Lung Transplant Patient Overcomes Long Odds

Tony Hammes improves with care at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital

By Todd Neff

(October 2018) When Tony Hammes developed a cough that stuck around longer than he thought it should, he went to a doctor in November 2010 to have it checked out.

Antibiotics didn’t do much, nor did rounds of steroids and other treatments. Years passed and Hammes moved from Illinois to Wisconsin to Colorado. Ultimately he was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The air sacs in Hammes’ lungs were like “stacks of red grapes, except the

The condition was noticeable but manageable. Hammes might become winded more quickly than he did in the past, but he could still do the things he liked to do: play sports with his son Jonah, enjoy the outdoors with wife Kristin, play golf with friends and colleagues, work in the yard.

Breathing becomes more difficult

“Here we are, married 20 years, and you’re with a guy with one of those big old-person tanks,” Hammes said to his wife.

“Here we are, married 20 years, and you’re with a guy with one of those big old-person tanks,” Hammes said to his wife.

He continued to travel for work, toting the largest portable oxygen concentrator airlines allow in a cabin. But by December 2016, it was clear that Hammes needed a lung transplant.

He had already started pulmonary rehabilitation, but now it was about keeping himself in the best possible shape prior to surgery. Still, his lungs got worse. At home, he relocated to the guest bedroom on the first floor to avoid climbing stairs.

On Sept. 1, 2017, after driving Jonah to school, he called the UCHealthLung Transplant Center and was advised to come in. It would be the beginning of a long, eventful stay.

A team of pulmonologists including Crossno, Todd Grazia, MD, associate professor of medicine, and Marty Zamora, MD, professor of medicine, focused on Hammes’ case. They stabilized him, but by September 7, Hammes’ lungs could no longer do the job, no matter how much supplemental oxygen he received.

He would need to rely on extracorporeal membrane

Life-saving technology

Muhammad Aftab, MD, assistant professor of surgery, performed that surgery. Coming out of it, half-inch-thick clear tubes resting in part on Hammes’ head carried his blood. Between bites of a peanut butter sandwich, Hammes remarked to Crossno: “This is really cool.”

Crossno recalled that he begged to differ: “I’m like, ‘Tony, this is not cool.’”

Here’s why: ECMO might be a life-preserving technology (or “really cool” as Hammes describes it), but relying on it could cause Hammes to be dropped from the transplant list. Crossno and the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH) team were concerned.

A lung transplant patient must be able to expand the chest and walk at least a bit.

Hammes’ survival hinged on the right pair of lungs arriving in the nick of time. He knew

That way of thinking also applied to Hammes’ wife and son, who, he told himself, “will be strong enough themselves, and have a strong enough support system, to go on without me.” Hammes’ optimism made his room in the UCH Cardiothoracic ICU popular among providers.

So did the unicorns.

Using an app on his phone, Hammes gave unicorn names to doctors, nurses, and others, based on the first letter of their name and their month of birth. Hammes’ unicorn name, “Prince Blueberry,” ended up under his actual name on the whiteboard in his room. Keeping the theme, friends from work brought a unicorn statue to his ICU room.

Transplant success

Lungs arrived just in time. Michael Weyant, MD, professor of surgery, performed the surgery on September 26. Hammes spent another month in the hospital, the last stop being the rehabilitation unit, where each day he had two sessions each of occupational and physical therapy. In late October, he was home again.

Lungs arrived just in time. Michael Weyant, MD, professor of surgery, performed the surgery on September 26. Hammes spent another month in the hospital, the last stop being the rehabilitation unit, where each day he had two sessions each of occupational and physical therapy. In late October, he was home again.

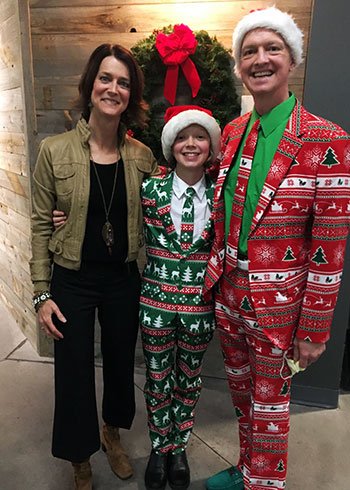

Lung transplant recovery takes time. But by February, with help of concerted pulmonary rehabilitation, he was shooting baskets with Jonah, now 13, and by early April he was working nearly full-time.

“We’re still in the honeymoon period, but he’s doing well,” Crossno said. “We really pulled that one out of the fire.”

For Hammes, he is here just as he had hoped and on some level expected. He says he’s grateful beyond words – for the donor and his family; for his own family and friends; for his colleagues at O’Neal Flat Rolled Metals; and for the skillful, personally engaged care he received at UCH from the doctors to the nursing staff, the ECMO specialists and the respiratory, occupational and physical therapists.

“I’ll probably get emotional about

He maintains a sense of wonder about the UCH Transplant team that saved him.

“What happened is incredible. It’s incredible that people have dedicated their lives to learn and become experts at this so people can benefit from it,” he said.

Hammes visits the ICU after most of his outpatient appointments, to say hi and to thank them again. He wears a surgical mask as Crossno and colleagues suggested.

On a recent visit, a certified nursing assistant who didn’t recognize him behind the mask asked if she could help him.

“I used to live here for a couple of months,” he said. “You might have taken care of me.”

She searched his face.

“I’m Tony,” Hammes said. “I’m the unicorn guy.”

Her face lit up. “Prince Blueberry!” she said.

A version of this article appeared in the UCHealth Insider in May 2018.