CU Anschutz Obstetrics and Gynecology History

Left: The first University Hospital was opened in 1885 and accommodated 30 patients. Middle: 1883, University of Colorado’s Medical Department in Old Main on the Boulder Campus. Right: By 1888 the School had its own building, Medical Hall.

The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Before its Golden Anniversary

Written by Stuart P. Gibbs, in 1996

Introduction

Perhaps no specialty of medicine has had so much change in the last 50 years as obstetrics and gynecology. Huge strides have been made in the realms of research, patient care and education not to mention the flourishing (or outright creation) of the subspecialties of perinatology (maternal/fetal medicine), reproductive endocrinology and oncology. The practice of obstetrics and gynecology today, compared to five decades ago, is hardly recognizable. The University of Colorado Anschutz Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology has played a more than significant role in the progress and developments. Among its pioneering contributions to the field:

- First long-term follow-up study done on premature infants.

- Landmark discovery that premature labor was linked more closely to socioeconomics than physiology − one of the first times such a connection was discerned.

- Development of diagnostic ultrasound — and the first research publication on it in America.

- First use in the United States of estradiol determinations during pregnancy as a method of monitoring maternal/fetal health.

- First course in the country in surgical technique and dog surgery taught to residents of obstetrics and gynecology.

- World’s first Division of Perinatal Medicine.

- Development of the “gas exchange” model of how gases are transferred across the placenta from mother to fetus.

- Discovery that mothers exposed to high altitude gave birth to children of lower birth weights which led to, among other things, the mandatory pressurization of commercial airlines.

- Pioneering work in understanding the relationship of synthetic estrogens and antiestrogens with tumors of the breast and endometrium.

- Development of strategies for prevention of infection-related pre-term birth and neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis.

- First successful treatment of a fetus with hydrocephalus.

- First clinical program funded by the National Institutes of Health to combat thalassemia with stem cell transplants.

- Development of innovative, cost-effective methods of in vitro fertilization, such as micromanipulation.

- International leadership in research in contraception and control of abnormal bleeding.

It is no coincidence that these developments, and hundreds of others, occurred after the establishment of a full-time faculty at the University. The history of the obstetrics and gynecology faculty is a fast-moving and fascinating one. However, to understand how great the change was, it is helpful to begin before the faculty was created.

The Department Before Full-Time Faculty

Although there has been a Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Colorado in some form or another since 1866, there has been a full-time faculty for only the last 50 years. For more than half of the department’s existence, teaching and instruction were in the hands of volunteer physicians from the community. There were respected physicians with their own medical practices who graciously donated their time and energy week after week to tend to indigent patients, teach medical students and residents and, in some of their remaining hours, research. In 1945, the year before the establishment of the full-time faculty, the department was run by Dr. Clarence Ingraham, who himself was a volunteer, taking time out of his busy Denver practice to handle the administrative duties of the department and oversee the volunteer faculty.

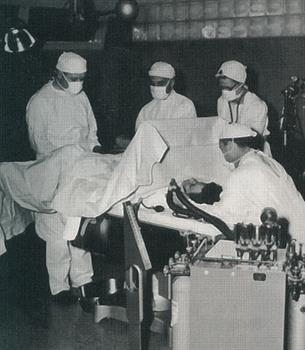

The hospital, then called Colorado General, was still at its old location, on the south side of Ninth Street at Colorado Boulevard, where Denison Memorial Library is now. The obstetrics ward was on the fourth floor and consisted of some examining tables, two small delivery rooms and one big ward with 18 beds that could be separated by canvas drawsheets.

Many patients did not deliver at the hospital. Instead, the hospital ran a home delivery service staffed by senior medical students and volunteer nurses. Established in 1927, the service ran for the next 20 years without a single maternal death — an exceptional record for that time.

One might wonder, however: Surely, a department couldn’t run entirely staffed by volunteer doctors. Who saw to patients who arrived in the middle of the night? Who was on call? The answer, simply put, is: the chief resident.

In 1946, the chief resident was a young man named Dr. Jack Simmons whose medical education, like that of many men his age, had been interrupted by a stint in World War II. He was the only resident in obstetrics and gynecology, and he was on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week. He lived at the hospital, tended all patients, ran the home delivery service and notified the faculty of emergency cases. He was paid $25 a month.

