Coffee's Link to Heart Health

CU researchers grind through the data

By Mark Couch

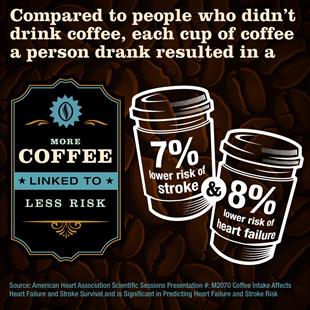

(May 2018) A cup of coffee a day might not keep the doctor away, but an extra cup or two could keep the cardiologist at bay.

Investigators from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus recently presented research that shows drinking coffee is linked

Just don’t ask if coffee is a magic elixir to will let you live longer.

“This was the main question we received: ‘Should I drink more coffee to live longer?’” said David Kao, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Cardiology. “I don’t think you can take it quite that far because we don’t know whether it’s the coffee itself or something else.”

Kao and Laura Stevens, a doctoral candidate in the University’s computational biosciences program, were invited to present their findings at the annual scientific meetings of the American Heart Association (AHA) last December.

While they can’t say conclusively that drinking coffee extends your life, they were able to show that drinking coffee is associated with a lower risk of some serious life-limiting conditions.

According to their review of data collected in the Framingham Heart Study, which has tracked the eating patterns and cardiovascular health of more than 15,000 people since the 1940s, they found that every extra cup of coffee consumed per day reduced heart failure by 5 percent, and stroke by 6 percent.

The news perked interest around the globe, with reports in the International Business Times in London, Time magazine, and in the online pages of the “the voice of Clarksville, Tennessee.”

“Everybody drinks coffee,” Kao said. “It’s a high impact idea that a lot of people can relate to. Plus, it validates what a lot of people had hoped would be true – that more coffee is better. It justifies their behavior. I figured that that would resonate.”

Stevens and Kao explained that grinding through the data is a massive project that required “machine learning” to identify associations that would be buried under the multiple possible connections between numerous variables.

Machine learning is a way of getting computers to recognize patterns and make predictions, rather than simply executing pre-programmed tasks. It’s teaching the computers to discover or ‘learn’ new patterns within large amounts of data, and it works the same way that online shopping sites aim to predict a shopper’s preferences based on previous purchases or an email provider tries to separate spam from other messages.

“What machine learning allows us to do is to identify factors that may be important when we don’t know what we’re looking for in large pools of information,” Kao said.

“In this

Their study of the Framingham data confirmed that certain well-known factors – such as smoking and high cholesterol – had

While the machine learning process found that coffee may be important for predicting heart disease, it didn’t establish a connection to increased or decreased risk of getting the disease. It simply showed that coffee was in the top 15 percent of important factors among the hundreds of factors poured into the mix.

“Once you have an idea that coffee is important at predicting risk, what you don’t know from machine learning is whether it is associated with increased risk or decreased risk, so from there we used more traditional methods to evaluate if coffee drinking was harmful or protective,” Stevens said.

“Once you have an idea that coffee is important at predicting risk, what you don’t know from machine learning is whether it is associated with increased risk or decreased risk, so from there we used more traditional methods to evaluate if coffee drinking was harmful or protective,” Stevens said.

“In this

While coffee consumption was associated with the decreased risk, the study doesn’t show a cause and effect relationship.

“This specific data analysis doesn’t give you that,” Stevens said. “And that’s what we’re looking into now. We are curious if it is some other habit that people who drink coffee have that is related, or if it is the caffeine or the antioxidants in the coffee itself?”

To check their results, Stevens, Kao and their colleagues used traditional analysis in two other studies with similar sets of data – the Cardiovascular Heart Study and the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities Study. The association between drinking coffee and a decreased risk of heart failure and stroke was found in all three studies.

Now that the AHA presentation has been completed, Stevens and Kao are working on drafts of papers on the work.

“I think the tricky part is where to stop with this first paper because people want to go all the way down the rabbit hole and you just can’t take on everything at once,” Kao said. “So that’s where we are right now is trying to decide where to stop with this presentation with an eye toward what happens next.”

The importance of the study wasn’t just the finding

“Our findings suggest that machine learning could help us identify additional factors to improve existing risk assessment models, said Stevens, who is a data scientist for the Precision Medicine Institute at the AHA. “The risk assessment tools we currently use for predicting whether someone might develop heart disease, particularly heart failure or stroke, are very good but they are not 100 percent accurate.”

Stevens conducts research seeking to connect genetic information to lifestyle, environmental, and clinical factors.

“I think the kind of work that Laura did is the next wave in personalized medicine,” said Kao, who is a member of the Colorado Center for Personalized Medicine. “There are so many things that could be important, that you could modify, that you can’t study in the way we’ve studied medicine in the past.

“This was an interesting result in and of itself, but as just interesting is that the method can work and find novel information in other datasets that are important to people, and that may represent a potential intervention, positive or negative. I think without that personalized medicine is going to be very hard to pull off.”