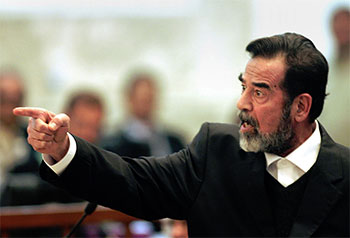

Caring for Saddam Hussein

Alumnus Joseph Horam treats former Iraqi director

Tonia Twichell

(May 2017) By 2006, a desert deployment did not faze Col. Joseph Horam, MD.

(May 2017) By 2006, a desert deployment did not faze Col. Joseph Horam, MD.

Horam had already deployed twice to the Middle East, including serving in Saudi Arabia during Desert Storm. After he transitioned from the active Army in 1994 and joined the Wyoming National Guard, he assumed deployments abroad were behind him.

“I thought ‘That’s the last I’ll see of this. That’s the once-in-a-20-year event,’” said Horam, a 1987 graduate of the CU School of Medicine. “Little did I know this kind of deployment would be recurring.”

When Horam received a call in early spring 2006 asking him to come a month early to Iraq, he was experienced enough to suspect a high-level assignment was in the cards.

Upon arrival in Baghdad, the commander of special missions asked if he’d like to learn more about his new patient, VIC.

“Vic?”

Very Important Criminal, aka Saddam Hussein.

At that point, the former Iraqi dictator had been in custody for three years, facing multiple charges of crimes against humanity and a likely death sentence for atrocities that included the massacre of more than 140 people in the town of Dujail after an assassination attempt in 1982.

Horam arrived in Iraq at a particularly fraught moment. The Abu Ghraib torture and abuse scandal, in which members of the U.S. Army and Central Intelligence Agency committed a series of human rights violations against detainees and which led to the deaths of at least two people, remained in the news.

“Memories of the atrocities were fresh. I learned that Saddam was to be kept in optimal health to allow for justice to prevail – or the show could go down,” he said. “No pressure!”

Horam knew the job overseeing the health of the combative former dictator would be far more complicated than ordering lab tests, reviewing medicine and performing physicals.

Care included building trust, which meant smoking cigars together in the evening, enduring Hussein’s rage when Horam wouldn’t help mediate a pardon for

Hussein’s charisma was notable, but Horam knew not to put much stock in it.

“I always recognized him for being a brutal dictator.”

Always in a Medical Setting

A lifetime of patient care had prepared Horam for this unusual assignment. His father, an Army supply sergeant, had encouraged his son to join the military after graduating from Hinkley High School in Aurora. But Horam had his own ideas.

He worked at a packing plant, in construction

Familiarity with the medical profession prompted him to enter CU’s Child Health Associate/Physician Assistant Program in 1974. In 1983, he joined the CU School of Medicine with the U.S. Army Health Profession Scholarship Program. A pediatric residency made sense to him because he grew up with two brothers who each had a severe form of quadriplegic cerebral palsy.

“What I realized over time is that I was always in a medical setting while growing up with my brothers.”

In Desert Storm, he was assigned to a hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where he recalls that Iraqis received most of the trauma care because they were poorly equipped for battle.

During Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2004, Horam, now a member of the Wyoming National Guard where he was the Medical Detachment Commander and State Surgeon, was deployed to Balad, Iraq, where helicopters filled with injured soldiers arrived for treatment.

“Day to day we saw routine cases and severe trauma. It exposed me to things I wanted to be able to experience and assist with.”

Being a pediatrician was never an obstacle.

“When you look at the statistics, about 40 percent of soldiers are 24 years old or younger. Plus, pediatricians are pretty good with infectious disease, mental health and comprehensive team management of complex patients.”

While there, he again had medical encounters with enemy combatants.

“Regardless who comes in, there is a moral obligation to provide humane care. You’re not going to win hearts and minds. That’s not going to happen when you take care of the enemy. You do it because it’s the humane thing to do.”

Treating Saddam Hussein

Hussein’s body had taken a beating over the years, and treatment included care for old shrapnel wounds, hypertension with adrenal adenoma and other issues common for a 67-year-old man.

Hussein’s body had taken a beating over the years, and treatment included care for old shrapnel wounds, hypertension with adrenal adenoma and other issues common for a 67-year-old man.

Upon arrival, Horam was handed a foot-tall stack of papers documenting Hussein’s medical care under coalition forces.