The resident and medical students learned by doing. The volunteer doctors allotted them time (“I’ll give you four hours on Thursday”) to demonstrate surgical techniques. There was no formal on-call system. In an emergency, Jack would call Dr. Ingraham. If Ingraham was unavailable, he then would work his way down the list of doctors. The volunteers did not make rounds after surgery — the chief resident did — and, thus, Jack could occasionally go 4–to–7 days without seeing a senior staff person.

In those days, Colorado General Hospital was entirely funded by the state. It was responsible mostly for indigent patients, those who couldn’t afford to go to private hospitals. It wasn’t unusual for a patient who had never been treated once in pregnancy to show up on the doorstep, ready to deliver. No one was ever turned away.

If a patient actually did show up in the early stages of pregnancy, there was only one noninvasive way to determine whether or not she was actually with child, the old rabbit test: inject 10cc’s of her urine into the vein of a virgin female rabbit’s ear and wait to see if the rabbit ovulated. This test was notoriously inaccurate, however. In August, 1946, the Journal of the American Medical Association quoted Dr. Ingraham on his ‘Colorado Pregnancy Test’ “Wait nine months and see what happens.”

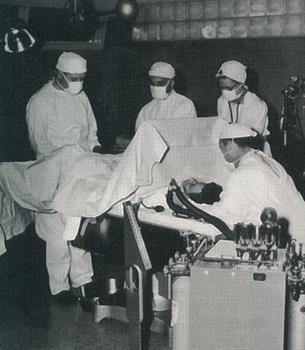

There was no truly accurate way to judge the size of the fetus, either. Abdominal x-rays could be used, but only after 4 1/2 months. (The bones hadn’t ossified enough to show up otherwise.) Any Pap smears taken had to be sent to the East Coast to be interpreted. The Rh factor was unknown. And, there were no blood banks. In the case of an emergency cesarean section, it could take up to one and a half hours to line up one of the hospital’s two surgical rooms — longer if it was a holiday because it became considerably more difficult to track down staff members. To get the necessary blood, the chief resident would have to line up neighbors, nurses, possibly even the janitorial staff for donations. The surgery was deemed extremely dangerous. If the cesarean rate was more than 3.5%, the American Hospital Association considered that to be a “deviant” rate and would come to investigate.

Between April 1946 and 1947, 551 babies were delivered at Colorado General Hospital. There were approximately 15 cesarean sections. After vaginal delivery, patients stayed in the hospital 6-to-8 days, often spending the first five-to-six days in bed. It also was during this time that the home delivery service was terminated, after two medical students went off to make a routine delivery and vanished for 12 hours. It turned out that they had diagnosed twins for the woman, taken her to St. Luke’s Hospital and simply forgotten to report in. They had caused so much worrying at the hospital — particularly for Jack Simmons — that the program was terminated.

The “Birth” of Full-Time Faculty

Obstetrics

and gynecology wasn’t the only department without a full-time faculty. Although there were administrators and support staff, every department in the medical school was staffed by volunteers until the 1940s. The basic curriculum had changed very

little since the 19th Century.

Obstetrics

and gynecology wasn’t the only department without a full-time faculty. Although there were administrators and support staff, every department in the medical school was staffed by volunteers until the 1940s. The basic curriculum had changed very

little since the 19th Century.

In 1936, the school received some hard knocks when it was inspected by a committee responsible to the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals of the American Medical Association. It was chaired by Dean Weiskotten of the medical school at Syracuse University. The 64 medical schools in the country were ranked, and their departments were evaluated from one to ten, with one being the highest grade. The committee did not sugar-coat its reports: Colorado received a number of deficiencies. While the administration and the deanship were given high marks, financial support was found to be completely inadequate, ranking an eight.

Worse, however, were the severe marks for the clinical departments, all of which were found to be inferior to the pre-clinical ones. Obstetrics was given a rating of six, but it fared considerable better that the Department of Medicine, which ranked a nine. Only pediatrics had an “acceptable” mark receiving a rank of four.

The fundamental problem, according to the committee, was the clinical faculty were not familiar with the work being done in their departments. Teaching was uncoordinated. A recommendation was made for the establishment of a full-time faculty.

When an evaluation committee from the Association of American Medical Colleges dropped by in 1940, little had changed. Although the departments were spared the 1 to 10 rankings, the clinical years once again received the most criticism. The national committee reiterated its strong recommendation for a full-time faculty: “The lack of full-time clinical instructors prevents research in these departments.”

