Colorado Anschutz Cancer Center has doctors who provide cutting-edge, patient-centered prostate cancer care and researchers focused on diagnostic and treatment innovations.

→ Improving Patient Outcomes in Prostate Cancer

The CU Anschutz Cancer Center also offers a multidisciplinary clinic for prostate cancer patients. Care begins with a preparatory telephone visit with our nurse practitioner, review of pathology and any imaging, and visits with medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, or surgeons based on the needs of the patient. We can often do this entire review in a single day.

Contact the Urology Multidisciplinary Clinic at 720-848-0181.

There are numerous prostate cancer clinical trials being conducted by CU Anschutz Cancer Center members at any time. These trials offer patients options to traditional prostate cancer treatment and can result in remission or increased life spans.

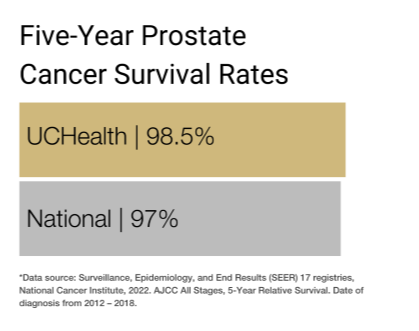

Our clinical partnership with UCHealth has produced survival rates higher than the state average for all stages of prostate cancer.

Types of Prostate Cancer

Different types of prostate cells can become cancerous, and the type of cell affected determines the type of prostate cancer. They are categorized by looking at the cells under a microscope. Doctors use this information to understand the expected growth pattern and speed, as well as which treatments may work best.

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of prostate cancer, accounting for almost all diagnoses. Adenocarcinoma forms in the gland cells of the prostate — the cells that make the prostate fluid that is added to the semen.

Other types of prostate cancer are extremely rare, but they can include neuroendocrine tumors, small cell carcinomas, transitional cell carcinomas, and sarcomas. These rare variants tend to be more aggressive than adenocarcinomas.

Pre-cancerous Conditions That Can Lead to Prostate Cancer

Some cases of prostate cancer may begin as pre-cancerous conditions. Two possible pre-cancerous conditions of the prostate are prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), in which there are changes in how the prostate gland cells look when seen with a microscope, and proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA), in which prostate cells look smaller than normal and there are signs of inflammation in the area.

Although they can be precursors to prostate cancer, many men with PIN and PIA will never develop prostate cancer. However, these men should be followed closely with lab tests, prostate MRI scans, or other biomarkers to help detect cancer.

Risk Factors for Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer has multiple risk factors: behaviors or conditions that increase a person’s chances of getting a disease, such as cancer.

Age: The risk of prostate cancer increases with age. The majority of prostate cancer diagnoses occur in men over 50 years old, and more than 80% of prostate cancers are diagnosed in men 65 or older. The average age at diagnosis is about 66.

Race and ethnicity: For reasons not yet understood, Black men have a greater risk of developing prostate cancer than do men of other races and ethnicities. When diagnosed, Black men are also more likely to die from prostate cancer.

Geography: Prostate cancer diagnoses are more common in North America, northwestern Europe, Australia, and the Caribbean than in other parts of the world. Although increased screening in some developed countries may account for part of this difference, other factors such as diet and exercise may also be contributors.

Family history and genetics: Prostate cancer that runs in families makes up about 20% of all diagnoses. This is due to a combination of shared genes and shared environmental or lifestyle factors. Having a father or brother with the disease more than doubles a man’s risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer, and the risk is even higher for men with several affected relatives. However, most prostate cancers occur in men without a family history of it.

Several inherited gene mutations seem to increase prostate cancer risk, but they account for only about 5% of cases overall. These include hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome, which is associated with mutations to the BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 genes, and Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC.

History of prostate cancer: Men who have already had prostate cancer have a greater risk of developing it again.

Agent Orange exposure: Some studies have suggested a potential link between exposure to Agent Orange, a chemical used extensively during the Vietnam War, and an increased risk of prostate cancer.

Diet: The role of diet in prostate cancer is unclear, but some research suggests that eating a diet that is high in fat, especially animal fat and dairy products, may increase the risk of developing prostate cancer. Other studies have indicated that men who consume a lot of calcium may also be at greater risk. However, most studies have not found such a link with the levels of calcium found in the average diet. Normal calcium intake is still important for other body functions like bone health.

