Investigate the Problem

The investigate step is the foundation of the IHQSE Model for Change. It creates clarity as to the exact problem, highlights the organizational impact of the problem, and establishes the desired outcomes for your work. This foundation sets the model in motion ensuring downstream success.

Your QI efforts can and should be built on the foundation of work done previously. If someone, somewhere has figured how to do something in this area, you should know that and incorporate it as appropriate.

A literature search allows you to compare your problem and potential interventions with what has been published on the topic.

The search may occur early in the investigate phase to understand what is known about the problem and later in the hone phase to understand what is known about potential interventions.

Early searches, typically in the investigate phase, are key for benchmarking purposes within your problem statement and to creating a sense of urgency for change.

This process gives you a sense of the current state at other healthcare systems, or at a national level allowing you to make statements such as ‘over 50% of people with diabetes in this country are not at goal glycemic control,’ followed by your local baseline data: ‘and in our clinic, 60% are not achieving goal A1c.”

Later searches, usually in the Hone phase after you have an intervention in mind, should use the PICO system to methodically understand what has been published. It utilizes keywords that are put into a searchable database like PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Google Scholar or ScienceDirect.

The four core search elements are the Population/Patients, Interventions, Comparison group, and Outcomes.

- Step 1: Identify the patients or population you are interested in. You may require more than one group of patients, e.g., ‘mechanical ventilation,’ ‘mechanical ventilator,’ and ‘artificial respiration’ to capture all of the ways this information may have been published.

- Step 2: Delineate the intervention you are considering. E.g., ‘weaning’ and ‘protocol.’

- Step 3: Identify a comparison group. E.g., ‘non-protocol’ patients.

- Step 4: Clarify the outcome you are looking for. E.g., ‘ventilator days’ or ‘mortality.

Your problem statement captures the issue you are planning to tackle and proves to your audience that you have a problem, using data. This should be a simple sentence that captures WHAT your problem is, followed by data to prove it. An effective problem statement should address the following questions:

- Step 1: How do you know you have a problem?

- Step 2: Who is affected by the issue?

- Step 3: By how much are they effected?

- Step 4: Which metrics will you use to prove you the above?

Examples:

- Over-sedation of patients in the ICU increases mortality by 25%, leading to 30 additional deaths per year.

- Inappropriate use of physical therapy consultation wastes 10,000 hours of therapist time each year.

- The pulmonary embolism pathway is used 50% of the time, and when not used, doubles PE mortality.

To include data to support your problem statement, you should engage in a literature search, determine key metrics, and acquire baseline data. Together, they help support that you have a problem locally, and that it is important at a broader level.

Data to Understand Your Problem Worksheet

As you are investigating your problem, you want to ensure you have data that documents the problem while allowing you to track over time to show your improvement. There are 4 types of metrics that we use in process improvement:

- Step 1: Identify Outcome Metrics – This is the metric that captures the ultimate outcome of your project. It is usually something that directly impacts patients, such as experience, mortality, or safety events. As a result, it can take a long time (typically months to years) to see a change in this type of metric. While you should be tracking outcome metrics, you’ll also want to track other metrics that give you a more rapid sense of if the intervention is working.

- Examples: Number of DVTs, deaths from sepsis, strokes in patients with hyperlipidemia, admissions to the hospital for asthma patients.

- Step 2: Identify Process Metrics – This metric captures a step that we know, or think, leads to the desired outcome, but is usually easier to measure in real time, or at a more rapid frequency. This allows you to know if your intervention is working more quickly than an outcome metric. As a result, these commonly become part of the aim statement.

- Example: If we want to prevent DVTs in the hospital, the percentage of time we prescribe DVT prophylaxis is a process metric, because we KNOW that more DVT prophylaxis prevents DVTs. DVTs (outcome metric) take longer to measure because they are a rare event, but every day you can measure how many times DVT prophylaxis is prescribed.