Before steps could be taken to rectify this situation, however, World War II broke out, and many of the students — as well as much of the part-time faculty — were recruited. When the war ended, Dr. Ward Darley had taken over as dean. A private practitioner who had been educated at the medical school, Dr. Darley had been encouraged to join the faculty by Dean Rees, who was a patient of Dr. Darley’s for coronary artery disease. In 1943, Dr. Darley agreed to serve as a full-time teacher in the School of Medicine with two stipulations: pay of $4,800 a year, and the ability to continue seeing private patients. Dr. Darley worked out so well that a new position of assistant dean was created for him in 1945. When Dean Rees die suddenly, Dr. Darley took over as acting dean.

Dr. Darley’s primary objectives were hiring full-time faculty and, thus, improving the residency system. Many students and residents were returning from the war, eager to finish their training, and the creation of the G.I. Bill provided new funds for education. One of the first full-time faculty brought aboard was in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Dr. E. Stewart Taylor, who eventually would run the department for the next 29 years.

E. Stewart Taylor

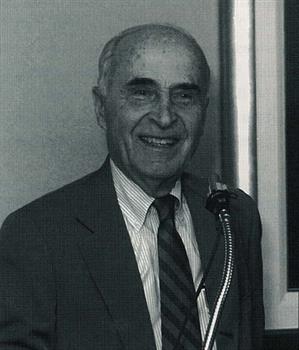

It

would be impossible to do justice to the history of the department without giving huge credit to Dr. Taylor. Indeed, it would be hard to find a more respected figure in the annals of the entire medical school. Those who worked under him fondly

recall him as a “true gentleman” with an impressive commitment to education and research. Furthermore, he was a respected surgeon who had done a great amount of trauma work in World War II. Dr. Taylor came to Denver from Long Island

College Hospital to go into private practice with Dr. Ingraham. Dr. Alfred Beck, Dr. Taylor’s chairman and mentor at Long Island, had recommended him highly and Dr. Taylor thought Denver would be “a nice place to live”

for his wife and young twin children. Dr. Taylor began practicing with Dr. Ingraham in January 1946, and he was quickly appointed to the volunteer faculty. By September, he became the first full-time faculty member in the department’s

history.

It

would be impossible to do justice to the history of the department without giving huge credit to Dr. Taylor. Indeed, it would be hard to find a more respected figure in the annals of the entire medical school. Those who worked under him fondly

recall him as a “true gentleman” with an impressive commitment to education and research. Furthermore, he was a respected surgeon who had done a great amount of trauma work in World War II. Dr. Taylor came to Denver from Long Island

College Hospital to go into private practice with Dr. Ingraham. Dr. Alfred Beck, Dr. Taylor’s chairman and mentor at Long Island, had recommended him highly and Dr. Taylor thought Denver would be “a nice place to live”

for his wife and young twin children. Dr. Taylor began practicing with Dr. Ingraham in January 1946, and he was quickly appointed to the volunteer faculty. By September, he became the first full-time faculty member in the department’s

history.

Dr. Taylor quickly began to make changes. First and foremost was the creation of a four-year, graded residency program, designed to follow a rotating internship. There would be only one resident in every class. Since there was only one resident in the department at the time, three others were brought in from the University of Chicago — one for each remaining year — to fill in the gaps.

Denver General Hospital also had a residency program at the time and, in 1948, an agreement was made to rotate residents, effectively doubling the number of residents each hospital got to educate.

In April 1947, Dr. Ingraham decided to retire as chairman, becoming professor emeritus. Dr. Stewart Taylor was the only choice to take his place, and soon became professor — as the first paid chairman — of the department. At the time, Dr. Taylor also was serving on the search committee, given responsibility for recruiting other doctors to the University to serve as full-time chairmen or faculty.

Just as important as restructuring of the residence was his development of a strong research department. Dr. Paul Bruns, a young doctor with a strong interest in research, was recruited from John Hopkins in 1948. Dr. Bruns, too, had been highly recommended. According to Dr. Taylor, the chairman there had told him that Dr. Bruns was “the only resident I ever had who could get along with everybody.” As the story goes there was a staff nurse who was a thorn in the side of everyone at Hopkins, but even she got along with Dr. Bruns.

It

is not uncommon for doctors who trained in obstetrics and gynecology at CU to say that they chose the school solely because of Drs. Taylor and Bruns. Both men were more than teachers: they were mentors and role models. Dr. Watson Bowes, who trained

under both men in the 1960s and later became a faculty member, notes that they were “models of excellence” who set the example of how a doctor should behave. The residents toed the line, not out of fear of punishment, but out of respect

for their teachers: “No one wanted to do anything that would embarrass them.”