Symptoms of Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer can usually be treated successfully if it is diagnosed before the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body. Patients with early-stage prostate cancer may not experience symptoms, but those with later stages of the disease may experience:

- Uncomfortable feeling or pressure in the pelvic area.

- Frequent urination.

- Slow, weak, or interrupted urinary stream.

- Blood in the urine or semen.

- Trouble getting an erection.

- Bone pain.

- Loss of bladder or bowel control.

- Weakness or numbness in the legs or feet.

- Weight loss.

- Fatigue.

As men age, the prostate enlarges. This can lead to a condition called benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), which is when the urethra becomes blocked. BPH can cause symptoms similar to those of prostate cancer but is not been associated with a greater risk of developing prostate cancer. Men experiencing any of the symptoms above should talk with their doctor.

Screening for Prostate Cancer

Screening is used to look for cancer before a person shows any symptoms of the disease.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends that men between the ages of 45 and 75 discuss prostate cancer screening with their doctor. NCCN also recommends Black men and men with certain genetic conditions get screened as early as 40. Similarly, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends men without prostate cancer symptoms not receive screening if they are expected to live less than 10 years. The ASCO recommends men who are expected to live longer than 10 years discuss screening with their doctor.

The precautionary guidelines around prostate screening are due to possible inaccurate or unclear test results, as well as the potential for overdiagnosis (finding cancer that would never cause problems) and overtreatment (unnecessary treatment of cancer that would never have caused any problems). However, men with additional risk factors, such as Black men and those with a family history of prostate cancer, may decide to get screened anyway.

The most common prostate cancer screening methods are:

Digital rectal examination (DRE): During a DRE, the doctor inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum and feels the surface of the prostate through the bowel wall for any irregularities in the texture, shape, or size of the gland.

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: During a PSA test, blood is drawn and analyzed for PSA, a protein produced by the prostate gland. Elevated PSA levels may indicate prostate cancer, though they can also indicate less-serious conditions, such as infection or inflammation.

These tests may also be performed after a patient has reported symptoms as part of the diagnostic process.

Diagnosing Prostate Cancer

If a doctor detects an abnormality during screenings like a digital rectal examination and a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, they may recommend further tests to determine whether the patient has prostate cancer. Based on their findings, the doctor may also refer the patient to a specialist, such as a urologist. Urologists are doctors who specialize in diseases of the urinary system and male reproductive system.

The only definitive way to diagnose prostate cancer is through a prostate biopsy, but the process may involve many steps, including all or some of the following:

Prostate biopsy: Prostate biopsies are usually performed by urologists. During the procedure, the doctor usually looks at the prostate with an imaging test such as transrectal ultrasound or MRI. Then they collect a sample of prostate tissue using a thin, hollow needle. This is done either through the wall of the rectum (called a transrectal biopsy) or through the skin between the scrotum and anus (called a transperineal biopsy). The doctor will usually take multiple samples from different parts of the prostate. Afterward, the tissue sample is analyzed in a lab to determine whether cancer cells are present.

Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS): During a TRUS, the doctor inserts a small, lubricated probe into the rectum to create an image of the prostate using sound waves. A TRUS is usually done at the same time as a biopsy.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): An MRI scan uses radio waves and magnetic fields to produce detailed images of the body. In some situations, the doctor may order an MRI scan of the prostate to get a more detailed picture. An MRI scan may also be performed at the same time as a prostate biopsy to help guide the needles into the gland. Multiparametric MRI scans can be an accurate way to determine if prostate cancer may be present.

Biomarker tests: A biomarker, also called a tumor marker, is a substance found in the blood, urine, or body tissues of a person with cancer. It is made by the tumor itself or by the body in response to the cancer. Some biomarker tests for prostate cancer include the Prostate Health Index (PHI), SelectMDX, ExoDX Prostate Intelliscore (EPI), and the 4Kscore. Other biomarker tests may also be available.

Stages of Prostate Cancer

After diagnosing the presence of prostate cancer, the doctor will identify the stage of the disease. The stage is determined by several factors, including the PSA level, the Gleason score (see below), and how far it has spread beyond the prostate. The stage impacts both the prognosis and treatment options.

Many of the same tests used to diagnose prostate cancer are also used to identify the stage. Staging may also require additional procedures, such as x-rays, computed tomography (CT or CAT) scans, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) scans, bone scans, and lymph node biopsies.