- Step 3: Identify Structural Metrics – This metric captures structures that are needed to provide optimal care, such as number of beds or number of staff members. Not all projects have structural metrics. Like process metrics, these often make up the aim statement.

- Example: For the DVT problem – you need to ensure you have enough access to heparin (the medication used for DVT prophylaxis) and enough nursing time to administer the medication. These are structural metrics. Other structural metrics for different projects could include the presence of 24/7, in-house intensivists or a diabetic educator in clinic.

- Step 4: Identify Balancing Metrics – This metric captures the potential unintentional negative consequences of your project work.

- Example: If the goal is to increase DVT prophylaxis with blood thinner medications, ensure you are not causing a higher bleeding rate. The rate of bleeding is your balancing metric.

Each of these metrics will become part of your Data Acquisition plan.

Successful QI work is dependent on data. There are three major uses for data. First, to understand the scope of your problem. Second, to understand the cause of your problem. Three, to understand the impact of your intervention.

- Step 1: Find data to understand the scope of the problem.

- This is often, but not always an outcome metric such mortality in sepsis, Alc control in diabetes, or time to next visit in a clinic.

- Common sources of these data include the electronic health record, publicly reported measures, or data on a quality dashboard.

- Consider sources such as national benchmarking groups like Vizient, Premier, or Health Catalyst. CMS, state Medicaid and sometimes (but often harder to get) private insurers can be a source of data. Finally, national rankings such as US News and Healthgrades may offer insights.

- Many times, you’ll need to build and/or pull reports from your electronic health record. This may require a data person’s support but some of these data may be found through tools like Epic’s Slicer Dicer.

- Step 2: Find data to understand the cause of the problem

- These are nearly always process metrics and are crucial to understanding the cause of the outcome.

- For example, time to antibiotics, number of blood pressure readings per year, inhaler prescription fill rates are all process measures that may impact sepsis mortality, blood pressure control, and hospital admissions for asthma, respectively.

- These data are crucial because they often help to reveal the point where you’ll intervene.

- These data are infrequently publicly reported, found on a dashboard or readily available. They usually require a data pull from the electronic health record or chart review.

- Chart review is a way to get data quickly (although it can be time consuming) to understand your problem. Get just enough data to understand the problem, not a bit more. This may be as few as 10 charts, and almost never 200 charts. This is time consuming work, use chart review sparingly.

- You may also get these types of data from surveys, process mapping (especially if you are evaluating rates of fidelity with the process steps), affinity diagram, and your voice of the customer (likely more qualitative, though).

- Step 3: Find data to understand the impact of your interventions.

- These are usually process measures but may include the outcome measure as well (as a long-term measure).

- While chart review can be effective in step 2, you should try to avoid using it for step 3. Rather step 3 should include data that is compiled automatically, typically from the electronic health record.

- Work with your local data team to build reports to pull this data at relatively frequent intervals so that you can learn if the intervention is having an impact, share with your team to motivate continued change, and inform future interventions.

Stakeholder Analysis Worksheet

A stakeholder analysis is a process of understanding which people may influence your work or be impacted by it. It will ensure that you are engaging the correct people early (Investigate phase) as you understand your problem and later (eQuip phase) as you manage the change around your project.

- Step 1: Identify your stakeholders

- Make a list of all the groups and key individuals who may have a perspective on the problem you are tackling or are impacted by it. This can include patients and families, providers, staff, administrative team members, and the executive leadership.

- Step 2: Determine where your stakeholders are on the power:interest grid

- Power mapping—a good rule of thumb is that those in a ‘high power’ category are likely a named individual or roles (not a group of individuals). While physician groups may seem powerful/influential, their Chief or Quality Chair are the power people, not the group.

- Interest mapping—you may not know how interested in your efforts an individual may be until you pursue your Voice of the Customer so this mapping is subject to change. A major danger is to underestimate a high-power person’s interest such that you do not keep them adequately informed. High-power individuals may not recognize their interest until later. This results in them sliding into the high:high quadrant—you should adjust your engagement accordingly when this happens.

