A Stoke Patient Battles Back at UCH

By Tyler Smith

(November 2016) Jim Cohen lay motionless in bed, aware that something was terribly wrong. He couldn’t move. His brother Howard was close by, but Cohen couldn’t cry out for help. His mind was active, but his body was locked in paralysis.

(November 2016) Jim Cohen lay motionless in bed, aware that something was terribly wrong. He couldn’t move. His brother Howard was close by, but Cohen couldn’t cry out for help. His mind was active, but his body was locked in paralysis.

What began as a Labor Day weekend visit to Howard’s home in Basalt and a planned trip to Telluride to watch films had taken a terrible turn. A clot had choked the flow of blood to his brain stem, the outlet for electrical signals to the rest of his body. In essence, Cohen, 60, had suffered a devastating spinal cord injury while lying in bed.

Time became a stream that flowed through a landscape without references. In his mind, Cohen called out to Howard. At some point he wondered if he’d died. He saw himself visiting with his grandmother and a cleaning lady from his past as a young man in Buffalo, N.Y. In a dream, he suggested to his wife Connie that they go out for lunch. Then they were in a restaurant, but Cohen couldn’t breathe.

He hadn’t felt well the previous couple of days, including the drive to Howard’s house. He’d had intermittent vision problems and thrown up the evening he arrived. Howard figured he’d let him sleep. When he finally discovered Cohen in a desperate state, Howard summoned an ambulance that rushed his brother to Valley View Hospital in Glenwood Springs. The deadly blood clot remained lodged in the brain.

Fighting for a friend

The weekend was also to take a turn for Ben Honigman, MD, an emergency medicine physician at University of Colorado Hospital and associate dean of clinical outreach at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Honigman and his wife had flown to Denver International Airport the Friday before Labor Day, returning from vacation. When he checked his cell phone, he saw a series of texts from Howard with the shocking news of the stroke. Jim couldn’t communicate, his brother told Honigman. What can we do?

The question called for the dispassionate clinical analysis needed to save a life, but Honigman felt a far greater sense of urgency. The man lying motionless in Valley View’s emergency unit had been Honigman’s close friend for more than 30 years. They had met when Cohen and his wife Connie began making their mark together in the restaurant business in Denver. At an art exhibit opening Honigman attended, he was introduced to Cohen and the two began talking. They went out with a group for sushi afterward. When another artist began talking about cooking as a craft, not an art, Cohen engaged him in “an enormous fight,” Honigman recalled.

It didn’t come to blows, but it was close. The sparks that night ignited a long conversation and an enduring friendship between Honigman and Cohen. They learned they shared similar Rust Belt upbringings – Honigman’s in Youngstown, Ohio, aligning with Cohen’s in Buffalo. Now,

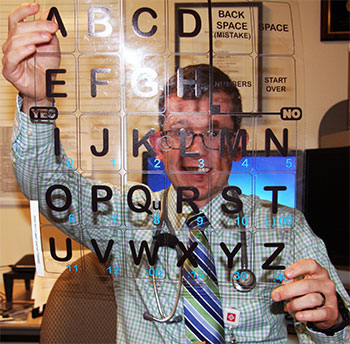

William Niehaus, MD, a physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist, shows the type of letter board Cohen used to communicate in the days after his stroke.

Honigman knew, the stroke threatened to end Cohen’s life or leave him profoundly disabled. Honigman ultimately arranged for Cohen to be flown to UCH for treatment and what he considered a “slim chance” of survival.

Shades of gray

In a procedural suite at UCH, neurosurgeon Joshua Seinfeld, MD, looked at images that showed a complete blockage of Cohen’s left vertebral artery, which supplies blood to the brain stem and left occipital lobe. It had been 14 hours since the clot

shut down the artery – a dangerously long period of time. Seinfeld used a stent retriever to pull the blood clot out of the artery, but his work wasn’t finished. The vessel was badly diseased and still couldn’t accommodate much blood

flow. Seinfeld performed a balloon angioplasty to widen it.

In a procedural suite at UCH, neurosurgeon Joshua Seinfeld, MD, looked at images that showed a complete blockage of Cohen’s left vertebral artery, which supplies blood to the brain stem and left occipital lobe. It had been 14 hours since the clot

shut down the artery – a dangerously long period of time. Seinfeld used a stent retriever to pull the blood clot out of the artery, but his work wasn’t finished. The vessel was badly diseased and still couldn’t accommodate much blood

flow. Seinfeld performed a balloon angioplasty to widen it.

The stroke damage was extensive, said Seinfeld, assistant professor of neurosurgery. Describing Cohen’s case later, he pointed to bright areas on an image of Cohen’s brain – signs of a “completed stroke” that left dead tissue. Had there been more of it, the clot-removal and angioplasty procedures wouldn’t have happened, Seinfeld said.

“Restoring blood flow to dead brain tissue will cause a hemorrhage,” he said. “In [Cohen’s] case, it was risky to remove the clot, and we knew he could do poorly, but if we left it alone, he would die. When there is an occlusion in the areas of the brain where he had his stroke, we tend to consider treatment for a longer period of time than for strokes at the top or the front of the brain because people can have a [much better] response.”