It

is not uncommon for doctors who trained in obstetrics and gynecology at CU to say that they chose the school solely because of Drs. Taylor and Bruns. Both men were more than teachers: they were mentors and role models. Dr. Watson Bowes, who trained

under both men in the 1960s and later became a faculty member, notes that they were “models of excellence” who set the example of how a doctor should behave. The residents toed the line, not out of fear of punishment, but out of respect

for their teachers: “No one wanted to do anything that would embarrass them.”

Dr. Fred Battaglia, who was recruited to the University by Dr. Taylor, recalls Dr. Taylor as a “masterful surgeon” who never lost his cool. After so many hours doing trauma surgery in adverse conditions during the war, it seemed that “nothing frightened him in the O.R.”

Perhaps Taylor’s greatest contribution, not just to the University or the department, but to the entire field of obstetrics and gynecology, however, was what evolved from his great foresight, innovative teaching and commitment to understanding and preventing prematurity: development of the field of perinatology.

The Road to Perinatology

In 1946, it was not uncommon in hospitals for there to be a strict boundary between the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology and the Department of Pediatrics, although it varied as to exactly where the line was drawn. In most hospitals, the postpartum nursery was supervised by obstetricians; pediatricians only were called when infants were acutely ill. In very few hospitals, however, did the departments combine efforts to better understand the relationship of mother and child during — and after — pregnancy.

At Long Island College Hospital, where Dr. Stewart Taylor had trained, pioneering strides in the care of the newborn were being made by making that care a collaborative effort between departments, a tradition that Dr. Taylor intended to establish at Colorado General Hospital. Fortuitously, the chairman of Pediatrics was Dr. Harry H. Gordon, who have been hired from Cornell as a full-time faculty on exactly the same day as was Dr. Taylor. At Cornell, there had not been much collaboration between obstetrics and pediatrics, a situation which had greatly frustrated Dr. Gordon.

The two men quickly became fast friends. In fact, they shared an office in the early years, running their respective departments out of a common room. Both doctors had a primary clinical interest in the premature infant, particularly in trying to determine what caused prematurity and trying to prevent it. At Colorado General, the perinatal mortality rate was around 4 percent, and it had been determined that 75% of those cases were associated with prematurity. Drs. Taylor and Gordon felt that getting a better understanding of prematurity necessitated collaboration between their departments, and it was arranged for the pediatricians to have knowledge of prenatal events so they could be prepared to deal with problems in the newborn period.

Dr. Gordon applied to the U.S. Children’s Bureau and the Colorado Department of Health for funds to establish a Premature Infant Center as a combined request from pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology. The grant was awarded in 1947 with some unusual features: it provided for several beds on the obstetrical service for long-term prenatal care of patients with complications of pregnancy, the salary of an obstetrician whose interests were primarily in the field of preventative obstetrics, and an intensive care nursery, along with necessary nurses and pediatricians. The Premature Infant Center, located adjacent to obstetrics in the hospital, quickly became a community and state-wide referral center.

Around this time, Colorado Department of Health began to notice an alarming trend. All birth certificates were filed in Denver, and comparisons of the registered birth weights of babies at higher altitudes. Dr. Bruns and Dr. John Lichty decided to investigate, despite the proclamation of then-governor Johnson that it was common knowledge that everything was simply born smaller at higher altitudes: “Anybody knows that,” he said. “Even the gophers are smaller up there.”

To the surprise of many, Drs. Bruns and Lichty discovered that the governor was actually right. After careful research, it was discovered that babies born in Leadville, at 10,000 feet above sea level, were an average of 400g lighter at birth that those born in Denver, whose infants, were 400g lighter than those born in Los Angeles. The result was a new classification of “low birth-weight babies.” The infants weren’t premature at all, they were simply small.

Meanwhile, Drs. Taylor and Gordon had recruited Dr. Lula Lubchenko, a Russian-born pediatrician. Her family had fled Russia for political reasons in 1917 on the Trans-Siberian railroad, and eventually came to Denver. Dr. Lubchenko had trained at CU, where she had developed an interest in prematurity. She conducted the world’s first long-term study of premature infants, which led to landmark work on the identification and classification of the low birth-weight infant for gestational age.

From this, she developed an intrauterine weight chart that is still in use.

