Sometimes Things Line Up Just the Way They Are Supposed to

By Mark Couch

(November 2014) That’s how Dean Richard Krugman, MD, describes his decision earlier this year to announce his plan to step down when a new dean is hired to lead the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Well, those are not the exact words he used. Instead, his description was a bit more Krugmanesque—serious and playful, creative yet cosmic.

“It was a syzygy,” he says. “You know what a syzygy is? No? S-y-z-y-g-y. Things came together. A syzygy is an unusual alignment of several things that don’t normally align that way.”

For more than two decades, the sun rose in the east, flowers bloomed in the spring, snow fell on the mountains, the Broncos and Rockies took the field and Richard D. Krugman, MD, was the dean of the School of Medicine. That’s just how things were meant to be.

As the longest-serving dean in the history of the School of Medicine and currently the longest-tenured leader of any medical school in the United States, Krugman has earned the nickname “Dean of Deans.”

“He really is the gold standard of medical school leadership,” says Lilly Marks, University of Colorado’s vice president of health affairs and executive vice chancellor of the Anschutz Medical Campus. “Dick provides a model of integrity, trust and collaboration.”

And that tenure lends tremendous value to the entire institution, says CU President Bruce Benson.

“He has a huge national reputation,” Benson says. “He’s been here as dean for over 24 years, and that helps the School of Medicine, the Anschutz Medical Campus and the university. It’s a huge deal to have somebody with his stature.”

During his more than 24 years at the helm of the School of Medicine, he has presided over an era of unprecedented growth and prestige for the venerable institution by nurturing careers, mentoring colleagues and building a team of physicians and scientists who are training a generation of new leaders in research and medicine, and providing world-class care to patients.

In the 24 years before he became dean, the School of Medicine had 11 different deans or acting deans, and five of those had served in the decade preceding Krugman’s appointment as interim dean in 1990.

Since becoming dean, more than 4,000 physicians, physician assistants, physical therapists and medical scientists have earned degrees from the school and launched their careers.

Krugman has appointed all department chairs, major center directors and senior leadership at the school; established a workplace that values collaboration; directed the school’s move to the nation’s newest academic medical center campus; and strengthened the school’s financial foundation by overseeing the growth of its successful physician practice plan, University Physicians, Inc. (UPI).

He manages an enterprise that has a $1.1 billion annual budget and more than 3,000 faculty members who practice medicine at five affiliated health care providers and other sites across the state and around the world. UPI this year reported annual revenues of $609 million, its best year ever, extending an unbroken string of more than 20 consecutive years with double-digit percentage growth.

And then last year, Krugman saw the syzygy. Family matters, scholarly goals and professional accomplishments had aligned to tilt his orbit in a new direction.

“From the family perspective, we have seven grandchildren who live thousands of miles away, and they’re all getting older,” he says. “They range in age from 7 months to nearly 16 years. We have only been able to be with them on weekends during the year. It would be nice to spend a longer period of time with the far-flung members of our family. And they really are far-flung. They are in Boston, Baltimore, Atlanta and Tokyo.

“It’s awkward to be like a helicopter grandparent. I always have meetings on Friday until at least noon, and I always have meetings at 8 o’clock Monday morning. And that means when they are that far away, you only get to see them on Saturday and Sunday—and only half the day Sunday. And that’s just not enough time to spend with family.”

Research that Krugman long dreamed of doing also remains undone and he figures the time is now.

“Professionally, I was on my way to do a study and try to make some major changes in the child abuse field in 1990 when I got into this job,” Krugman says. “I put off a sabbatical at that time to become acting dean because I thought it would only last a year or two. Interestingly, the problems I was trying to work on in that field are still there 24 years later, and I think I’d like to have the next phase of my career be just a professor working in the area that is pretty important for me.”

Krugman, who was director of the Kempe Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect from 1981 to 1992, is one of the nation’s leading experts on the subject, and his plan was always to compare how some European nations handle such cases with to the American system.

During his career, he has published more than 100 papers, chapters and editorials, and four books on the subject. He served as chair of a U.S. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council committee that last year released a major report finding that efforts to prevent, identify and respond to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States remains undersupported, inefficient, uncoordinated and unevaluated.

“The child protection system in the United States is still struggling,” Krugman says. “The approach that this country has taken to try to help abused children and their parents wasn’t working in 1990, and I don’t see any evidence that it’s working any better now. And the systems I wanted to study in Europe, for the most part, are still there, although they’ve changed some. But neither system has any data to support their assertions that they have good outcomes. And from my perspective that’s part of what needs to be done in the field of child abuse.”