Horam also cared for several members of Hussein’s cabinet, many other high-level detainees, and U.S. soldiers at Golby Troop Medical Clinic. But as Horam expected, the forceful, narcissistic former dictator had a way of insisting he was patient No. 1.

“He knew I was going to be his advocate for his medical care. But he started believing that I was also his advocate for his personal agenda.

One thing I never bought into is that I would become sympathetic for his cause.”

Hussein was proud of his accomplishments as the country’s leader, often talking about improvements to the country’s education, military, government, medical care

Hussein knew that the U.S. was struggling in Iraq, and he believed he could serve as a mediator and leader in a new government.

“His agenda was basically that he was the one person to lead his country. He was willing to do it in partnership with the U.S. government. Ultimately he was angry with me for not having the level of influence to get the political and military leadership to meet with him and bring his issues forward.

“He threatened to fire me at least three times.”

To show his frustration with his American captors and the Iraqi court proceedings Hussein went on two hunger strikes – the first was brief, the second was 19 days long.

Horam’s concern was Hussein’s mental condition. “There was a point when he was less energetic, and the thing you have to realize is that we were coming up on the latter part of his court hearings. We risked acquittal if he appeared weak and in less than optimal health.”

Horam decided he needed some assurance that Hussein was not in danger of starving himself to death, so he asked a psychiatrist on staff for a set of questions.

“We needed to make sure we were not in a situation where his competency was compromised. So I asked the questions and the psychiatrist analyzed the answers. His opinion: It was not a hunger strike to the death. It was a hunger strike for protest and behavior manipulation.”

At that point, Horam was living in the prison that housed Hussein and his former cabinet, and he felt the heavy burden of his responsibility. “I was always a little more intimidated by the process than by my patient.”

While there were always guards nearby, Horam was often alone with Hussein and the other incarcerated detainees.

“I did feel at times that if he had a weapon of choice, he would not have hesitated

But there were quieter moments. Hussein liked to host his American captors for dinner and Cuban cigars, which were provided by the Red Cross.

“He talked about his family and religion. He was interested in different philosophies, and sometimes just liked to sit and listen to our discussions when we would talk about our own issues. He could be very contemplative.”

Hussein often wrote poetry and read Hemingway, Horam said. Sometimes he would gather with his former cabinet.

“When they would get together he was in his element. He was still in charge.”

Horam once asked Hussein about U.S. intelligence reports during the first Gulf War that indicated Iraqi forces were prepared to use Scud missiles armed with chemical warheads against U.S. troops. In response, hospitals had been set up and 12,000 beds readied for casualties.

“I asked Saddam what actually happened in Desert Storm when we were getting pretty high alerts about chemical threats. He said, ‘There

Keeping a Secret

Horam left Iraq about four months before Hussein’s execution. Their parting was respectful.

Horam left Iraq about four months before Hussein’s execution. Their parting was respectful.

Horam introduced Hussein to his new

For 10 years Horam kept quiet about his patient due to non-disclosure restrictions imposed by the military. He returned to his medical practice at Cheyenne Regional Medical Center, grateful for partners who had cared for his patients during

He still thinks about the man he now describes as his “eeriest patient ever.”

A few years ago, he was at a gathering with other physicians, some of whom had also cared for Hussein during his incarceration. Horam’s wife, Carol, was talking with the other wives.

“One of the other spouses came over and said, ‘You never told Carol about being Saddam Hussein’s doctor?’”

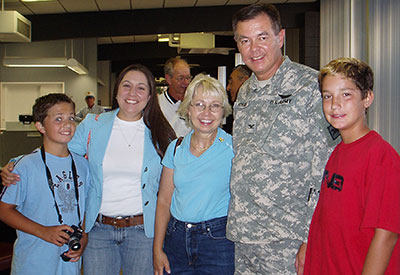

Carol Horam wasn’t upset about being kept in the dark, but, with a laugh, Horam said she now understands why he didn’t call home to talk with her and their three children very often during that particular deployment.

Plus, “Carol always knew there was more to my story about receiving a Bronze Star,” he said.

Horam has since retired from the military after 27 years of service and has a lifetime of stories about his adventures abroad.

“I miss it,” he said. “I really do. I would do it again. The experience gave me a sense of purpose and allowed me to fulfill service to state and nation as a medical officer assigned to the U.S. Army that was unique.

“I felt I did an excellent job as a military doc.”