To gain a better understanding of prematurity, Drs. Taylor and Bruns decided they needed a greater understanding of the physiology of normal and abnormal labor. Dr. Bruns fell the task of studying estrogenic substances in what ended up amounting to hundreds of gallons of urine. It was soon discovered that prematurity was indeed linked to maternal illnesses — and something even more surprising. During their clinical research, the doctors were “constantly struck with the fact that prematurity was a disease of the poor.”

The evidence was startling. At Denver General Hospital, which tended to the city’s indigent, the incidence of prematurity was 21.5 percent in the late 1940s. At the University hospital, the incidence was only 10 percent; at private hospitals, it was only 5–to–7 percent. Thus, in Dr. Taylor’ own words: “The conclusion became inescapable that socioeconomic factors were very important in the cause of low birth weight infants.” Worse, these factors could not be corrected simply by good prenatal care: “A lifetime of poor dietary habits could not be corrected in nine months.”

The discovery that the roots of the prematurity went farther than mere physiology was startling and revolutionary. The federal government was extremely pleased with the research; whenever the U.S. Children’s Bureau went to Congress to ask for more money, they pointed to the Colorado program as the jewel in their crown. As a direct result of the research done in Colorado, the federal government introduced various programs to improve maternal and infant care which included contraception, sterilization, child spacing and better total medical care. As a result, there were significant drops in perinatal death rates, complications of pregnancy and the rate of prematurity nationwide.

The next stage of the development of perinatology involved an ever-growing number of faculty, prominent researchers — and sheep.

The work being done at Colorado in prematurity and ultrasound diagnosis pointed in one direction: the relationship between the mother and the fetus during pregnancy had to be better understood. In 1965, the department had just received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to continue research into the causes of prematurity. Dr. Fred Battaglia was recruited from pediatrics at Johns Hopkins. Former residents Drs. Frederick Fox and William Droegemueller also came aboard. And when Dr. Paul Bruns left to become chairman at Georgetown, Dr. Ed Makowski was brought in from the University of Minnesota to replace him.

Sheep were determined to be the perfect animals for maternal/fetal research for several reasons. The uterus isn’t very irritable; sheep fetus is about the same size as a human fetus; and sheep don’t have a single placenta. Instead, they have a mass of about 90 separate placentas called cotyledons, which allowed one or two to be operated on without threat of pregnancy loss. Furthermore, the sheep themselves were surprisingly complacent. Catheters were attached to the mother and fetus and the sheep adapted easily, making for considerable technical ease of research.

At the time, with only three full-time OB-GYN faculty (Dr. Battaglia was technically in pediatrics), the strains of teaching, researching and tending to patients would sometimes be overwhelming. Sometimes they worked until 4 or 5 in the morning and were back to work at 7 AM. Exhausted from such a long schedule, Dr. Makowski once fell asleep at the dinner table, face down in his mashed potatoes and gravy. “If it hadn’t been for my wife”, he says, “I could have drowned.”

The sheep model was actually developed at Yale, but it was Colorado where an astounding amount of the research was done. Drs. Battaglia and Makowski and both studied the sheep model under Dr. Donald Barron at Yale and were quite knowledgeable in the technique. A sheep lab was established at Fitzsimons Army Medical Center, where dozens of sheep were under observation at any given time. Among the topics they investigated were the amount of blood flow across the placenta, the metabolization of oxygen, glucose and amino acids, and the effects of high altitude on the fetus.

The sheep research often required impressive innovations. Radioactive microspheres were injected into the bloodstream of the mother or fetus and tracked to see where the blood flowed. On occasion, sheep were sedated, shaved and run through the ultrasound machine. To research the effects of high altitude, however, the approach was somewhat more basic: the University simply acquired a truck.

The sheep would be loaded into the truck and driven up to the top of Mount Evans, more than 14,000 feet above sea level, on the highest auto road in the United States. At the top, blood samples would be taken to determine the effects of the decrease in oxygen.

One day in the late sixties, Dr. Makowski set off for the top of Mount Evans with a truck full of sheep, unaware that a storm was raging at the top of the mountain. On the way up, the temperature suddenly plummeted, and snow began to fall. Dr. Makowski continued to the top of the mountain and discovered, to his surprise, that all his sheep had gotten wet and cold…and they had all frozen stiff in the back of the truck. Not much later, Dr. Battaglia was startled when Dr. Makowski arrived back from his research trip far earlier than usual.

“What happened?” Dr. Battaglia asked.

“All the sheep froze solid.”

“Damn it!” Dr. Battaglia quipped. “You were just supposed to freeze the blood samples, not the entire sheep!”

