Module 4: Leading People

Action Plan

Background

- Resistance is often perceived as an inconvenient barrier to smooth implementation of a plan or new way of doing things.

- In reality, engaging in any sort of change will evoke resistance as a natural outcome of the leadership effort. Thus, navigating resistance more effectively is a key leadership skill.

- David Rock's SCARF model is based on neuroscience regarding the underlying emotional responses people have when experiencing change and common sources of resistance.

- When facing skepticism from an individual, try to uncover and name (for yourself and the other person) the element of the SCARF model driving skepticism.

- Status

- Certainty

- Autonomy

- Relatedness—to my job/goals/values vs. to my cherished relationships

- Fairness

- Decide whether to address that source of skepticism directly or pivot to “topping up” another element of the SCARF model.

- If directly addressing a SCARF domain, discuss with the other person how you can address it together.

- E.g., “It sounds like you are worried this new process will create more hassle and chaos in your daily work (certainty concern). Let’s work together to make sure the process works smoothly and you know exactly what to expect (top up certainty and autonomy).”

- If pivoting to another SCARF domain, acknowledge the other person’s concern and then direct attention to “topping up” another domain. E.g.,

- “It sounds like your group feels the way in which this initiative has unfolded is deeply unfair (fairness concern).”

- “I’m sorry things have played out this way (acknowledge).”

- “Let’s look at how re-engaging now could position you all as leaders (pivot to status).” OR

- “Let’s work together to identify ways in which your group can have more autonomy in shaping the current phase of implementation (pivot to autonomy).”

- Change invokes an inherently social psychology – separate from the change roadmap that supports any change initiative.

- Not all people encountering something new will perceive and react to it in similar ways.

- People affected by the change are often talking to peers about it more than they spend time engaging with leaders or the official communications about change.

- Good leaders vary their engagement approaches to engage with diverse reactions to change.

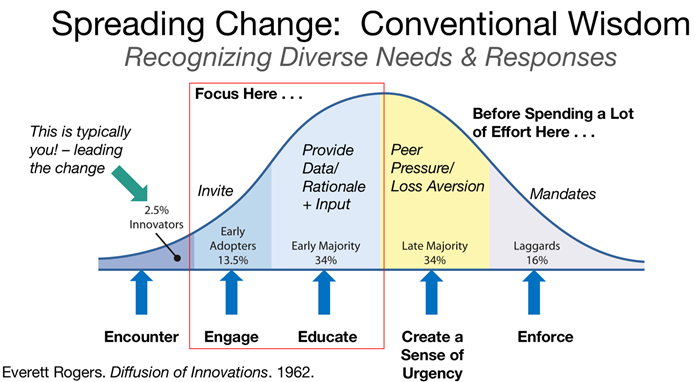

- Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Curve describes common reactions to change, along a spectrum of feeling/thinking that people experience when contemplating something new/different.

- Building an effective guiding coalition requires inviting/engaging innovators and early adopters—those who are excited to support the change without much question. Having this group alone will not ensure success because it is a small proportion of the population experiencing the change.

- An effective coalition also requires members of the early majority – skeptics who will prefer not to change because they are already busy, don’t see immediate relevance, or worry that the change will disrupt the status quo in unhelpful ways. This group desires data and strong rationale that support change and will only get on board once these are provided. Often this group also wants local proof of efficacy, not a paper or case study from other organizations.

- Avoid spending significant time when launching a change on convincing the late majority and laggards—the loudest critics. These 2 groups seek to avoid change at almost all costs, and will work to obstruct change regardless of data, rationale, etc.

- After engaging and winning over skeptics in the early majority, create a sense of urgency for the late majority through peer pressure provided by the early majority members who become ambassadors for the change. Late majority fears being left behind by their skeptical peers in the early majority.

- Engage with the laggards last, by creating new rules/policies or forcing functions that require them to adopt the new way.

- Despite held cultural beliefs in Medicine, humans are fundamentally emotional beings.

- The emotional brain tends to process information first, before the prefrontal cortex engages to apply rational, rule-based thinking.

- Leaders must be prepared to engage regularly with emotions directly, rather than using forms of conversation, agenda-setting, group facilitation to “keep emotions at bay” or deal with them after the fact.

- Leaders most commonly respond to emotions by avoiding them, providing technical information related to the issue driving the emotions, getting defensive, or blaming someone else (throwing someone “under the bus”) in an effort to deflect.

- These responses rarely result in diffusing negative emotions, and often exacerbate them.

- A more effective approach is to Recognize and Respond to Emotions first using the acronym PEARLS—statements that directly address emotions before asking questions, moving into problem-solving, provide data/rationale, or offering context.

- Partnership – “Let’s work on this together.”

- Empathy – “I imagine this is frustrating for you.”

- Acknowledgement – “I’m sorry to hear how hard this has been.”

- Respect – “I appreciate the effort you have made.”

- Legitimization – “Others in your situation often feel the same way.”

- Support – “I am going to stick with you through this.”

- An additional tool is Naming – naming the emotion out loud.

- “It sounds like you are worried/sad/angry.”

- Barriers to change take many forms: learning new habits, taking a risk to try a new way, fear of looking incompetent in front of peers/bosses, being initially slower/less efficient at a new task, fear of the unknown, burnout, metrics that incentivize the current approach, peer pressure to conform to the status quo, etc.

- Creating effective change requires helping people overcome barriers as easily and quickly as possible.

- Designing an effective change initiative requires 3 steps related to removing barriers:

- Identify barriers people are likely to encounter before they experience those barriers.

