Shared Content Block:

Styles for CDB Faculty Pages

Michael McMurray, Ph.D.

Professor

| [email protected] | |

| 303-724-6569 | |

| Ph.D., University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 2004 |

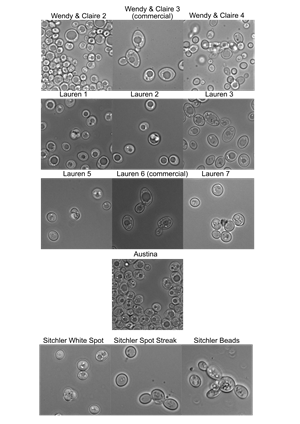

Figure 1. The structure of a homodimer of the human septin SEPT2 bound to the nonhydrolyzable GTP analog GppNHp (PDB 3FTQ) with the residues corresponding to those we found in temperature-sensitive yeast rendered as spheres. GppNHp is shown in orange. From Weems, et al GENETICS 2013.

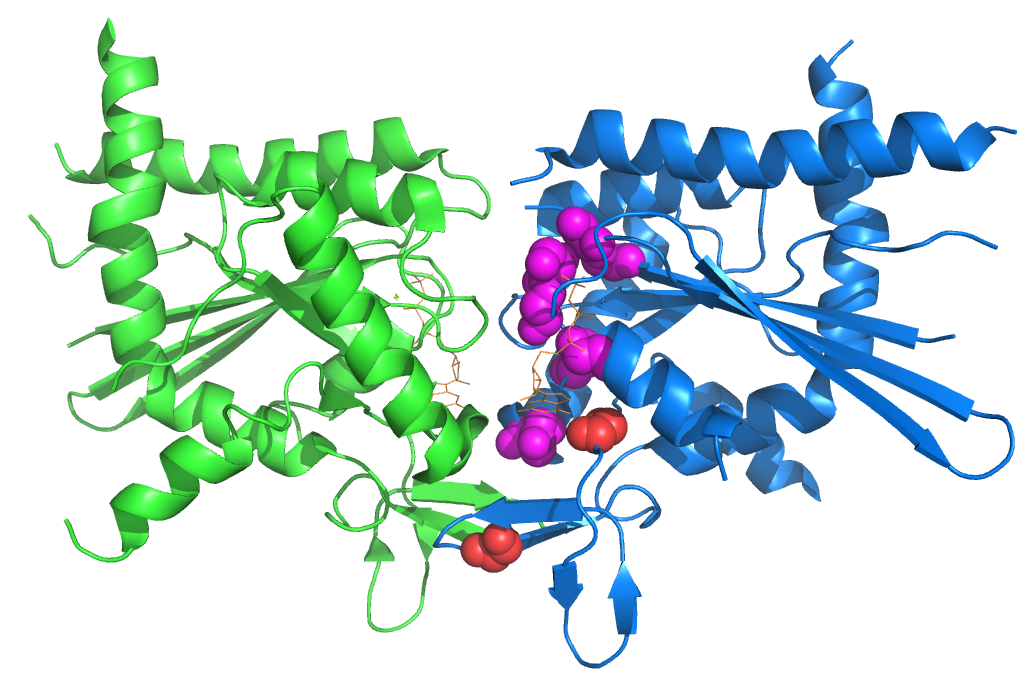

Figure 2. Model for chaperone-mediated quality control of higher-order septin assembly. Nascent septin polypeptides emerging from the ribosome encounter a number of cytosolic chaperones during subsequent de novo folding. Wild-type septins efficiently adopt quasi-native conformations, thereby burying hydrophobic residues and escaping chaperone-mediated sequestration. Heterodimerization with other septins—the first oligomerization step toward septin filament assembly—occurs concomitant with exit from the chamber of the cytosolic chaperonin CCT (also called TRiC). Mutant septins that inefficiently fold the G heterodimerization interface are slower to achieve a conformation allowing chaperone release. Interactions with the prefoldin complex (PFD), the Hsp40 chaperone Ydj1, and the disaggregase Hsp104 are particularly prolonged, leading to a delay in availability of the mutant septin for hetero-oligomerization. From Johnson, et al Mol Biol Cell 2015.