Doctors usually use the TNM system to determine the stage of prostate cancer. The TNM system assesses the size and extent of the tumor (T-tumor) and whether it has ulcerated; whether the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N-node); and the presence and extent of metastasis (M-metastasis) to distant lymph nodes, bones, and organs.

For prostate cancer, the TNM system also incorporates the patient’s PSA level at the time of diagnosis (determined by a prostate-specific antigen test) and the cancer’s Grade Group, which is an assessment of how likely the cancer is to grow and spread quickly (determined by the results of a prostate biopsy).

Prostate Cancer Grades

The Grade Group is assigned using the Gleason system, which scores the cancer on a scale of 1 to 5 based on how the biopsied tissue samples look under a microscope. Tissue that looks like healthy prostate tissue would receive a grade of 1, and tissue that looks very abnormal would receive a grade of 5, though almost all cancers are grade 3 or higher.

Since prostate tumors often have areas with different grades, grades are assigned to the two areas that make up most of the cancer and then added to form the Gleason score. The first number is the grade most found in the tumor. For example, if the Gleason score is written as 3+5=8, it means most of the tumor is grade 3 and less of the tumor is grade 5. They are added together for a Gleason score of 8. Although the Gleason score can technically range between 2 and 10, cancers rarely score below 6.

Prostate cancers are divided into three groups based on their Gleason score:

- Cancers with a score of 6 or less are called low-grade or well differentiated.

- Cancers with a score of 7 are called intermediate-grade or moderately differentiated.

- Cancers with scores of 8 to 10 are called high-grade or poorly differentiated.

In recent years, doctors have begun assigning a Grade Group to prostate cancers based on their Gleason scores.

- Grade Group 1 = Gleason 6.

- Grade Group 2 = Gleason 3+4 = 7.

- Grade Group 3 = Gleason 4+3 = 7.

- Grade Group 4 = Gleason 8.

- Grade Group 5 = Gleason 9 or 10.

The higher the Grade Group, the more likely the cancer is to grow and spread quickly. The CU Cancer Center’s pathologists are some of the best in the country at assessing prostate pathology. We also do second-opinion reviews as a routine part of our practice.

Prostate Cancer Stages

After the TNM assessment, the doctor will assign an overall stage number from 1 to 4. These can be broken down further based on the size of the original tumor and the extent to which the cancer has spread. In general, the lower the stage the better the prognosis and treatment options.

Stage 1: The tumor is confined to one-half of one side of the prostate or less. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or other parts of the body. The Grade Group is 1 and the PSA level is low.

Stage 2: The tumor is confined to the prostate. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or other parts of the body. The Grade Group is between 1 and 4 and the PSA level is low to medium.

Stage 3: The tumor may have grown outside the prostate to the seminal vesicles, urethral sphincter, rectum, bladder, or the wall of the pelvis. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or other parts of the body. The Grade Group is between 1 and 5 and the PSA can be any level.

Stage 4: The tumor may have spread beyond the prostate to nearby lymph nodes and may have also metastasized to distant lymph nodes, structures, or bones. The Grade Group can be any value and the PSA can be any level.

Treatments for Prostate Cancer

The treatment for prostate cancer is customized to each patient and depends on the size of the tumors, the stage at which the patient is diagnosed, and the patient’s general health. Prostate cancer care teams may include multiple health care specialists, including primary care providers, urologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, as well as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and rehabilitation specialists. CU Cancer Center doctors offer specialized care for patients with prostate cancer.

Treatments for localized prostate cancer are surgery, radiation, cryotherapy, and high-intensity focused ultrasound. In patients where the cancer has spread beyond the prostate, doctors may recommend systemic treatments such as hormone therapy, targeted therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and bone-modifying drugs. Patients may receive one or more of these treatments in combination. Some patients may also be eligible to participate in clinical trials — doctor-led research studies of new or experimental procedures or treatments.

Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer

Patients with early-stage and low-grade prostate cancers may not require immediate treatment, and some never require it. Because prostate cancer treatments can cause side effects like erectile dysfunction and incontinence that may seriously affect a person's quality of life, many doctors and patients decide against immediate treatment.

Instead, they may opt for active surveillance. During active surveillance, the doctor may perform regular PSA urine tests, digital rectal exams, imaging tests, and prostate biopsies to monitor the progression of the cancer. Active surveillance may also be the best option for men with other serious health conditions or whose age makes cancer treatment more difficult or risky.