- Step 3: Determine degree of engagement

- High power/high interest: Manage Closely.

- These are key stakeholders. Generally, this group will be identifiable individuals, not necessarily large categories of people.

- As a rule of thumb, you should meet with these individuals on a regular cadence, likely monthly, and send email communication in between.

- Their feedback and perspective should be integrated into decision-making and they should be fairly intimately familiar with your work.

- These people should be looped in on issues BEFORE others hear about it. You do not want them to be surprised by information they haven’t heard from you first.

- Ideally your executive sponsors are in this category—to promote your work and to be invested enough to remove barriers, they need to know what’s happening. If there are important updates or issues they need to know before it goes public.

- High power/low interest: Keep Satisfied.

- They need regular updates—in particular, this group can be helpful in elevating your successes and potentially removing larger system barriers.

- Their feedback is also important but may not be required for all decision-making.

- As a rule of thumb, you should be meeting or emailing updates to this group on a roughly monthly basis.

- Low power/high interest: Keep informed.

- These are usually larger groups of individuals and often represent a customer base of sorts (E.g., the residents, the nurses on a unit, or the clinic providers).

- While their perspective is important to decision-making, they are usually not directly engaged in making decisions.

- As a rule of thumb, you should meet with this group in the beginning and then update biannually or with major updates.

- One caveat. Most often these are people you are eventually going to ask to adopt a behavioral change in the start phase of the IHQSE Model for Change. Once you go live with your intervention, this group needs a lot of communication about the change (the sense of urgency, logistics, etc.) and should be a focus of your celebration.

- Low power/low interest: Monitor.

- These individuals just need major project updates.

- As a rule of thumb, you may consider a quarterly (or biannual depending on pace of program) update.

- High power/high interest: Manage Closely.

Voice of the Customer Worksheet

The Voice of the Customer tool is a way for you to gain an understanding of your key stakeholders and their thoughts on your problem — including their relevant motivations, perspectives, and needs.

The goal of this process is to learn what is going well, what is not going well, and what are their ideas for improvement.

Even if you think you know a group's perspective, performing a VOC allows you to engage and communicate with them in a way that helps them to feel heard. And, most often, you will learn something you didn’t know! This process also plays a crucial role in identifying people interested in helping you, signaling that change is coming, and that you want their support.

- Step 1: Identify your stakeholders.

- This is the same as the first step of stakeholder mapping.

- Make a list of all the groups and key individuals who may have a perspective on the problem you are tackling or are impacted by it. This can include patients and families, providers, staff, administrative team members, and the executive leadership.

- Step 2: Create methods of engagement.

- Once you’ve decided what groups and individuals you want to learn from, you should choose an appropriate modality to engage with them – this can be informal conversations, individual interviews or focus groups, or surveys.

- Step 3: Feed the information back to them.

- This is technically not required for a VOC intervention but is an opportunity to engage them in the process such that they are more aware of the work, feel they have contributed to it, and feel heard. This will go a long way to helping gain their buy-in in the eQuip and start phases of the IHQSE Model for Change.