Time marches on—or Krugman might say, “the great conveyor belt of life never stops”—so Krugman decided he’d better get to Belgium.

“I got a call at the Kempe Center from the chancellor, Bernie Nelson, who said, ‘The dean has resigned. I need to talk to you about who should be acting dean. Could you stop by the house?’ So I stopped by his home on the way home and

I brought him three names.”

“I got a call at the Kempe Center from the chancellor, Bernie Nelson, who said, ‘The dean has resigned. I need to talk to you about who should be acting dean. Could you stop by the house?’ So I stopped by his home on the way home and

I brought him three names.”

Nelson asked Krugman to be dean, but Krugman demurred. “I said, ‘Well, I can’t do this job because I’m going to Belgium.’”

And so began a back-and-forth dance that lasted for more than a year.

On July 5, 1990, Krugman became acting dean, and three months later Nelson asked him to take a three-year contract as dean. The university’s president, the Board of Regents and the chancellor were all pleased with his performance and wanted to make it permanent.

“I said, ‘I appreciate the support, but I’ve always believed that if your only support is above you, you’re hanging. So, why don’t you start a search and if the chairs and the students and the faculty think I should be in the job after a search, I’m happy to consider the job, but I’m not going to just take the job.’

“So they started a search and I didn’t apply.”

Krugman still was planning to go to Belgium and was preparing a major national meeting in Denver on child abuse issues. But after an intervention by the search committee and some faculty, he says he was convinced to apply for the job as dean.

Meanwhile, school leaders were preparing a retreat in December 1991 on how to solve the turnover in the dean’s position. Between 1978 and 1990, prior to Krugman’s appointment, there had been six acting, interim and permanent deans of the medical school.

“I missed that retreat because I wound up in the hospital with appendicitis,” Krugman says. “I had an emergency appendectomy on the night of Dec. 16, 1991, and when I woke up the next morning, among other people at my bed was the chancellor who said he’d gotten my name from the search committee and he wanted to negotiate. And I said, ‘That’s nice, but I don’t negotiate on morphine. I’ll see you after the first of the year.’”

For the first two months of the year, Krugman negotiated the deal, and on the last day of February, he was called to Nelson’s office where he found his wife Mary, a few other people, a cake and a final offer letter.

“I remember taking the letter, turning around, going outside, reading it again and then coming back in and saying, ‘What the hell,’ and I signed it. And so on March 1, I had my acting-ectomy after my appendectomy.”

There were those who were concerned: “My father, who was chair of pediatrics at NYU, called me every week and said, ‘What the hell are you doing? That is a terrible job—the dean job. Are you OK?’

“And I’d say, ‘You know, Dad, I’m fine. It’s kind of interesting,’” Krugman says. “You know, I’d basically spent my whole life in pediatrics and with pediatricians. And I actually thought everybody was like pediatricians. It turns out they’re not and that’s why 90 percent of physicians are not pediatricians! So if you’re interested in human behavior, this is a terrific job to see the diversity and the power and the problems of human behavior.”

Krugman says he recognized he had a gift for administration.

“I guess I never believed that this was a job I would ever want. I mean some people desperately want to be chairs or deans or presidents, and I never really wanted to do that. I was very happy doing what I was doing.

“Now, I happen to enjoy administration. I’ve been administering things since I was the captain of the crossing guards of P.S. 50 in the fifth grade and when I was chief resident in pediatrics. Administration isn’t something I hate. I find it not so hard. I’m interested in people and in institutions and in human behavior.”

And all those years learning about how societies handle child abuse and neglect proved to be good training, Krugman says. Dealing with groups that have diverse points of view but are working for a common good proved to be great training for the top job at the medical school.

“I’ve said this before and people always sort of laugh or don’t understand it,” Krugman says. “Being in child abuse work for 10 years was really good preparation for this job because in that work you have to work with physicians, lawyers, social workers, law enforcement, criminal and civil judges, educators. They all think differently, they all solve problems differently. They all see life from their own perspective, and if you’re going to be successful on behalf of the child and the family, you need to be able to work as a multidisciplinary team. You need to listen and take what they say into effect.

“It turns out that schools or universities are not very different. And in this environment, it’s not just all of the faculty and the departments, but it’s five different hospitals, it’s different health systems, it’s alumni, it’s the legislature, it’s everybody who’s got a different perspective on what the job is. They are made up of all these very different groups of people, but the analogue to the child and the family is that if this school and the university are going to be successful, you have to make sure that all of its parts work well together.”

And not everything was easy over the years.