The images of Cohen’s brain showed areas of distinct light and dark – the clearly defined lines of tissue life and death. But there were also shades of gray, areas where the two intersected. Those patches defined the uncertainty that awaited Cohen after Seinfeld finished the procedure.

Choosing yes

Sharon Poisson, MD, co-medical director of the Stroke Program at UCH and associate professor of neurology, had the difficult job of explaining to Cohen and his family what had happened and what to expect. She told them that Seinfeld’s work had prevented the stroke from getting worse and that Cohen might show some improvement over time. But she couldn’t be certain because of the site of the stroke, a relatively small area of the brain with an outsized measure of control over the rest of the body. Ultimately, Cohen might not be able speak, swallow or regain his independence, Poisson said.

“The problem with a brain stem stroke is that it occurs in an expensive piece of real estate,” she said. It also has less plasticity, or ability to respond to change, than other areas of the brain, she said.

Cohen, meanwhile, was alive and cognizant, but he was “locked in,” able to communicate at first only by blinking – once for “yes,” twice for “no,” and then with very slight head nods. His sister, Nancy Carlson, MD, a pediatrician in the Denver area, explained what was happening to him as he lay in a Neuro ICU bed at UCH. He felt Nancy was encouraging him, but in fact she was in emotional turmoil.

“It felt hopeless,” she said. “I was concerned we were saving him for nothing.” It was hard to imagine her brother consigned to life on a gastric tube. Cohen was no ordinary chef. In 1983, Julia Child had selected him as one of the top 11 chefs in the country and flown him and the others to Santa Barbara, Calif., for a week of filming for her PBS show “Dining with Julia.” He went on to a career that established him as one of the nation’s top chefs and culinary innovators. Now Nancy pondered the cruel irony of Cohen living life as a chef who couldn’t swallow.

Poisson reconvened the family at his bedside. She told Cohen that he would need a tracheotomy and a gastric tube to survive, at least in the short term, and underscored again the uncertainty of what lay ahead for him.

Cohen’s response was to agree to the practical things necessary to keep him alive. He blinked once for a tracheotomy and one more time for a feeding tube.

“I was very pessimistic,” said Honigman, who was there when Cohen made the decision to move forward. “I felt that anything positive that came out of it would be miraculous.”

Honigman wasn’t alone in reaching that conclusion. Fearing there wasn’t much time left, the boyfriend of Cohen’s daughter came into the ICU to ask Cohen for his blessing before proposing marriage.

Cohen blinked once.

Signs of life

William Niehaus, MD, a physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist with UCH and instructor of physical medicine and rehabilitation, came by the Neuro ICU to see Cohen four days after the surgery. Cohen was far from in the clear, said Neuro ICU Medical

Director Robert Neumann, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurosurgery. He was on blood thinners to protect against another clot forming and vasopressors to keep his blood pressure stable and perfuse his brain stem. The blood thinners and vasopressors,

however, also increased Cohen’s risk for a bleeding stroke, Neumann said. He characterized Cohen’s condition as providing only “a flicker of hope.”

William Niehaus, MD, a physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist with UCH and instructor of physical medicine and rehabilitation, came by the Neuro ICU to see Cohen four days after the surgery. Cohen was far from in the clear, said Neuro ICU Medical

Director Robert Neumann, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurosurgery. He was on blood thinners to protect against another clot forming and vasopressors to keep his blood pressure stable and perfuse his brain stem. The blood thinners and vasopressors,

however, also increased Cohen’s risk for a bleeding stroke, Neumann said. He characterized Cohen’s condition as providing only “a flicker of hope.”

Against this solemn backdrop, Niehaus dug into Cohen’s medical chart and emerged with an optimistic view.

“Not many people appreciate how good the quality of life can be for people who are locked in,” Niehaus said. He met with Cohen’s family in the solarium of the ICU, pointing to the possible. Cohen had strong family support. There were assistive technologies and equipment to help him communicate, move, and perform daily activities, even if he never was able to do more than move his eyes.

Niehaus spoke of focusing on “the next five minutes” rather than the enormity of the injury. The recovery, wherever it led, would come in stages: from the ICU to a med/

“Dr. Niehaus told us not to make decisions about Jim’s care too quickly,” Connie said. “He was cheerful, optimistic and inspirational. I give him credit for keeping our family going when things were bleak.”

Niehaus was not offering false optimism. “Jim was as impaired as it gets,” he said. “His stroke hit an area of his brain where everything plugs in and interfaces with the rest of the body.” But Cohen was “cognitively intact,” Niehaus added, and made progress moving and communicating in small but important increments – from eye blinks to eyebrow raises and slight head nods.

To help Cohen express his thoughts, Niehaus and speech therapists brought in a clear plastic sheet with letters and simple words. Cohen fixed his eyes on a letter, while a partner holding the sheet – often Nancy or Honigman – moved their eyes until they locked with Cohen’s. In this way, he slowly and silently formed words and sentences.

