Don Bennallack Delivers

Faculty Profile

By Jim Spencer

At some point in their labor or delivery, most of Don Bennallack’s patients heard these words: “You’re going to meet somebody today who you’ve never met before, who you will love as much as anyone you’ve ever loved in your life.”

At some point in their labor or delivery, most of Don Bennallack’s patients heard these words: “You’re going to meet somebody today who you’ve never met before, who you will love as much as anyone you’ve ever loved in your life.”

Dr. Bennallack’s summation of parenthood was uncanny given that he never fathered any children. At the same time, the retired obstetrician, who graduated from the University of Colorado School of Medicine in 1950, felt a kinship with every baby he delivered. All 3,366 of them. Bennallack also practiced gynecology for 36 years.

But in his words, “I liked delivering babies more than taking out people’s uteri. I was transfixed by two little cells making an individual.” Collectively, those individuals turned out to be the family he never had.

So did one particular colleague. “My father passed away in 1998,” says Denver pediatrician Jodie Mathie. “I got married in 2000. So he [Bennallack] walked me down the aisle.”

Mathie met Bennallack in 1984, when he began

Bennallack was so dedicated that Mathie says he delivered “some second-generation babies”—children of the children he delivered decades earlier.

“Every baby was a pleasure,” he says. “I love being part of people’s lives.”

It wasn’t that Don Bennallack, the son of a Denver cop and a graduate of the city’s East High and CU-Boulder, didn’t want his own kids. It just never worked out.

But in effect, he married medicine and squired her through decades of private practice.

“I liked people,” he says simply. “I felt a part of many families, even though I didn’t have one.”

Bennallack lives where he has for the past

Overcoming a glut of Ob-Gyns

After serving in the military, he opened his Denver practice in 1959; Bennallack waited six weeks to see his first patient. She turned out to be a referral from the Colorado Medical Society. Earlier, a fellow ob-gyn had informed him curtly that Denver already had more than enough doctors with his specialty.

“I did flight physicals at Lowry Air Force Base for $4 an hour,” Bennallack says. “I gave the CU School of Nursing lecture on sex education.”

Bennallack was used to doing whatever it took to make ends meet. The military put him through part of

Bennallack was used to doing whatever it took to make ends meet. The military put him through part of

“I had to fix a finger that had been cut off,” he says. “I had to pull teeth and pull dislocated bones back into sockets. You know, the simple stuff, because I wasn’t a doctor yet.”

He retired in 1995. The debt that today’s medical students bear inspired Bennallack to donate his estate to the CU Foundation.

“When I buy the farm,” he says, “what I have is going to help medical students.”

He already helped pay the way through medical school for the son of a friend. There are others who “would make good doctors if they got some help,” he says. Bennallack knows what it takes to be a good doctor.

His sister, Pat, 16 years his senior, ran his office and joined every exam.

“I always believed that when you are a male obstetrician and gynecologist, you should have another female in the room when you examine patients,” Bennallack explains.

Bennallack liked his sister so much that he waited until she died in 1988 to grow the long hair and goatee he’d always wanted.

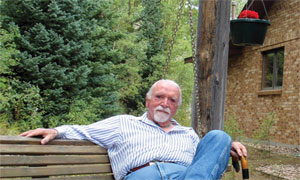

Today, at 85, his ponytail and beard are white. He was diagnosed with skin cancer in 1996, forcing surgery and chemotherapy. Now, as an octogenarian, he wants to live out his life in peace.

“I feel good,” Bennallack says. “I’ll go to the doctor when I don’t feel good.”

Celebrating a good life

For now, he chooses to travel the world with friends,

“His eyes were still black and blue from the operation,” Mathie says. “But as I would do a wonderful party for him, he did one for me.”

These days, Bennallack wraps himself in the spiritual intimacy of his mountain property, with lovely memories.

“I feel the house takes me in its arms and protects me from the outside world,” Bennallack says.

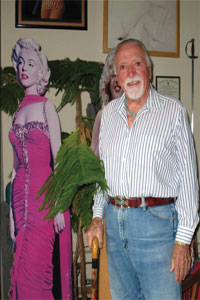

He savors the views and entertains occasional visitors who stay in a guesthouse decorated with a museum’s worth of Marilyn Monroe memorabilia. Life-size cutouts, photos, posters, calendars, wine bottles,

The Marilyn Monroe craziness began when Bennallack accompanied one of his employees, Kim Kerr, to a costume party in the mid-1980s. Kerr went as Marilyn, Bennallack as Joe DiMaggio. From then on, when Bennallack would have medical residents he mentored over to his mountain home to celebrate the end of their service, they would bring Monroe memorabilia. Then, his neighbors and friends got in on the gag.

Bennallack isn’t sure what will happen to this collection when he “buys the farm,” but if it’s worth anything, he knows the students at his alma mater will benefit from it.