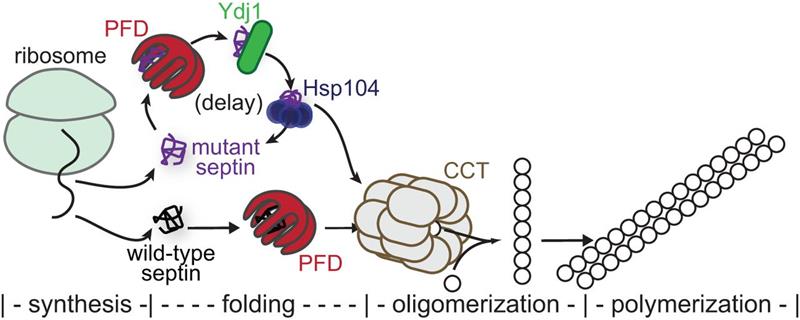

Figure 3. Model for the step-wise assembly of yeast septin hetero-octamers. From Weems & McMurray, eLife 2017.

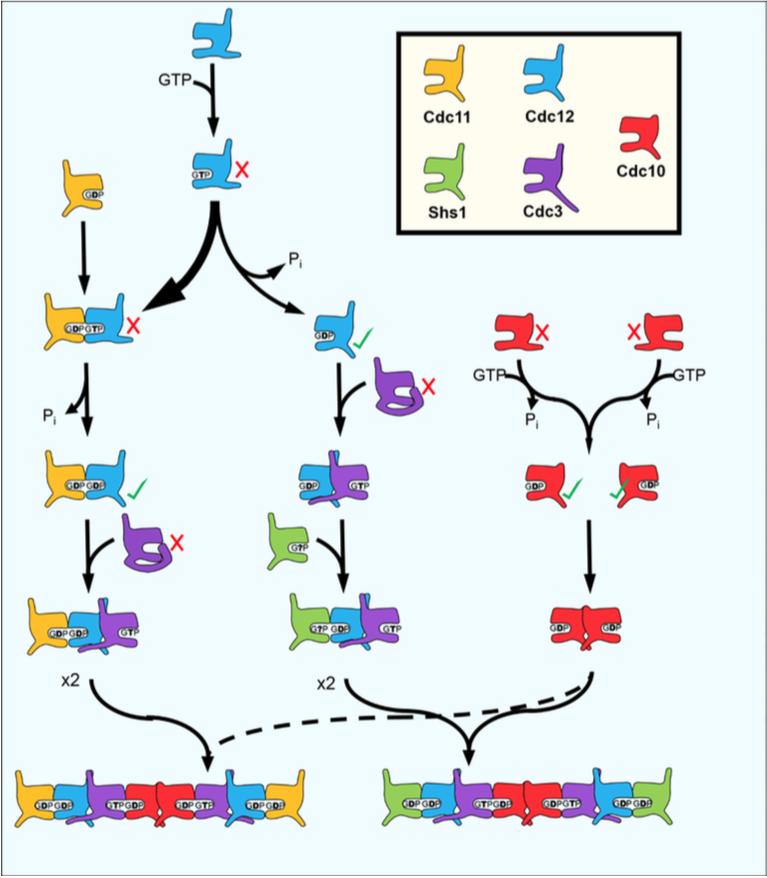

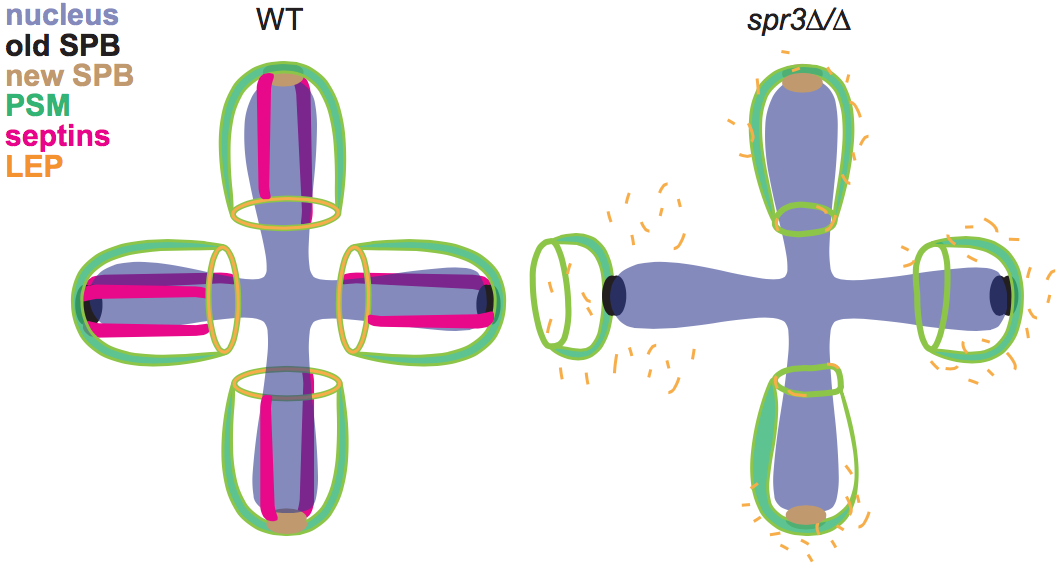

Figure 4. Model for the defects in prospore membrane (PSM) biogenesis in septin-mutant yeast cells. SPB, spindle pole body; LEP, leading edge protein. From Heasley & McMurray, Molecular Biology of the Cell 2016.

Our research focuses on identifying molecular mechanisms underlying the assembly of macromolecular complexes, with a focus on multisubunit complexes formed by septin proteins. All cellular processes require the function of multisubunit complexes, and while much attention has been given to solving the final structures of such assemblies, comparatively little is known about how individual subunits adopt oligomerization-competent conformations and find their partner subunits in the crowded, dynamic cellular milieu.

In our research we mostly use the premiere eukaryotic experimental system for genetic analysis, the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Studies of septin protein function in yeast gametogenesis led us to begin to explore some fundamental unanswered questions about yeast gametes.

Below is a summary of recent research from our group in these two areas.

“What does GTP do for septins?” This question was posed in 2002 in Current Biology by Tim Mitchison and Chris Field, reflecting the awareness that septins clearly evolved from an ancestral GTPase and most septins bind GTP, but some do not hydrolyze it and nucleotide exchange is very slow. How GTP binding and/or hydrolysis relates to septin structure or function was unknown. Over the last 13 years, my lab answered this question. Using simple genetic approaches, we demonstrated that GTP binding is dispensable for septin function and merely guides de novo folding towards an oligomerization-competent state (Weems et al., 2014). We next developed a new method for determining the temporal order of protein-protein interactions in living cells, and with it revealed the step-wise pathway for septin hetero-octamer assembly in yeast (Weems and McMurray, 2017). In doing so, we found that slow GTP hydrolysis by one septin enforces order of assembly and mediates the choice of incorporation of the two alternative “competing” subunits at one subunit position in septin octamers (Weems and McMurray, 2017). During yeast evolution