“The eye movement with the board became our form of communication for several weeks,” Honigman said. He and Nancy had a friendly competition to see who could decipher Cohen’s thoughts the quickest.

While he was in the Neuro ICU, Cohen also drew inspiration from a visit by a hospital volunteer, himself a stroke survivor. Cohen can’t remember who it was, and he couldn’t speak at the time, but he vividly recalls the message.

“He spoke with me and my family,” Cohen recalled. “He said, ‘That was me 18 months ago.’ It gave me a lot of encouragement. I thought, ‘If he can do it, I can do it.’”

A new chapter

With time and practice, Cohen was able to move his left arm and leg, crucial advancements toward his goal of getting to Craig Hospital to continue his recovery. It wasn’t a slam dunk. Cohen had to show a liaison from Craig who came out to UCH that he could tolerate three hours of intense physical, occupational and speech therapy every day while sitting in a wheelchair.

After nearly three weeks at UCH, including a stint on the Neurosciences Unit, Cohen was discharged, becoming one of the rare patients locked in by a stroke that Craig accepted for rehabilitation. He slowly regained his ability to speak and left Craig feeling “pretty good” on his left side and with new computer skills that make use of optical technology, just as Niehaus had said. He followed that with a 100-day stint at Quality Living, Inc. (QLI) in Omaha, a comprehensive center that focuses on helping patients with severe brain and spinal cord injuries regain as much independence as possible.

It was a lonely time, Cohen said, but he felt he had to do it. “The hardest part of this is asking people to help you,” he said. “I wanted my family and my friends to get back to their lives and not feel obligated. It’s hard on people.”

He persevered with the help of FaceTime, a commitment to his rehab regimen and a determination to improve QLI’s cuisine.

“The food there was so bad,” said Cohen, a not surprising observation from a guy with high culinary standards. On a 15-day visit, Connie took him to Whole Foods to get the ingredients he wanted for a revamped menu.

The effort gave Cohen another source of motivation. His contribution also paid off for QLI and Cohen’s fellow patients. “They loved having a chef there to teach cooking,” Connie said.

Cohen left QLI in April moving with the help of a walker, talking more freely, eating and “mentally with it,” as Honigman put it. He’s now walking short distances with a cane and doing some cooking with the help of Connie and his occupational therapist. His daughter Lexi runs the Empire Lounge and Pizzeria da Lupo, which he opened in Louisville and Boulder in 2008 and 2010, respectively, but his commitment to cooking remains.

“Every part of my brain works,” he said. “I teach people.”

Between the darkness and the light

The reasons for Cohen’s journey back from the edge of death aren’t easy to explain. Honigman readily admits that Cohen’s story, inspirational as it may be, offers no blueprint for others who suffer the same kind of stroke and receive the same expert care.

“Everyone is different,” Seinfeld said.

For Poisson, Cohen’s is “a standout case,” but not simply because of the positive outcome. She saw him while he lay in a netherworld, his body nearly inert, his mind active.

“He was a motivated patient with a motivated family,” Poisson said.

Cohen continues his recovery with that support and by tapping into his competitiveness and his will to succeed.

He illustrates this point with a telling story. Just out of the ICU, he said, he overheard a visiting childhood friend say that Cohen would be better off dead.

“We did everything when we were young together,” Cohen said. “We went to school, walked neighborhoods, and ran paper routes. We were competitive. I credit him with my drive.”

After he heard his friend’s words, Cohen had a simple response: “Screw you.”

It’s a combativeness that led to professional success.

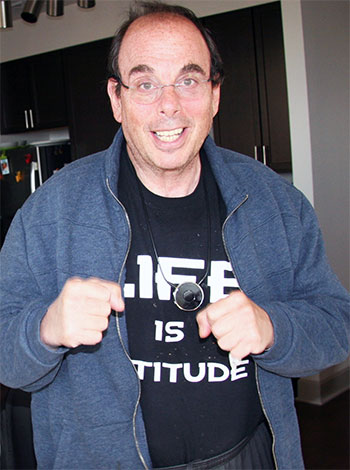

“When I would meet other chefs, my attitude was, ‘You’re no better than I am. I just need to work harder.’ I have a willingness now to work hard. You have to believe in yourself. That’s what’s most important. I’ve never doubted myself.”

“Jim is optimistic and stubborn. He has an incredible work ethic,” Connie said.

“He’s shown amazing determination. I’m completely overwhelmed with how he has turned around,” Honigman added.

The next step

In conversation, Cohen sprinkles references to “grit,” a combination of perseverance and practice much discussed in psychological and other professional circles today. Niehaus speaks of that quality in Cohen without using the word. Neurological rehabilitation depends on establishing new pathways to get information out of the brain, he said. Success depends on the patient’s willingness to put in the reps to blaze these new trails.

“They have to do the minute tasks over and over to get that pathway working, affirm it and progress to the next level,” he said.

The next level for Cohen will be June 25, when his daughter gets married. In September, he could offer only that affirmative blink. Now he stands from his wheelchair, showing he is ready to take the next step in a journey he has a hand in charting.

“I’m going to walk down that aisle,” Cohen said. “But I’m going to need to practice walking and crying.”