Making Central Line Infections Nearly Disappear

By Dan Meyers

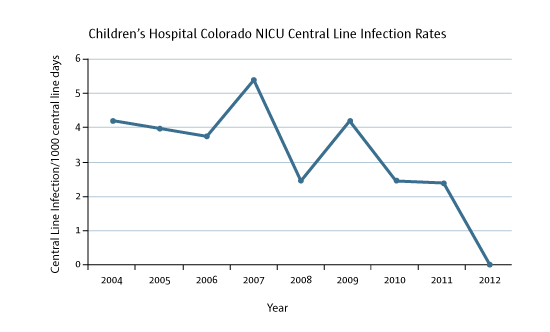

A few years ago, the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Children’s Hospital Colorado recorded a central line infection every two weeks or so.

A few years ago, the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Children’s Hospital Colorado recorded a central line infection every two weeks or so.

In the last nine months, the NICU has had one.

“None of us ever anticipated getting to this point,” says Susan Dolan, RN, the hospital epidemiologist.

The sweeping improvement in central line infections came about through a widespread hospital effort that, as Dolan notes, exceeded expectations and was achieved not through fancy medical machinery but with small, vital steps.

To understand what happened, let’s go back about three years. The hospital was looking at its central line infection rates, which are tracked by state and nationally.

“We recognized the rates were fairly high, although we thought perhaps they were appropriate because with the hospital’s capabilities we might get the tougher cases,” says Theresa R. Grover, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics and medical director of the NICU.

The NICU, a high-performing part of a hospital consistently ranked among the top 10 pediatric hospitals nationally, decided to lead an effort to knock that rate down

“We didn’t think the infections were completely preventable,” Grover says. “We never thought we would get rid of nearly all of them.”

Central lines—typically a peripherally inserted central catheter, or PICC line—are used to deliver antibiotics, nutrition and

The hospital knows a central line infection is likely to keep a child in the hospital longer, require antibiotics and cost perhaps an additional $40,000 for care. Infection is a risk factor for poorer neurological outcomes, especially in preterm babies. A bloodstream infection in the NICU increases the odds of the baby getting meningitis, Grover says.

Children’s began assessing. The hospital found that some basic steps could make a difference, such as:

Hand-washing before and after every contact with a patient. “Secret shoppers”—incognito observers—were deployed to see what the reality was and the staff made this basic step an even higher priority.

Cleaning the catheter properly and consistently. Was everyone doing it right, prior to accessing the central line? They set a standard: Scrub the hub of the catheter for 15 seconds with alcohol and friction and wait for it to dry before entering the central line

Children’s also stepped up efforts to detect infections, so staff could catch problems earlier. And the hospital made it a team thing; everyone pitched in and set high goals.

“We had accepted for so long that some of the infections were just part of our unit,” Dolan says. For example, two-thirds of the infections were in babies with altered intestinal linings, mostly from intestinal failure, resulting in bacteria getting into the blood. “We thought we could never get rid of those,” Dolan says.

The result of the new steps kicking in? A 40 percent reduction in central line infections in the first year.

Then Children’s joined a group of 25 pediatric hospitals working on quality improvement and sharing ideas.

The infection rate dropped again. From mid-November 2011 to last July it was zero. Since July, one (as of CU Medicine Today press time).

Where does Children’s go from there?

Other ICUs within the hospital are adopting those procedures or similar ones. Dolan and the epidemiology team scour hospital infection data daily. Home care nurses receive the same training to address infections outside the hospital and to reduce readmissions. Hospital staff work with parents on prevention steps such as hand washing and proper line care in the home setting.

They also began writing it down for staff to easily see progress. On a board outside the staff lounge, the number of days since the last infection is posted. Nobody wants to be the one to break the streak.

“Now,” Dolan says, “it’s about sustaining it.”