loss of GTP hydrolysis by another septin eliminated an alternate assembly pathway that humans and other fungi use to make hexamers in addition to octamers (Johnson et al., 2020). Slow GTP hydrolysis controls septin assembly pathways by creating a transient GTP-bound septin that has a distinct affinity for partner septins compared to the GDP-bound form (Weems and McMurray, 2017; Johnson et al., 2020). Crucially, this feature allows septin assembly pathways to respond to the GTP:GDP ratio in the cytoplasm (Weems and McMurray, 2017), providing a way for cells to tailor the composition of their septin complexes to current cellular demands. Human cells almost certainly use this mechanism to choose what kinds of complexes they assemble from the 13 distinct human septin genes. Finally, we revealed additional examples throughout phylogeny of how loss of GTP hydrolysis or GTP/GDP binding altogether drove changes in septin-septin assembly interfaces that likely reflect adaptation to metabolic changes resulting in varying nucleotide levels (Hussain et al., 2023).

Requirements for de novo septin complex assembly. Monomers of actin and tubulin require folding assistance from cytosolic chaperones. We first discovered that cytosolic chaperones mediate a kind of “quality control” over septin assembly, imposing a kinetic disadvantage on slowly-folding mutant septins that favors incorporation of wild-type septins into complexes (Johnson et al., 2015). These findings demonstrated a new role for general cytosolic chaperones in the expression of subtly misfolded mutant alleles, representing a new paradigm in cytosolic cellular proteostasis (Schaefer et al., 2016). We next used direct in vivo approaches to identify septin-chaperone interactions (Denney et al., 2021) and a combination of in vivo crosslinking and in vitro reconstitution to show that specific cytosolic chaperones engage nascent septin polypeptides to promote efficient septin complex assembly (Hassell et al., 2022). We also discovered that simultaneous co-overexpression of two yeast septins (one fused to a small tag) is sufficient to drive an unprecedented phenotype: filaments composed of only those two septins localized all over the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (Benson and McMurray, 2023). These findings represent key advances in our understanding of the molecular requirements for septin-septin interactions, complex assembly, and membrane association.