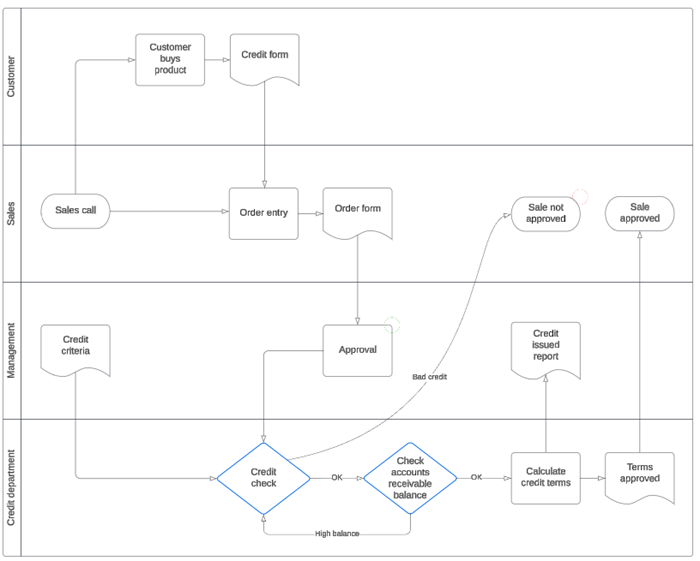

The goal of your Process Map is to make the process that you are trying to improve more visible to each team member and stakeholder. It allows you to see each step that may otherwise be invisible to you. This is a team activity given the siloed nature of our work, and is best done in person, with a whiteboard and sticky notes.

Recognize that process mapping is a technical tool to understand how work gets done. But the process of process mapping is an adaptive tool that creates engagement, inclusion and buy-in. It allows all team members to share their ideas, insight, and improvement ideas, and messages that you care about their feedback.

- Step 1: Identify the start and stop of the process.

- This allows the team to agree on the scope of the problem.

- For example: For a problem tackling a long length of stay in the hospital, what is the process start? Is it when the patient shows up at the emergency room? When the ER doctor decides to admit them? When the patient gets to their bed in the hospital? Or when the primary team places the first of orders? Each of these starts suggests a different scope of project work.

- Step 2: Determine the entity you are following.

- This may include a person, material, or information.

- For example: Some processes follow a person – such as a patient moving through a hospital admission. Others follow a material – consider a process looking at lost phlebotomy samples, that tracks where the blood samples travel in a hospital. Finally, others follow information – consider a patient calling a clinic with a question, and the process to understand who answers that question.

- Step 3: Add the discrete steps.

- For this step, you will need representation from many different viewpoints, as it is likely that you don’t fully see or understand other's role in a process.

- In general, process mapping should use a top-down approach. That is, start at a high-level with the essential steps that take you from beginning to end. As you begin to hone in on an area of potential interest then you should consider diving deeper into each step including who is doing what and how. As a rule of thumb, start very broad and add detail as necessary.

- Example: A Rapid Response Process Map should include which providers/staff are involved, how they are contacted, where they show up, and what their high-level responsibilities are. You do not need to get into details such as which room the code cart is stored in, who needs to get it, and who restocks it. However, if you later determine that this is a pain point you may indeed provide deeper detail on these steps.

- Step 4: Identify the steps that cause pain.

- These may include steps that yield waste, inefficiency, and frustration.

- These are steps that the team can agree are unnecessary (duplicative efforts), problematic (causes frustration), or highly variable (everyone does it a different way.)

- You will likely need to provide more depth of detail to these steps to best understand your areas of potential intervention.

- Step 5: Identify the steps that bring joy and connection!

- You want to try not to eliminate these steps! You may have to do so because the step is so inefficient but weigh the upsides of efficiency gains against the downsides of losing provider/staff satisfaction in their work with the change.

- For example, if spending the time counseling a patient on their care plan is highly valuable for the provider don't make a change that will eliminate this face-to-face interaction as it will be a dissatisfier.

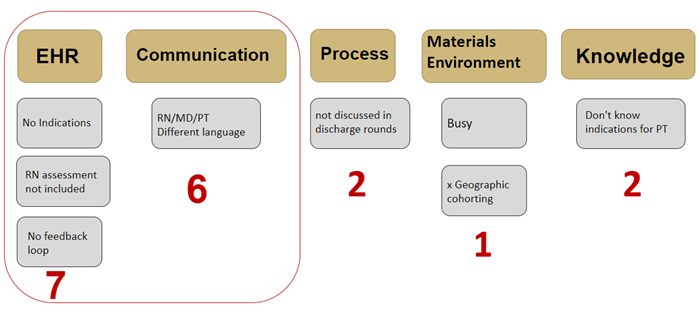

After you have completed the early steps of the Investigate phase, you will likely have many insights into what is causing your problem. Now you want to capture all the factors that contribute (AKA ‘contributing factors’) to your problem in a visual tool and allow for the team to vote on which factors are most important.