Surgery for Prostate Cancer

The most common surgery to treat prostate cancer is called a radical prostatectomy. During this procedure, a surgeon removes the entire prostate, the seminal vesicles, some nearby lymph nodes, and some of the tissue around the prostate to ensure no cancer cells are left behind.

Radical Prostatectomies:

There are two main types of prostatectomy. In an open prostatectomy, the surgeon operates through a single long incision in the skin. In a laparoscopic prostatectomy, the surgeon makes several small incisions and uses special surgical tools to remove the prostate, either manually or through the use of robotic arms. Most radical prostatectomy operations are now performed laparoscopically and robotically using the daVinci robot.

Open prostatectomies:

In a radical retropubic prostatectomy, the surgeon makes an incision in the lower abdomen, from the belly button down to the pubic bone.

In a radical perineal prostatectomy, the surgeon makes an incision in the skin between the anus and scrotum (the perineum). However, this operation is rarely done and cannot remove lymph nodes.

Laparoscopic prostatectomies:

In a laparoscopic radical prostatectomy, the surgeon inserts special long instruments into several small incisions in the abdomen. One of the instruments has a small video camera on the end to let the surgeon see inside the body.

In a robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy the surgeon sits at a control panel in the operating room and moves robotic arms to operate through several small incisions in the abdomen. This approach is also known as robotic prostatectomy. This is how most prostate operations are performed now.

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP):

During a TURP, the surgeon removes the inner part of the prostate gland that surrounds the urethra. This surgery is primarily used to treat men with non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate (also called benign prostatic hyperplasia, or BPH). But it may also be used in patients with advanced prostate cancer to mitigate symptoms, such as trouble urinating. TURP is not used to try to cure the cancer.

During a TURP, an instrument called a resectoscope is passed through the tip of the penis into the urethra up to the prostate. Electricity is then passed through a wire to heat it or a laser is used to cut or burn away the tissue.

Bilateral Orchiectomy:

Bilateral orchiectomy is the surgical removal of both testicles. It was the first treatment used to treat metastatic prostate cancer more than 70 years ago, but it is rarely used today. Although it is a surgery, bilateral orchiectomy is considered a form of testosterone-suppression therapy, as it removes the main source of testosterone production, the testicles. This is done rarely and only in men where the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer

Radiation therapy uses high-powered energy to kill cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in radiation therapy to treat cancer is a radiation oncologist. The two main types of radiation therapy used to treat prostate cancer are external beam radiation and brachytherapy.

External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the most common radiation treatment and uses a machine located outside the body to focus a beam of x-rays on the area with the cancer. This type of radiation is most often used to treat earlier stage prostate cancers or to relieve symptoms from later stage prostate cancers, like bone pain.

Brachytherapy, or internal radiation therapy, involves the insertion of radioactive pellets — each about the size of a grain of rice — directly into the prostate. These pellets, also called seeds, give off radiation only around the area. High-dose brachytherapy may be left inside for a short amount of time (less than 30 minutes), which low-dose brachytherapy is left in for a longer amount of time (up to a year). Brachytherapy may also be referred to as seed implantation or interstitial radiation therapy.

In some situations, a doctor may recommend both types of radiation therapy.

Cryotherapy for Prostate Cancer

Cryotherapy, also called cryosurgery or cryoablation, is a type of focal therapy. Focal therapies are minimally invasive treatments that destroy small prostate tumors without affecting the rest of the prostate gland. Cryotherapy for prostate cancer involves freezing and killing cancer cells with a metal probe inserted through a small incision in the area between the rectum and the scrotum. Cryotherapy is a relatively new treatment and is not yet considered a frontline therapy for men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. However, it may be used to treat patients with low-risk, early-stage prostate cancer who cannot have surgery or radiation therapy or in cases where the cancer has come back after radiation therapy.

High-intensity Focused Ultrasound for Prostate Cancer

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is a heat-based focal therapy. During this procedure, an ultrasound probe is inserted into the rectum and sound waves are directed at any tumors on the prostate gland, heating the tissue and destroying the cancer cells. HIFU was approved by the FDA for the treatment of prostate tissue in 2015, and doctors are still determining the best use cases for it.

Hormone Therapy for Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer cells rely on male sex hormones (androgens) to grow. Lowering the levels of these hormones can help slow the growth and spread of prostate tumors. Testosterone — the most common androgen — can be lowered by surgically removing the testicles (bilateral orchiectomy or surgical castration) or taking drugs that turn off the function of the testicles (medical castration).