Chemical rescue of mutant protein function in living cells. During our septin studies we serendipitously discovered that the small molecule guanidine hydrochloride is able to restore the folding and/or function of certain missense mutants in vivo (Johnson et al., 2020; Hassell et al., 2021). In at least some cases (including a mutant allele of actin that is linked to cardiac disease, and a mutant allele of ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) linked to OTC deficiency) this rescue involves replacement by the guanidinium ion of an arginine side chain. Such replacement had been shown for some proteins in vitro but had never been demonstrated in living cells. We went on to explore chemical rescue by other naturally occurring small molecules, and found hundreds of examples of mutant rescue in living cells by molecules like DMSO and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) (Hassell et al., 2021). TMAO, found naturally in marine organisms that experience high levels of urea or hydrostatic pressure, rescued ~20% of the mutants we tested (Hassell et al., 2021). These findings point to influences of intracellular small molecules on protein evolution, as well as possible therapeutic interventions for genetic diseases.

Establishment of sexual identity and cell polarity during budding yeast gametogenesis. Diploid yeast cells produce haploid gametes by coupling meiosis to sporulation, a specialized form of cytokinesis. We studied septin assembly and function in sporulation (Heasley and McMurray, 2016; Garcia et al., 2016) and found that septins mark a cortical site in spores that directs polarized outgrowth away from contacts with sister spores (Heasley et al., 2021). We also explored a surprisingly open question: Since the four gametes produced by a single diploid cell are of two different sexual identities, and mating/fertilization requires mutually exclusive gene expression programs, how is it that these expression programs begin early in gametogenesis, before the gametes are fully formed and isolated from each other? We found evidence of a variety of post-transcriptional mechanisms that may inhibit translation of sex-specific mRNAs made “too early”, including antisense transcription and extended 5’ UTRs with upstream open reading frames (uORFs) (Yeager et al., 2021).

.

View Dr. McMurray's Latest Publications in PubMed

Unlocking Clues to Potential Therapies for Genetic Diseases. Michael McMurray. 2025

Roles for the canonical polarity machinery in the de novo establishment of polarity in budding yeast spores. Benjamin Cooperman, Michael McMurray. 2025

Stepwise order in protein complex assembly: approaches and emerging themes. Michael T. Brown, Michael McMurray. 2025

Wild yeast isolation by middle-school students reveals features of populations residing on North American oaks. Randi Yeager, Lydia R Heasley, Nolan Baker, Vatsal Shrivastava, Julie Woodman, Michael A McMurray. 2025

Evolutionary degeneration of septins into pseudoGTPases: impacts on a hetero-oligomeric assembly interface. Alya Hussain, Vu T. Nguyen, Philip Reigan, Michael McMurray. 2023

Simultaneous co-overexpression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae septins Cdc3 and Cdc10 drives pervasive, phospholipid-, and tag-dependent plasma membrane localization. Aleyna Benson, Michael McMurray. 2023

Chaperone requirements for de novo folding of Saccharomyces cerevisiae septins. Daniel Hassell, Ashley Denney, Emily Singer, Aleyna Benson, Andrew Roth, Julia Ceglowski, Marc Steingesser, and Michael McMurray. 2022

Proteasome activity modulates amyloid toxicity. Galvin, John; Curran, Elizabeth; Arteaga, Francisco; Goossens, Alicia; Aubuchon-Endsley, Nicki; McMurray, Michael; Moore, Jeffrey; Hansen, Kirk; Chial, Heidi; Potter, Huntington; Brodsky, Jeffrey; Coughlan, Christina. 2022

Meeting report - the ever-fascinating world of septins. Anita Ballet, Michael A. McMurray, Patrick W.