There are two commonly used tools for determining the contributing factors: an Ishikawa or fishbone diagram and an affinity diagram. The two yield similar outcomes with the affinity diagram starting with specific ideas that then get categorized into broader affinity groups. The fishbone process begins with broad categories and works toward specific ideas. IHQSE tends to use the latter, although both are acceptable ways to understand your contributing factors. This process prepares you for solution generation. Consider the following steps when you structure your affinity diagram.

- Step 1: Brainstorm what the contributing factors are to the problem.

- This is usually a group event that includes 3-8 people. Fewer than that and you are likely going to miss important insights. More than that will tilt toward chaos.

- Be sure you include multiple disciplines. If your problem includes a certain group, e.g., physicians, you should have at least one involved otherwise you are left to speculate what they think.

- Brainstorm all the factors that may contribute to your problem. Be sure to include things you learned from your voice of the customer, stakeholder interviews, surveys, and process mapping.

- Put each on a sticky note.

- Step 2: Ask ‘Why’ for any factor that requires further exploration.

- If you have any additional insights, put these on more sticky notes.

- Step 3: Sort your sticky notes into themes, or affinity groups.

- These themes can encompass anything that is pertinent for your project work, but suggested themes include: Communication, Process, People, Materials, Technology, EHR, Policy, Environment.

- Step 4: With your team, vote on which of the themes contributes MOST to the problem.

- There are many ways to do this, but one way is to allow everyone to place 3 votes for the theme they think is most important.

- Then add up the votes and the theme with the most is your primary theme.

- Step 5: Use this primary theme to guide your interventions.

- you should target this theme first, since it is causing MOST of the problem. We will discuss this more in the intervention phase of project work.

Example Affinity Diagram:

Revenue – Expenses = Margin

Healthcare margins are typically very narrow. The revenue is high, for sure, but the margins (that is profit) are low. This is because healthcare is very people and supply dependent and both of those entities are very expensive.

For example, the average hospital will make 1-3% profit per year. Many years they may lose money. Thus, there is a constant struggle to maintain financial viability.

There are many potential projects or interventions that an organization can choose to undertake. Generally, the ones that get chosen impact both the value equation’s numerator (quality, safety, equity, experience) and denominator (reducing cost, or increasing revenue—technically in the numerator but will lump here as it references money).

Think of it this way: Without the denominator there is no numerator.

- Your ability to tell the leadership how your work will positively impact finances is your key to get resources. Without resources and support you will not be able to successfully do the project and therefore positively affect the numerator.

- Your ability to tell the frontline staff and providers how this will benefit patients is the key to getting buy-in for the change you are making.

Your job is to speak to both the numerator and the denominator and to present the correct message to both the leadership and the frontlines.

To do this effectively, you first need to know what ‘the business’ cares about. Your executive stakeholder should be included in the voice of the customer activity. When you meet with this stakeholder early in your project work, ask them: What metrics are you focused on? What are you worried about? What is important to you?

The 4 steps of creating an effective business case are:

- Step 1: What are you trying to do?

- You need to know exactly what you’re trying to do with your project work, in a simple statement that you can share with the executive leadership and the frontlines. This is a version of your aim statement.

- Example: Reduce length of stay by 1 day for all patients in the hospital in the next year.

- Step 2: What is the benefit?

- Why would anyone care about this work?

- Start by listing all the potential benefits if your project was successful. Many of these will be non-financial. That’s okay, write them done. You’ll use these when you message to the staff and providers.

- For example: if you shorten length of stay for all inpatients:

- You’ll have less iatrogenesis

- You’ll have happier patients who get home sooner

- The staff/providers will be happier because the care is more streamlined

- For example: if you shorten length of stay for all inpatients:

- However, you must have some examples of the financial benefit of the work.

