Teaching Medical Ethics and the Holocaust

By Tonia Twichell

(May 2016) In 2013, the Liaison Committee for Medical Education polled all medical schools in North America to find out how many require students to learn about the role of physicians in the Holocaust.

(May 2016) In 2013, the Liaison Committee for Medical Education polled all medical schools in North America to find out how many require students to learn about the role of physicians in the Holocaust.

The answer: 22 of 140, a dispiriting number to some University of Colorado faculty members who had requested the question be included in the annual survey.

In a June 2015 letter to journal Academic Medicine, Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, director for the CU Center for Bioethics and Humanities, William Silvers, MD, and Jeremy Lazarus, MD, wrote, “… it appears that the specific attention to arguably the most influential set of events in the history of professional ethics in medicine is required at only a fraction of U.S. and Canadian medical schools – and this despite a uniform requirement to teach ethics and professionalism.”

They knew there was interest in the subject. Silvers, who was involved in organizing a series of seminars on medicine and the Holocaust in the Denver area starting in 2008, says overflow crowds attended some of the presentations at Anschutz Medical Campus.

When Wynia came to CU three years ago, he and Silvers collaborated to continue the program on campus. In October 2015 Silvers pledged $100,000 to kick-start the CU Holocaust Genocide and Contemporary Bioethics program. All three physicians were involved in its creation.

“I always felt a personal responsibility to not lose the lessons that should have been learned in the Holocaust,” says Silvers, whose parents were survivors of the camps. His mother was liberated from Auschwitz, his father from Dachau. “I especially felt strongly about the role of medicine since I am in medicine.”

Wynia became involved in Holocaust education while working as the director of the Institute of Ethics at the American Medical Association and was asked by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum to collaborate on a program around the museum’s Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race exhibit.

“I have an interest and a passion to better understand physicians who become killers,” Wynia says. “What is the path to evil? These are people who are sworn to uphold human dignity and to pursue the well-being of people they take care of. Despite that, they become entirely perverted. What’s more, there are research abuses that take place in the U.S. Why is it that it doesn’t become widespread?”

The program’s seminars will incorporate other historic genocides as well as more recent abuses like the Tuskegee syphilis study (1932-72) and health professional involvement in prisoner torture in Abu Ghraib and elsewhere. But the clearest example of medical complicity in genocide is the Holocaust, which Silvers calls the “sentinel genocide of Western society for our generation.”

The program’s seminars will incorporate other historic genocides as well as more recent abuses like the Tuskegee syphilis study (1932-72) and health professional involvement in prisoner torture in Abu Ghraib and elsewhere. But the clearest example of medical complicity in genocide is the Holocaust, which Silvers calls the “sentinel genocide of Western society for our generation.”

“In almost every arena of medical ethics there is some feature or often the core that was influenced by the Holocaust,” Wynia says. “All of the big issues today and the way we think about them are influenced by this history. It’s distressing not having this information included as part of a student’s education.

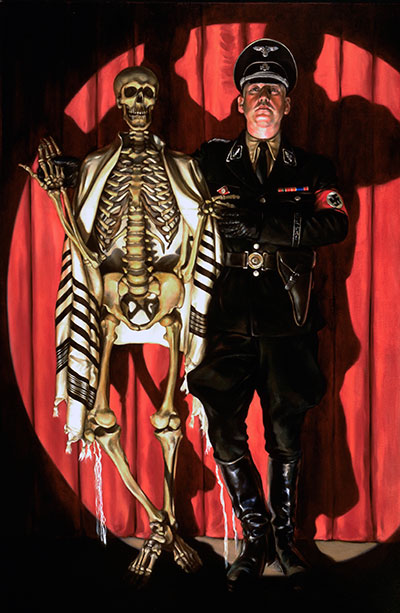

Most people don’t know the extent of participation by health care professionals during the Nazi regime.

“What people know about medicine and the Holocaust usually extends to (German physician and SS captain Josef) Mengele and his medical research abuses,” Wynia says. “His crimes aren’t the most important thing to understand. What Mengele did – that’s what happens after things have already gone way too far.”

The physicians would like the seminar information eventually to be included in interdisciplinary courses on campus.

Meanwhile, they will encourage students and campus professionals to attend Holocaust program seminars to learn the relevance of the Holocaust in their own careers. Seminars in early May featured bioethicist and author Art Caplan,

“There were medical heroes in the camps, but not as many as you’d hope,” Wynia says. “Of all those people who performed ‘rampe’ duty at Auschwitz (the process of selecting who would live and who would go to the gas chambers), of all the doctors, nurses and dentists, just one person is known to have refused. A physician. And he was not punished. That leads one to wonder, ‘What if many had said no? What if the medical profession had stood up?’”

Silvers hopes students take the lessons to heart.

“I want them to have an appreciation of