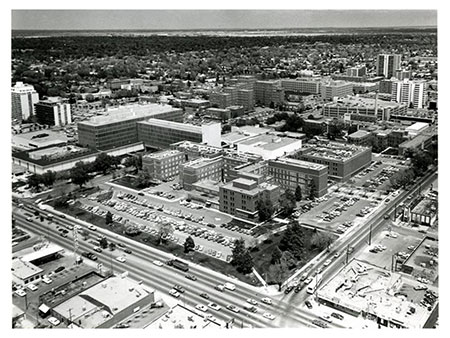

The momentous decision to move away from the Ninth Avenue Campus in Denver to the abandoned former Fitzsimons Army garrison in Aurora was divisive and difficult. When Chancellor Vincent Fulginiti told Krugman that the university was moving, Fulginiti

estimated it would take 20 to 30 years to make a full transition to a new campus because he expected to depend on state funding for the construction.

The momentous decision to move away from the Ninth Avenue Campus in Denver to the abandoned former Fitzsimons Army garrison in Aurora was divisive and difficult. When Chancellor Vincent Fulginiti told Krugman that the university was moving, Fulginiti

estimated it would take 20 to 30 years to make a full transition to a new campus because he expected to depend on state funding for the construction.

“I remember clearly saying to him, ‘Vince, if this takes 20 to 30 years to move, then the medical school will move last. Don’t bother to call me for the planning.’”

Krugman explains that he himself needed to be convinced that the move was a good idea. It was only after Lilly Marks and others showed how the faculty could facilitate the move by dedicating a portion of their administrative funding from grants to cover construction costs that it became clear that most of the move could occur by 2012.

“It is true that not everybody was in favor of it,” Krugman says. “The Department of Medicine in particular and the basic science chairs didn’t want to be disrupted. They felt if we built one more research building on the Ninth Avenue Campus that would do it. That would serve our needs.”

Other options were considered. The school looked at possible construction on the west side of Colorado Boulevard, but the neighborhoods and city leadership were opposed.

“The other opportunity we had in 1994 was we were offered 55 acres in Lowry when it closed,” Krugman says of the former Air Force base. “But the city wanted $6.5 million for it and we didn’t have the $6.5 million. And, by the way,

it was the best $6.5 million we never had.”

The Lowry site was too small to accommodate all the growth of the school, let alone leave space to attract Children’s Hospital Colorado to locate on the same campus as the school.

The Lowry site was too small to accommodate all the growth of the school, let alone leave space to attract Children’s Hospital Colorado to locate on the same campus as the school.

“We would have sent all of the health services research to Lowry, Children’s would still be downtown, we’d have 400 to 500 faculty downtown, we’d have 100 to 200 faculty there [at Lowry], we’d be trying to maintain three campuses. It would have been awful,” he says.

The failing conditions of the older buildings at the Ninth Avenue Campus helped change some minds about moving to Fitzsimons.

“I remember the day that Boris Tabakoff came to see me. He was the chair of pharmacology and one of the sewage pipes between the second and third floor burst and dumped sewage into his radioactive phosphorus hood where he was doing an experiment. And he got the basic science chairs together and he came down to my office and he said the basic chairs will move.”

Krugman’s approach to managing the move was in his distinctive style, says Marks.

“So many people interpret leadership as ‘follow me up the hill; I’m going to lead you into battle,’” Marks says. “Dick established a sense of trust and created an environment that allowed people to do incredibly bold things without having a revolution. He built a team that was a real team and he empowered them. He was very generous in allowing them to do things and he didn’t try to steal the spotlight.”

The result led to the construction of a campus that is a major engine of the Colorado economy. A report released this summer found that the CU Anschutz Medical Campus infused $2.6 billion in direct spending into the state economy in the fiscal year ending June 30, 2013, and supported 21,954 jobs.

Sustaining the school and the campus is an ongoing concern for leaders. Federal budget cuts are restricting grant funding, and national efforts to control health care spending will affect clinical income.

“We are, compared to a lot of other medical schools, very under capacity for how much clinical activity we can have here, and I think with the new campus and the success of these two hospitals [University of Colorado Health and Children’s

Hospital Colorado] we have the ability to really rebrand ourselves,” Krugman says. “And I think this can be a destination campus—like a Texas Medical Center, like Mayo, Cleveland and others—in the future if we really pay attention

to that, and that’s really where the revenue comes from to support your research and education and community service missions.”

The Krugman Legacy

Dean Richard Krugman, MD, and his colleagues reflect on his near quarter-century at the helm of the School of Medicine.

Watch the video →