Working Together Means Embracing the Jazz Ethos

Michael Harris-Love Mar 19, 2024

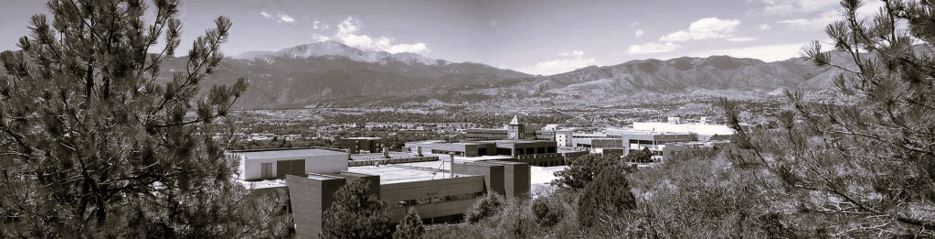

Starting a new thing is difficult. A new endeavor is exciting for the same reason that it invites danger – what lies around the corner may be either affirming or soul crushing. Such is life. Our program is in the process of building something new with university collaborators who are nearly 75 miles away. A daunting challenge when you consider it’s hard to convey a clear message to someone who works just down the hall merely minutes from your desk. Working on a shared goal while managing the unexpected is not unique to academia. There is a certain rhythm to a collective effort that rests upon individual voices within a group. As a professor and a long-time jazz listener, it’s fascinating to observe the similarities in group dynamics and shared leadership among jazz musicians and faculty members.

Efforts to codify shared academic governance is an ongoing process that includes attempts by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) in the early 1920s. The 1920s also proved to be a formative period for jazz and the players who would set the course for its continued development. Famed musician and educator, Wynton Marsalis, has referred to jazz as the quintessential expression of American culture and the most democratic guise of the arts. Marsalis gives credit to Louis Armstrong for crafting the template for the modern jazz soloist. Early jazz soloists such as Armstrong and others stretched the limits of the current sound thus finding ways to assert the voice of the individual while honoring the larger intent of the group. This progression of the music led to the democratic forms of managing the improvisational voice as demonstrated by leading lights such as Lester Young and Charlie Parker. This delicate dance does not come without effort. Child psychologists and…well, most parents, have observed the phenomenon of dueling monologues that often take place between two young children chatting on the playground. Musical dialogues (and faculty meetings) can also devolve into dueling monologues when left unchecked. But at its best, the interplay among soloists within a jazz ensemble requires making space for the other, respecting individuality, and reconciling differing approaches to rhythm or melody within the framework of a song. All lessons that well serve members of the professoriate. Marsalis calls this process “…having a dialogue with integrity.”

Marsalis also describes jazz as “the music of conversation” and a dialogue that is rife with the freedom of expression. Like other music genres, the freedom of expression is not absolute. (Even the subgenre of avant-garde jazz depends on the listener understanding the fundamental rules that are being intentionally broken.) Musical freedom exists within a structure that gives a genre its shape and depth. Ideas rise and fall based on the movement of the group. There is equality of opportunity, but not necessarily equality of results. When an idea fails to take hold or runs its course, the soloist must fall in line with the rhythm section and resolve the musical tension in service of the song. A remarkable thing about jazz is how groups noted for having strong leaders still have aural fingerprints that belong to a cast of players. Consider how John Coltrane’s Classic Quartet is grounded in the preternatural rhythmic stylings of their drummer, Elvin Jones. Likewise, it is a sheer impossibility to imagine the Bill Evans Trio without the nimble bass lines of Scott LaFaro. This is not to say that leadership doesn’t matter or that it should be subsumed by the collective. Indeed, the leadership of Miles Davis mattered in the rise of modal and fusion permutations of jazz. Likewise, the leadership of Ernest Boyer mattered in guiding the State University of New York system and promoting a more inclusive model of scholarship. Academic leader and scholar, Gary Olson, has correctly noted that “true shared governance attempts to balance maximum participation in decision making with clear accountability.” Directors, chairs, deans, and presidents cannot lead by fiat, and faculty committees, task forces, and boards cannot absolve the responsibility of appointed academic leaders. Rather, we continue to strive for a balance where faculty are active participants in governance and academic leaders assume ownership of the path taken.

Drummer extraordinaire, Art Blakey, is a somewhat unusual musical leader given the traditional supporting role of the rhythm section. However, he serves as an exemplary model of leadership in many respects for both the musician and the academic. Blakey’s group, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, had its early roots in the late 40s as an ensemble co-led with pianist, Horace Silver. Following the departure of Silver and other band mates, the group was sustained by a rotating cast of players anchored by Blakey’s presence at the drum kit. By the late 50s, the group had evolved into something akin to the most well-known “jazz residency” for up-and-coming players. While Blakey’s stylistic sensibilities were informed by the jazz’s hard bop period, he was known for prodding and guiding musicians though his playing – varying his approach to fills and comping based the perceived needs of the soloist. Blakey’s name is now synonymous with “longevity” within the jazz world. Band alumni ranging from Wayne Shorter and Lee Morgan, to Branford and Wynton Marsalis, graduated from the Jazz Messengers residency over the 35-year history of the group. Throughout his storied career, Blakey welcomed the contributions of others while also navigating tumultuous periods of change and maintaining accountability for the direction of the group.

The democratic ideals of jazz…its dependence on open dialogue and the precarious balance between freedom and structure, all serve as vivid reminders of the dynamic nature of shared leadership. By embracing this vision, we accept the uncertainty that lies just beyond the corner and the promise of building something even greater than we imagined.

Notes:

Kane A. A Great Day in Harlem. Esquire. January 1, 1959. New York City. pp. 98–99

Olson GA. Exactly What Is 'Shared Governance'? The Chronicle of Higher Education. July 23, 2009.

https://www.chronicle.com/article/Exactly-What-Is-Shared/47065 Accessed on December 29, 2019.

Sherman T. The Music of Democracy. UTNE Reader 74;March-April 1996: 29-36. Reprinted from American Heritage. October 1995.

Statement on the Government of Colleges and Universities, American Association of University Professors. https://www.aaup.org/report/statement-government-colleges-and-universities Accessed on December 29, 2019.