Oakes. 2021

Post-Transcriptional Control of Mating-Type Gene Expression during Gametogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Randi Yeager, G. Guy Bushkin, Emily Singer, Rui Fu, Benjamin Cooperman, and Michael McMurray. 2021

Chemical rescue of mutant proteins in living Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells by naturally occurring small molecules. Daniel S Hassell, Marc G Steingesser, Ashley S Denney, Courtney R Johnson, Michael A McMurray. 2021

Discussed in: Naturally occurring small molecules correct mutant proteins in living cells

Selective functional inhibition of a tumor-derived p53 mutant by cytosolic chaperones identified using split-YFP in budding yeast. Ashley S Denney, Andrew D Weems, Michael A McMurray. 2021

Saccharomyces spores are born prepolarized to outgrow away from spore–spore connections and penetrate the ascus wall. Lydia R. Heasley, Emily Singer, Benjamin J. Cooperman, Michael A. McMurray. 2020

Masters of asymmetry - lessons and perspectives from 50 years of septins. Spiliotis ET and McMurray MA. 2020

Guanidine hydrochloride reactivates an ancient septin hetero-oligomer assembly pathway in budding yeast. Johnson CR, Steingesser MG, Weems AD, Khan A, Gladfelter A, Bertin A, McMurray MA. 2020

Turning it inside out: The organization of human septin heterooligomers. McMurray MA and Thorner JT. 2019

The long and short of membrane curvature sensing by septins. McMurray MA. 2019

Septins are involved at the early stages of macroautophagy in S. cerevisiae. Barve G, Sridhar S, Aher A, Sahani MH, Chinchwadkar S, Singh S, K N L, McMurray MA, Manjithaya R. 2018

The step-wise pathway of septin hetero-octamer assembly in budding yeast. Weems A, McMurray M. 2017

Coupling de novo protein folding with subunit exchange into pre-formed oligomeric protein complexes: the 'heritable template' hypothesis. McMurray MA. 2016

Small molecule perturbations of septins. Heasley LR, McMurray MA. 2016

Assays for genetic dissection of septin filament assembly in yeast, from de novo folding through polymerization. McMurray MA. 2016

Kinetic partitioning during de novo septin filament assembly creates a critical G1 "window of opportunity" for mutant septin function. Schaefer RM, Heasley LR, Odde DJ, McMurray MA. 2016

Assembly, molecular organization, and membrane-binding properties of development-specific septins. Garcia G 3rd, Finnigan GC, Heasley LR, Sterling SM, Aggarwal A, Pearson CG, Nogales E, McMurray MA, Thorner J. 2016

Roles of septins in prospore membrane morphogenesis and spore wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Heasley LR, McMurray MA. 2016

Cytosolic chaperones mediate quality control of higher-order septin assembly in budding yeast. Johnson CR, Weems AD, Brewer JM, Thorner J, McMurray MA. 2015

Off-target effects of the septin drug forchlorfenuron on nonplant eukaryotes. Heasley LR, Garcia G 3rd, McMurray MA. 2014

Lean forward: Genetic analysis of temperature-sensitive mutants unfolds the secrets of oligomeric protein complex assembly. McMurray MA. 2014

Higher-order septin assembly is driven by GTP-promoted conformational changes: evidence from unbiased mutational analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Weems AD, Johnson CR, Argueso JL, McMurray MA. 2014

Native cysteine residues are dispensable for the structure and function of all five yeast mitotic septins. de Val N, McMurray MA, Lam LH, Hsiung CC, Bertin A, Nogales E, Thorner J. 2013

Three-dimensional ultrastructure of the septin filament network in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bertin A, McMurray MA, Thorner J, Peters P, Zehr E, McDonald KL, Thai L, Pierson J, Nogales E. 2012

Subunit-dependent modulation of septin assembly: Budding yeast septin Shs1 promotes ring and gauze formation. Garcia G III, Bertin A, Li Z, Song Y, McMurray MA, Thorner J, Nogales E. 2011

Genetic interactions with mutations affecting septin assembly reveal ESCRT functions in budding yeast cytokinesis. McMurray MA, Stefan CJ, Wemmer M, Odorizzi G, Emr SD, Thorner J. 2011

Septin filament formation is essential in budding yeast. McMurray MA, Bertin A, Garcia III G, Lam L, Nogales EE and Thorner J. 2011

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate promotes budding yeast septin filament assembly and organization. Bertin A, McMurray MA, Thai L, Garcia III G, Votin V, Grob P, Allyn T, Thorner J and Nogales EE. 2010

Pheromone-induced anisotropy in yeast plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate distribution is required for MAPK signaling. Garrenton LS, Stefan C, McMurray MA, Emr SD and Thorner J. 2010