- For example: if you shorten the length of stay for all inpatients:

- You reduce costs versus a fixed DRG payment from Medicare.

- You create beds that can house new patients therefore increasing revenue.

- For example: if you shorten the length of stay for all inpatients:

- Step 3: How do I show the benefit?

- Consider a formula, with numbers (they can be approximate!) that captures your benefit from the last step. For example, if you reduce length of stay by 1 day, you’ll need the following numbers:

- Cost of 1 hospital day = $1000 (this is a generally accepted estimate)

- Revenue generated by new patient in that bed = $1000 (this is a generally accepted estimate)

- Number of patients impacted = 200

- Number of hospital days saved = 200

- Financial benefit = 200 hospital days x $1000 revenue per bed day + $1000 cost saving per day = $400,000

- Step 4: What data do I need?

- Ensure all data items above are included in your data collection plan, in addition to your process, outcome, balancing and structural metrics.

- A very common error in QI work is to fail to measure the elements you need to show the financial benefit. You need to capture these and include in your data plan.

Return on Investment (ROI) is a way to show the financial benefit of a project. For every dollar invested in the work, how much will you return. It’s a simple way for leaders to compare the potential benefit of one project versus another. In general, your project should yield at least a 3:1 ROI. The closer you get to 10:1 the more likely you are to get the investment you need.

- ROI = $ benefit - $ invested/$ invested.

- Example

- $100,000 invested

- $400,000 benefit

- $400,000 - $100,000/$100,000 = 3:1 ROI

Once you have a business case with an ROI you should plan to share it with your executive stakeholder. It allows them to know WHAT you are doing, WHY you are doing it, and allows them to give you resources to help support you. It also creates an IOU, such that you can return to them when your project is complete and show them the actual benefit of the work.

To be clear there are benefits of all projects that cannot be captured financially—safety, harm reduction, quality, etc. You should definitely speak to these BUT if you lack a financial case, you are less likely to get support to improve the safety, harm and quality. In other words, without the denominator, there is no numerator.

The aim statement captures your project goal, and is, essentially a goal. It should stem directly from your Problem Statement. It should be SMART:

- Specific: What exactly are you changing

- Measurable: What metric (usually a process metric) will you be measuring and impacting

- Achievable: Is your goal realistic?

- Relevant: Do stakeholders care about your problem?

- Timebound: When are you going to fix this problem by? Choose an end date.

Aim statements typically center on a change to a process measure. You should include your baseline data as well as your goal data.

You should toggle the amount of change AND/OR the time for change to ensure that your aim feels doable to those you are leading. It is much better to aim for a small improvement over a small timeframe than a large improvement over a large timeframe.

- For, example, while improving diabetic Alc of < 6.5% from 44% to 100% is admirable, it is likely to take you a long time (if ever) to achieve that.

- Rather, use a small change (44% to 50%) over a small time (6 months) and use that success to build momentum (step 7 of change management in the eQuip phase--use credibility for more change) for even bigger change.

The aim statement allows your team and your stakeholders to understand where you are going, and what the goals are. It creates accountability.

Examples:

- We will reduce oversedation by 50% in the Cardiac ICU, as measured by RASS scores by August, 2024.

- We will reduce inappropriate consultation of PT in the hospital from 37% to 10% by August, 2024.

- We will increase the percentage of diabetic patients having an Alc check every 6 months from 37% to 60% by August, 2024.

You may find that you have multiple aims and this is okay. Sometimes there will be a global aim statement with 1or 2 specific aim statements.

Pro Tips

These materials are developed and created by IHQSE faculty and are the property of the Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety and Efficiency (IHQSE). Reproduction or use of these materials for anything other than personal education is strictly prohibited. Please contact IHQSE@cuanschutz.edu for questions or requests for materials.