The results of the research done at Colorado during this time were of major importance in understanding the development of the fetus. Among the results that affect us to this day: It was determined that even a brief time spent at high altitudes affected the mother and fetus, increasing the chances of miscarriage and abortion. At the time, passenger planes in the United States routinely went to altitudes even higher than 14,000 feet above sea level, but without pressurizing their cabins. Once it became evident what risks this posed to pregnant women, airlines soon became required to pressurize their cabins during flights.

In the past, doctors have considered the administration of oxygen detrimental to delivering mothers and newborns. At Colorado, it was determined that this was not the case, and that oxygen was very helpful to mother and fetus if administered properly.

It was determined that the fetus metabolizes amino acids for approximately one-quarter of its energy requirements. If the mother is malnourished or has a chronic disease or preeclampsia, this major source of fetal nourishment is significantly reduced. Often, these infants will do better out of the uterus than in it, even if the pregnancy is premature.

It was of great importance to have a neonatologist present in the delivery room to immediately examine the newborn for any acute clinical problems.

Such discoveries had a dramatic effect on the survival of the newborns. In the 1950s, extreme low birthweight babies (500 - 1500g) only had a 20 percent chance of survival; those who survived had a 70 percent chance of a neurological handicap. By the 1970s, those same babies had a 71 percent survival rate. The University had the second lowest neonatal death rate in the United States.

Eventually, so much of the obstetrics and gynecology and pediatrics faculty were working together that Dr. Taylor and Dr. Kemp, then the head of pediatrics, felt the time had come for a radical new idea: they applied to the executive faculty and eventually the University regents — to create the first interdepartmental division at the University of Colorado. Their request was approved.

And so, in 1970, the world’s first Division of Perinatology was created, with Dr. Battaglia as its head.

Of course, those involved point out that the division had been around for some time, but simply in an “unofficial” capacity. The cooperation between departments was still well ahead of its time. According to Dr. Makowski, “It was so unusual that many colleagues said it wouldn’t last.”

Instead, the rest of the world followed, although it took some time for this to occur. The impressive collaboration between these departments, which lead to so many great researchers making great contributions, was, in Dr. Makowski’s words, “The best event that could have occurred in the history of perinatal medicine.”

Although the areas being researched have shifted during the years, sheep still are being used for research at Colorado. (Rhesus monkeys were used briefly, but the closest primate research center is in Oregon, and the commuting costs became too extreme.) As Dr. Battaglia says, “The ‘hot’ research areas change during the years.” Currently, studies are being done in nutrition and metabolism, vascular biology and new techniques in imaging research.

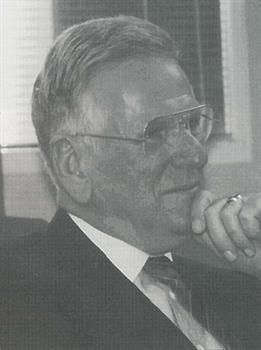

Edgar L. Makowski

In

September, 1976, Dr. Taylor stepped down after 29 years as chairman of the department — easily a record among full-time faculty at the entire University. In fact, Dr. Taylor had outlasted the original chairs of all the other departments —

most of whom he had recruited to Colorado in the first place! Always an active man, Dr. Taylor “retired” to private practice.

In

September, 1976, Dr. Taylor stepped down after 29 years as chairman of the department — easily a record among full-time faculty at the entire University. In fact, Dr. Taylor had outlasted the original chairs of all the other departments —

most of whom he had recruited to Colorado in the first place! Always an active man, Dr. Taylor “retired” to private practice.

The obvious choice for succession was Dr. Makowski, who soon became the department’s second chairman. Those who worked with him and under him are quick to point out that he was an exceptional clinical researcher. As chair, Dr. Makowski made research only the third of his three objectives. The first two were making sure that patients received outstanding clinical care and that there was a major commitment to the educational programs.

One of Dr. Makowski's first initiatives was to attain better fetal monitoring equipment for the department. Despite the fact that ultrasound had been invented at Colorado and almost all the original research had been done on it here, obstetrics and gynecology didn’t actually have an ultrasound machine. Dr. Makowski made his acceptance of the chairmanship contingent upon the acquisition for one.

Under his leadership, the residence nearly doubled in size from five residents to the current size of nine per class. As they were now working at Denver General and Rose Hospitals, the work load was overwhelming for just five. Under Dr. Makowski, the residency flourished, and residents were able to spend more time studying the intricacies of the specialty.