Septins: molecular partitioning and the generation of cellular asymmetry. McMurray MA and Thorner J. 2009

Reuse, replace, recycle: Specificity in subunit inheritance and assembly of higher-order septin structures during mitotic and meiotic division in budding yeast. McMurray MA and Thorner J. 2009

Biochemical properties and supramolecular architecture of septin hetero-oligomers and septin filaments. McMurray MA and Thorner J. 2008

Septin stability and recycling during dynamic structural transitions in cell division and development. McMurray MA Thorner J. 2008

Saccharomyces cerevisiae septins: supramolecular organization of heterooligomers and the mechanism of filament assembly. Bertin A*, McMurray MA*, Grob P*, Park SS, Garcia G 3rd, Patanwala I, Ng HL, Alber T, Thorner J, Nogales E. 2008

Current Lab Members

Michael Brown

PhD student (Molecular Biology Program)

Marc Steingesser

Lab Manager (and lab dad)

Former Lab Members

Alya Hussain

Postdoctoral Research Associate at Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center

Ben Cooperman, PhD

Instructor at the University of California San Diego Division of Extended Studies

Randi Yeager, PhD

Sales Specialist at Oxford Nanopore

Aleyna Benson

Research Associate II at KBI Biopharma

Daniel Hassell

PhD student in the Molecular, Cell, and Development program, University of Colorado Boulder

Ashley Denney, MD, PhD

Resident Physician, University of Colorado

Andrew Roth, PhD

Research Writer and Regulatory Specialist in the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, University of Colorado AMC

J.P. Darling-Munson

AAV Research Associate, Rocket Pharmaceuticals

Emily Singer

PhD student in the Molecular Biology program, Princeton University

Lydia Heasley, PhD

Assistant Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Colorado AMC

Andrew Weems, PhD

Instructor with the Lyda Hill Department of Bioinformatics and Post-Doc in the Danuser Lab, UT Southwestern Medical Center

Courtney Johnson, DDS

Practicing Dentist in Charlotte, NC

Rachel Schaefer, BS

Antimicrobial Stewardship Epidemiologist, Colorado Dept. Public Health and Environment

Christina Coughlan, PhD, FCP, SI, EMT

Research instructor in Department of Neurology, University of Colorado AMC

The Wild Yeast Outreach Program

Funded by the National Science Foundation through award 1928900

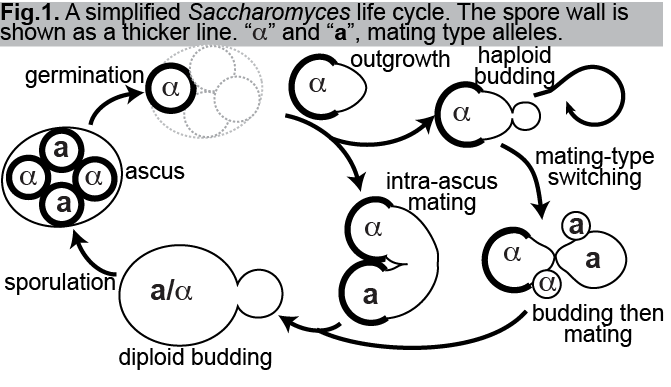

After >100 years of study, the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the best understood eukaryotic cell. A key feature that makes S. cerevisiae such a powerful tool for genetical manipulation is the efficient alternation of haploid and diploid phases (Fig. 1). Upon nutrient deprivation, most diploid S. cerevisiae strains undergo meiosis and sporulation, typically producing four haploid spores within each sporulating cell. Each spore is encased in a specialized wall that confers resistance to a variety of environmental stressors. As the two mating types reflect alternative alleles at a single locus, each meiosis produces two pairs of spores of opposite mating types, "a" and "alpha". In the lab we prevent mating between spores by physically separating them before exposing them to nutrients, which allows them to grow out from the spore wall (“germinate”) and proliferate indefinitely via budding (Fig.1). Whereas a haploid spore from most natural isolates is able to switch mating types and, via subsequent mating with one of its offspring, return to the diploid state (Fig. 1), labs use haploid strains incapable of switching. Instead, diploids are made at will by mating between haploids placed in close proximity. The ability to manipulate genes and study effects in the haploid phase and then to combine different alleles via mating/recombination/sporulation is the foundation of yeast genetics. Exploiting this life cycle in the lab context has extended our understanding of the cellular and molecular biology of S. cerevisiae to a level of detail unparalleled by any other eukaryote.

