John Farrington Donates Priceless Book Collection

.jpg?sfvrsn=fb309db8_2)

By Melanie M. Sidwell

(May 2016) A recent gift of precious books to the CU School of Medicine by alumnus John Farrington, MD ’52, offers a glimpse at just how far medical knowledge has advanced.

Last fall, Farrington donated five rare books, published between 1676 and 1896, from his private collection to the School “that changed my life,” he says.

One, an X-ray machine manual published in 1896, was handed down from Farrington’s father. Two other books — textbooks published in the 19th century about diphtheria and human physiology — were given to Farrington by a former patient.

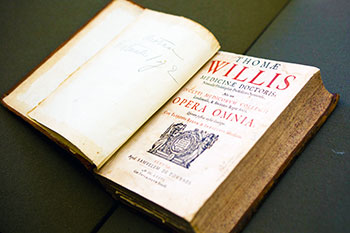

The other two texts, both published in 1676, came to Farrington from an elderly Irish neighbor named Thomas O’Shea. “The two oldest books have a real history,” Farrington says.

Farrington and O’Shea would sit on the front porch swing of his Boulder home, having conversations that opened young Farrington’s eyes to a wider world. But when Farrington was 8 years old, O’Shea moved to Florida to escape the Colorado winters.

Before he left, the Irishman gave Farrington a gift: two human anatomy books by English physician Thomas Willis that O’Shea said he purchased at a market in Mexico City.

Before he left, the Irishman gave Farrington a gift: two human anatomy books by English physician Thomas Willis that O’Shea said he purchased at a market in Mexico City.

Farrington kept the

After serving in the U.S. Army, Farrington — like his father and grandfather before him — became a physician.

“I started as a medical student in 1948 with white knuckles because I got in as an alternate — I found out on a Friday that I was going to medical school on Monday,” Farrington says. “I was concerned because I wanted to do well. But the reality was that medical school was the easiest part of my education because it was what I wanted to do, and I had the bent for it. The CU School of Medicine gave me the opportunity to do it.”

After graduation, Farrington completed a fellowship at the Cleveland Clinic. In 1956, he established his practice in Boulder and served as assistant clinical professor of medicine at the CU School of Medicine until 1987. In addition, Farrington developed the first intensive and critical care pulmonary medicine program at Boulder Community Hospital — the first at a community hospital in Colorado — where he taught his fellow doctors and nurses about respiratory care.

Through the years, Farrington has received numerous honors for his commitment to CU, including the Medical Alumni Association’s Silver and Gold Award, the George Norlin Award, the Board of Regents Medal, and the University Medal for Distinguished Service Award. He is also a past president of the School of Medicine Alumni Association and the CU-Boulder Directors Club. An active member of CU alumni associations since the early 1960s, Farrington continues to further the vision of the university. He, along with other classmates, helped to establish the Class of 1952 Scholarship Endowment.

.jpg?sfvrsn=8f3f9db8_2) “His latest gift to CU — that curious menagerie of texts — are in good hands at the Health Sciences Library,” which houses more than 112,000 books and 30,000 e-journals, says Deputy Director Melissa De Santis.

“His latest gift to CU — that curious menagerie of texts — are in good hands at the Health Sciences Library,” which houses more than 112,000 books and 30,000 e-journals, says Deputy Director Melissa De Santis.

Farrington’s donated books, which can be seen by appointment, will be kept in a climate-controlled, secure vault.

“If books fall apart, nobody can use them,” says Emily Epstein, a cataloging librarian at the Health Sciences Library. “We lose information about what physicians knew about diseases and medical treatment at the time, and there’s also evidence we find in margins like signatures or notes.

There is data to be mined from it.”

Despite all the medical advances that have occurred since these historic books were published, some aspects of being a physician never change, Farrington says.

“If you don’t know where you’ve been, you don’t know where you’re going. It’s important for medical students to know their ancestry as physicians and see the evolution of medicine,” he says. “But some of the skills of the old clinicians are still valuable. The stethoscope is still important. You need to learn to sit and talk to people and put them at ease — treat them like they are the only patient you’ve got, and for the moment you have them in front of you, that’s true.”