The American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology had formulated new subspecialties in 1972: maternal/fetal medicine, reproductive endocrinology and gynecologic oncology. Residents were encouraged to become experts in fetal monitoring, genetics and pathology.

And,

of course, under the eye of a man with such a strong research background as Dr. Makowski, research flourished at Colorado with the addition of new faculty and residents. Work was done on post-dates pregnancies, bed-rest after twins gestations, pregnancy

after kidney transplant, ablation of the endometrium, mixed carcinomas of the endometrium and intra-uterine transfusions of the fetus.

And,

of course, under the eye of a man with such a strong research background as Dr. Makowski, research flourished at Colorado with the addition of new faculty and residents. Work was done on post-dates pregnancies, bed-rest after twins gestations, pregnancy

after kidney transplant, ablation of the endometrium, mixed carcinomas of the endometrium and intra-uterine transfusions of the fetus.

A highlight combining research and surgery was the first successful treatment of a fetus with hydrocephalus. This complex technique required the collaboration of Drs. Clewell, Meier and Bowes from obstetrics and gynecology as well as doctors from radiology and The Children’s Hospital. It involved, among other things, the diagnosis of hydrocephalus by ultrasound, the development of a special shunt to drain cerebrospinal fluid and the surgical expertise to insert the shunt in the head of the fetus. This paved the way for a new era of complex, collaborative obstetrical care.

Dr. Makowski’s far-ranging interest affected not just his department, but the entire hospital. For example, his leadership was important in revamping how faculty practice funds were divided among departments. For a long time, the faculty had no idea how much money they were bringing in, or how much their department was getting back. All of the money went into and came out of a mysterious “Faculty Practice Fund.” Dr. Makowski chaired a committee that reorganized the fund so that the money doctors made came back to their own departments.

Dr. Makowski also was instrumental in changing the name of the hospital from Colorado General. It was his belief that the hospital’s name should mention its connection to the University; talking to random people on the streets of Denver had proved that many people were unaware that Colorado General had any affiliation with University of Colorado. Dr. Makowski made his point to the hospital board, and in 1979, the name was changed from Colorado General to University Hospital.

It's Been to Obstetrics What Penicillin was to Medicine

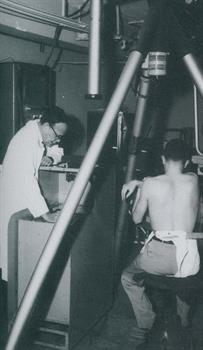

Ultrasound, originally, was the brainchild of CU medical student, Douglas Howry. The idea originally came to him as he was being shipped overseas as an infantry officer in World War II. He became fascinated by the sonar system on the transport ship and got the idea that it had diagnostic possibilities as well.

When he returned from the war, Howry enrolled at Colorado as a medical student, but he was so busy concentrating on his new invention that he didn’t concentrate on his courses and flunked his first year. At the time, however, Dr. E. Stewart Taylor was the chair of the Promotions Committee and, convinced that young Howry was on to something, recommended that he be given another chance. Howry was allowed to graduate in five years, rather than four.

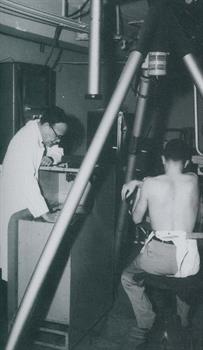

By

1950, Dr. Howry’s invention caught the eye of Dr. Joseph Holmes from the Department of Medicine. Dr. Howry took a leave of absence from his residency training to work with Dr. Bouslog from radiology, and the first ultrasonic scanner was constructed

in Dr. Howry’s basement. The earliest models were cumbersome affairs. In one, the “somascope,” the patient sat in a water tank made from an old B-29 gun turret and held lead weights to keep from floating. Surprisingly, one of

the first uses for ultrasound wasn’t diagnostic,

By

1950, Dr. Howry’s invention caught the eye of Dr. Joseph Holmes from the Department of Medicine. Dr. Howry took a leave of absence from his residency training to work with Dr. Bouslog from radiology, and the first ultrasonic scanner was constructed

in Dr. Howry’s basement. The earliest models were cumbersome affairs. In one, the “somascope,” the patient sat in a water tank made from an old B-29 gun turret and held lead weights to keep from floating. Surprisingly, one of

the first uses for ultrasound wasn’t diagnostic,

but therapeutic. It was used to relieve the pain in arthritic joints by heating them via sound waves.