Despite (or, more likely, because of) our focus on S. cerevisiae as a model for human biology, the yeast field tends to ignore the aspects of yeast biology that lack direct counterparts in human cells. Only recently have we begun to realize that in order to fully understand yeast biology, we must consider how this organism lives outside the lab.

Since in the lab germination is almost always done with isolated spores, most yeast researchers assume that if the spores are kept in contact, they will always mate. Not true! Spores frequently bud even when they are right next to a potential mating partner. Why? How does a spore decide whether to mate, or to bud?

We want to understand the circumstances in which a germinating spore buds vs mates. The research goal of this outreach program is to test the hypothesis that the tendency of a natural Saccharomyces isolate to bud vs mate upon germination can be predicted by assessing HO gene function. The HO gene is essential for mating-type switching and is only expressed in haploid cells that have budded at least once (Fig. 1). HO is thought to have evolved to allow a return to diploidy in cases where spores are dispersed. This trait is called homothallism; the failure to do so is heterothallism. If a strain never sporulates or always mates upon germination (no “lonely spores”), HO is never expressed, and mutations can, in principle, accumulate.

We hypothesize that natural Saccharomyces isolates carrying mutant HO alleles but capable of sporulation will be biased towards intra-ascus mating upon germination. To test this hypothesis, we isolate Saccharomyces species from the wild, sequence the HO locus in each, and assess sporulation ability and bud-vs-mate decision upon germination.

To engage the public in scientific research and enrich public school education in a way that also advances the research goals of our project, we involve members of the general public in the isolation and identification of yeast strains from the bark of oak trees or sourdough starters, and the identification of mutations in HO causing defects in mating-type switching. Here we provide a collection of resources that we have developed, which we hope will be of value to other groups undertaking similar outreach efforts.

2019 Middle School Outreach

In October 2019 for the first time we incorporated undergraduate students from Colorado Christian University in the outreach activity with Morey Middle School 6th-grade students. CCU students (Biology and Elementary Education majors) were exposed directly to what it is like to teach Biology to middle-school students. CCU students also received the oak bark samples and successfully isolated yeast from them, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which was confirmed by PCR of ITS2 DNA and sequencing. At the time of the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown, CCU students were attempting to amplify the HO gene for sequencing. CCU students thus also received direct, hand-on training in biological research.

| Description | File/link |

|---|---|

| Intro lecture | Wild Yeast Project.pdf |

| DNA barcoding lecture | Species ID by DNA sequencing.pdf |

| Yeast ID by microscopy quiz | Wild Yeast Microscopy of Bark Cultures |

| Map of oak yeast identified in Cheesman Park | FinalCheesmanYeastMap.pdf |

2020 Wild Sourdough Yeast Outreach

The COIVD-19 pandemic closed Morey Middle School and the Aurora School of Science and Technology, preventing the planned Spring 2020 outreach activities. PI Michael McMurray regularly attends an entirely volunteer-led annual retreat for families with profoundly gifted children (PG Retreat, or PGR; www.pgretreat.org). The in-person event scheduled for the end of June 2020 was canceled, and Michael volunteered to help design and execute a set of virtual, online activities in its place. Michael realized that with the explosion of the use and creation of sourdough starters that accompanied the pandemic-associated shelter-in-place orders, a large number of PGR registrants would likely be interested in a version of the Wild Yeast Isolation outreach activity modified to use sourdough starters as a source of yeast.

Michael spoke with scientists from North Carolina State University’s “Public Science Lab” (http://robdunnlab.com), which has been organizing a “Science of Sourdough” citizen science project (http://robdunnlab.com/projects/wildsourdough) that asks citizens from all over the world to measure properties of sourdough starters. Michael then recruited >20 PGR registrants to participate in a 7-week program that involved many of the same activities as used for middle-school students, but also included isolation of the yeast from the starters using homemade medium, and mailing the yeast to the McMurray lab for analysis. We were successful!

| Description | File/link |

|---|---|

| Intro lecture | Wild Sourdough Yeast |

| DNA barcoding lecture | Yeast 23 & Me |

| Home microbiology basics lecture | Isolating Microbes from Starters |

Photos of plates and yeast cells from starters