Student Voice

Mental Health Care Too Often Put on Hold

By Jamie Gilroy

(December 2017) Imagine the frustration of trying to reach a counselor and instead of hearing “we’re sorry, the number you have dialed is no longer in service.”

(December 2017) Imagine the frustration of trying to reach a counselor and instead of hearing “we’re sorry, the number you have dialed is no longer in service.”

Then imagine hearing it again for the second provider you try.

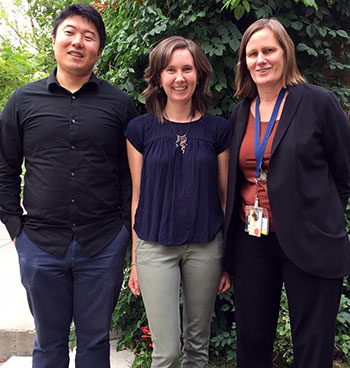

In our personal lives and in our work with preceptors, my fellow medical students, MariaElena Williams, and Tae Chang, and I had witnessed people struggling with access to behavioral health services.

Our mentor, Deb Seymour, PsyD, a primary care psychologist and associate professor of family medicine, who faces these challenges day in and day out, is aware of the significance of this problem and wanted a way to quantify it.

Together, with these observations so vivid in our lives, we developed our Mentored Scholarly Activity (MSA) project, a requirement of our CU School of Medicine education.

The manuscript that resulted from our study was published last summer in Annals of Family Medicine. In short, we found that even for people who are well insured, finding a mental health provider is difficult and time-consuming.

Wrong number

The summer after our first year of medical school, we three medical students collectively placed nearly 2,000 calls to psychiatrists, psychologists, licensed clinical social workers and licensed professional counselors in the Denver area.

During these calls, each of us

Those calls offered a glimpse into the uphill battle a patient faces when referred to therapy.

To start, the list of preferred providers for a specific insurance plan often provided incorrect or out-of-date information. Many phone numbers listed – we found 13 percent of them – were incorrect.

As of 2016, one year after we completed our data collection, federal guidelines require monthly directory updates. We hope that better oversight will decrease the unacceptably high number of inaccurate entries.

Other barriers

Beyond inaccurate phone numbers, we encountered providers who were no longer on the insurance company’s panel of approved providers, who worked only with select patient populations (e.g. those with eating disorders), and who simply had schedules too full to take new appointments.

The net result? Fewer than half of our calls resulted in an appointment. Psychiatry openings were particularly difficult to schedule. Based on our data, a patient needs to call seven to 10 psychiatrists to find an open appointment.

Most people with depression strain to complete the usual activities of daily life. Initiating new behavior is grueling for them. Is it really reasonable to expect those struggling with depression to complete the laborious process of accessing an online directory, calling multiple providers, waiting for return calls, and traveling – potentially great distances – to an appointment?

Insurance Does Not Guarantee Access

While Colorado’s uninsured rate fell from 14.3 percent in 2013 to 6.7 percent in 2015, our data indicates having health insurance does not guarantee access to behavioral health care. Surprised? We weren’t.

The Affordable Care Act includes mental health services as an essential health benefit for which insurance companies must provide “a network that is sufficient in numbers and types of providers…to assure that all services will be accessible without unreasonable delay.” But what is sufficient? It’s not defined. Several states have enacted additional legislation to clarify this requirement, but Colorado is not among them.

Our research focused on behavioral health care in metro Denver, but limitations in access are pervasive across regions and specialties. While conducting our research, we noted similar findings have demonstrated for psychiatric care in Maryland and New Jersey and for primary care in California.

While the future of health care reform still remains unclear, we feel strongly that network inadequacy must be addressed to ensure our patients can obtain the services they need.

Jamie Gilroy and Tae Chang are members of the medical school class of 2018. MariaElena Williams, MD, graduated in May. This project was their Mentored Scholarly Activity, a four-year requirement for all medical students.