Another way to stop testosterone from encouraging cancer growth is a type of medication called an androgen axis inhibitor, which either stops the body from making testosterone or stops testosterone from working. Abiraterone, enzalutamide, and apalutamide are some of the medications that can be helpful in men with advanced prostate cancer.

Hormone therapy is commonly used to treat advanced prostate cancer to shrink the cancer and slow its growth. It may also be used to shrink tumors and improve the effectiveness of radiation therapy.

These treatments may also be referred to as testosterone-suppression therapy, androgen-suppression therapy, or androgen-deprivation therapy.

Targeted Drug Therapy for Prostate Cancer

Targeted therapy focuses on the specific genes, proteins, or tissue environments that contribute to prostate cancer, limiting damage to non-cancerous cells and tissues.

The most common targeted drug therapies for prostate cancer include:

Olaparib (Lynparza) is a PARP inhibitor. It is approved for patients with metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer who have homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene defects. These gene defects make it harder for cancer cells to repair damaged DNA. Certain genes, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, are linked with HRR gene defects.

Rucaparib (Rubraca) is another PARP inhibitor approved for patients with metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer who have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation that is either inherited or found within the tumor.

Targeted therapy drugs are usually recommended to treat advanced or recurrent prostate cancer in cases where hormone therapy has not worked.

Chemotherapy for Prostate Cancer

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill rapidly growing cancer cells. Although chemo is not a standard treatment for early prostate cancer, it may be used to treat tumors that have not responded to hormone therapy or that have spread outside the prostate to other areas of the body.

Chemotherapy for prostate cancer can be administered in pill form or through a vein. This type of chemo is called systemic chemotherapy, because the drugs enter the bloodstream and attack cancer cells anywhere in the body. Standard chemotherapy for prostate cancer usually begins with docetaxel (Taxotere) combined with the steroid prednisone. Another chemo drug, cabazitaxel (Jevtana), is used to treat metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer that has already been treated with docetaxel.

Immunotherapy for Prostate Cancer

Sometimes the body's immune system does not attack cancer because cancer cells produce proteins that help them hide from immune system cells. Immunotherapy, also called biologic therapy, boosts the patient’s immune system to help it attack and destroy cancer cells.

Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) is a prostate cancer vaccine. Unlike traditional vaccines, which encourage the immune system to help prevent infections, this vaccine enhances the immune system to help it attack existing prostate cancer cells. The vaccine is produced for each specific patient, and though it is not a cure for prostate cancer, clinical trials suggest that the vaccine may lengthen the lives of patients with advanced prostate cancer by about four months.

Another immunotherapy approach to prostate cancer is the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors or checkpoint blockade therapies — drugs that target the body’s checkpoint proteins, helping restore the immune system’s natural defenses against cancer cells. Checkpoint inhibitors can be used for patients whose prostate cancer cells have tested positive for certain gene changes, including changes in one of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes or a high level of microsatellite instability (MSI-H). Both of these genetic conditions are frequently seen in patients with Lynch syndrome.

Bone-modifying Drugs for Prostate Cancer

Doctors may use specific drugs to treat or relieve pain in patients with prostate cancer that has spread to the bones or to lower the risk of bone fractures related to certain prostate cancer treatments.

Radiopharmaceuticals are drugs that contain radioactive elements. Radiopharmaceuticals are administered by a radiation oncologist or nuclear medicine doctor through intravenous injection and deliver radiation particles directly to the prostate cancer tumors that have spread to the bones. The most common radioactive drugs used to treat prostate cancer spread to bone include Radium-223 (Xofigo), Strontium-89 (Metastron), and Samarium-153 (Quadramet).

Testosterone suppression therapy can cause or worsen bone conditions like osteopenia and osteoporosis. Patients receiving hormone therapy should be evaluated for risk of bone fractures, and those who are found to have an increased risk should receive treatment to lower that risk. Bone-modifying drugs that may address these issues include denosumab (Prolia and Xgeva), zoledronic acid (Reclast and Zometa), risedronate (Actonel), alendronate (Fosamax), ibandronate (Boniva), and pamidronate (Aredia).

Some studies suggest that corticosteroids such as prednisone and dexamethasone can help relieve bone pain, including in men with prostate cancer that has metastasized to the bones. These drugs may also lower PSA levels.

Latest in Prostate Cancer from the Cancer Center

Loading items....

Information reviewed by Paul Maroni, MD, in August 2022.