In the 1950s, Bill Wright, a member of Dr. Holmes’ research staff, left to start Longmont Physionics, a company dedicated to building better ultrasonic scanners. Dr. Wright stayed in almost constant contact with the medical school, which advised him on how to make more and more improvements in the device. Many original experiments were done by floating organs or other body parts in a horse trough and emitting sound waves through the trough to map the organs.

Oddly enough, despite Dr. Taylor’s original support, obstetrics and gynecology was not very involved with ultrasound throughout the 1950s. The first studies were actually done in Scotland, by Dr. Ian Donald. In 1962, however, Dr. Horace “Tommy” Thompson, a graduate of the University and a member of the volunteer faculty, came upon an article of Dr. Donald’s and was stunned to discover that the revolutionary device Dr. Donald’s research was based upon had actually come out of a CU brain trust.

Dr. Thompson went to Drs. Taylor and Holmes, eager to get involved in ultrasound research. Dr. Homes arranged for some grant money to be funneled to Dr. Thompson, and the chief resident, Dr. Kenneth Gottesfeld, was assigned to the project. The

first research done was to confirm Dr. Donald’s research, measuring the biparietal diameter of the fetus. Most of this was done on volunteer patients from the Critteden Home for Unwed Mothers, a Denver charity institution that the University

doctors tended. Critteden proved to be a fine place to perform research: as the patients lived there, allowing Drs. Thompson and Gottesfeld to see them from their first visit until the time they delivered. In 1964, Drs. Taylor, Thompson,

Holmes and Gottesfeld published their first paper on the measurement of the

fetal biparietal diameter by use of ultrasound; this was the first paper on ultrasound published in the United States.

Soon, however, further advancements were made in the technology. The “B-scope” produced a two-dimensional image by using the amniotic fluid in the womb as a conduit, the patient didn’t have to float in a bathtub. The B-scope was a large device mounted on struts attached to the ceiling. Mineral oil was used to couple the sensors to the patient’s body. This version of ultrasound provided wonderful results for years to come. Today, it rests in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Until the development of ultrasound, there had not been a non-invasive way to study the growth of the fetus. Now, on the forefront of the new technology, Drs. Thompson and Gottesfeld worked relentlessly, churning out papers. They measured all structures of the fetus: the sizes of the head, chest, femur to humerus ratio; measured the placenta, and studied tumors of the pelvis. Dr. Gottesfeld was so enthusiastic about his research that he made his family a part of it: when his wife, Joanie, became pregnant, Dr. Gottesfeld spent hours scanning her abdomen, seeking new techniques for diagnosis. On occasion, he even invited his mother over to watch.

Part of what had to be determined was the best way to use this new device. Ultrasound, although safer than radiation, had its theoretical dangers, too. It was well known that if used at levels the Navy did to hunt for submarines, it would kill anything that swam into its path. The diagnostic levels were determined to be thousands of times less and entirely safe. Dr. Thompson also determined that it was helpful to scan patients with full bladders, since this pushed the reproductive organs into better viewing position. In an early manual, he prescribed having patients refrain from urinating until they “felt the urge to void.”

By the 1970s, ultrasound was used routinely in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy to diagnose fetal growth restriction, blighted ovum, abnormally implanted placenta and fetal death in utero. The landmark breakthrough, however, was evaluation of early pregnancy; ultrasound, to this day, provides the only visual means of following the fetus during the first trimester. Ultrasonic techniques proved extremely valuable in ascertaining fetal maturity when the date of conception was unknown.

Dr. Thompson himself reports that, at first, they “couldn’t anticipate how important it would be.” It soon became evident, however, that they were onto something that would change the face of medicine as they knew it. Today, the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) numbers 8,000 members, while the World Federation of Ultrasound Medicine probably has as many as 50,000. Dr. Thompson has served as president of both organizations. “It’s been to obstetrics what penicillin was to medicine,” he says. Dr. Taylor agrees, calling it “the greatest advance in obstetrics in my time.”

The Colorado doctors who pioneered ultrasound became recognized around the world for their expertise, and were highly sought after to lecture and educate. Still, their loyalty to the University remained great. Even while in private practice, Dr. Gottesfeld would read ultrasound with residents every day.

Today, Colorado continues as a world leader in ultrasound research. Dr. John Hobbins, who came to the department in 1991 and served as chief of obstetrics, is a world-renowned expert in prenatal diagnosis and also has served as president of AIUM.