- This needs to be done before a program/change initiative launches.

- Design ways to remove the barriers or minimize the demoralization that occurs when people experience a barrier.

- This also needs to be done prospectively as much as possible.

- Set expectations for experiencing successes and barriers at a level that means people will say to themselves, “that was easier/less bad than I thought” when they try the new approach/program.

- Identify barriers people are likely to encounter before they experience those barriers.

- Power and influence are inextricably linked, and yet land differently with people.

- Expressions of power tend to engender a sense of compliance, fear-based response (for fear of retaliatory consequences), and resistance over time.

- Expressions of influence tend to leave people feeling they have a choice to engage on their own terms, and thus are often viewed more favorably.

- While some leadership can be accomplished through use of pure power/authority, in reality most leadership comes through influence.

- Power/authority can be useful for very short-term situations when decisions must occur quickly and time for other influence modes is not available. Repeated use of power diminishes social capital/trust.

- Influence often takes more time to cultivate but tends to increase social capital/trust if used effectively.

- Power Bases is one model for understanding different “levers” a leader can use.

- Positional power bases rely on exercising authority, providing rewards, or administering discipline. These drive short-term compliance and long-term resistance.

- Personal power bases rely on demonstrating goodwill, using expertise, and sharing information to help others. These drive more sustainable commitment.

- Another model of understanding different “levers” is influence modes. These are:

- Increasing formal authority – even without using it, getting a bigger title, position, or budget creates an influence halo effect.

- Centrality – being at the center of important activities, decision-making, or inter-personal networks.

- Autonomy – exercising autonomy in how you accomplish a task.

- Visibility – making your work and its impact visible to others, particularly other leaders.

- Relevance – working on priorities that are highly valued by others/the organization.

- Effort – showing consistent commitment to things assigned to you.

- Track record – developing a reputation for excellence, timely completion, etc.

- Expertise – developing a deep knowledge base on a particular topic.

- Attractiveness – displaying key attributes/skills that are particularly impactful in certain situations (e.g., being a skillful negotiator, someone who can resolve conflict, someone who can inspire others, etc.).

- The most effective leaders constantly seek to cultivate authentic influence, through which they can accomplish their goals, rather than “force people to follow” through use of authority.

- Existing models of burnout and wellbeing cite multiple factors that drive negative experiences of work.

- Often, most of these (e.g., health policy and payment, IT systems in healthcare, social expectations of providers, organizational culture) are beyond the exclusive control of individuals, teams, and even leaders.

- In spite of this, all leaders have sources of agency to infuse their work with actions that support wellbeing and positive culture + effective performance at the same time.

- There is an underlying mindset in much of healthcare that performance and wellbeing are handled separately.

- We drive people through critique/feedback, public display of metrics, setting stretch goals that push people to their limits, and steadfast commitment to “do more with less” for the sake of productivity. This generates suitable performance.

- Then, when people are burned out or at a breaking point, we provide them recovery spaces/activities (team lunch, encouragement to exercise or take time off, a recognition ceremony for hard work, etc.) to re-energize and “reduce the burn.”

- Then we return them to performance-based systems that deplete them. The cycle repeats.

- Neuroscience and positive psychology research support that helping people tap into positive emotions, in small doses frequently during work, is vital to enhancing well-being and performance. These emotions are:

- Joy

- Hope

- Gratitude

- Inspiration

- Awe

- Interest

- Amusement

- Pride

- Serenity

- Love

- Creating a culture of wellbeing and performance at the same time requires focusing on infusing positive emotions into 3 aspects of work (and life).

- Personal/individual habits, lasting a few minutes, that allow one to experience the positive emotions above multiple times a week and ideally multiple times a day.

- Group dialog and leadership acts that drive better culture by allowing people to experience positive emotions (or diffuse negative emotions).

- Tap into Motivation 3.0 more often

- Use powerful questions – open-ended, have no obvious answer the questioner would know in advance, and neutral to slightly positive orientation — more often.

- E.g., “What experience have people had so far with the ADEPT tool?” “What has been a positive surprise this week in our work?” “How might we improve to make things even more effective next time we do a case review?”

- After asking a question or hearing from a group member, use reflective listening before asking another question, providing an answer, offering a solution, or presenting data. Reflective listening = listening without interrupting the speaker and then briefly summarizing the key points the speaker made, using the speaker’s own words.

- Use PEARLS to recognize and respond to negative emotions.

- Design structures and processes to deliberately tap into and highlight positive emotions, not only efficiency and outcomes.

- When working on any process, ask people not only what sources of waste or friction should be reduced but also what steps in the process allow them to tap into joy, excitement, meaning, purpose, etc.

- Create proactive structures for highlighting and displaying actions and artifacts that evoke positive emotions, such as shouts outs, examples of great performance, data sets that emphasize what good looks like (rather than just opportunities for improvement), etc.

- Human beings respond to 3 fundamental sources of motivation: fear-based motivation, competition-based motivation, and intrinsic/inspirational motivation.

- Motivation 1.0: Fear-based motivation is activated by threatening survival or a proxy and emphasizing the risk of loss (loss aversion).

- This focuses attention rapidly but is exhausting and evokes consistent, negative emotions.

- Motivation 2.0: Competition-based motivation is activated by 1) defining clear, consistent, and repeatable processes for accomplishing a goal; 2) outlining clear measurement of success or failure; 3) applying external incentives (“carrots” and “sticks”) to meeting the goal; and 4) making publicly visible where people fall along a spectrum of performance. Rewards flow to those who outperform their peers and/or exceed the goal the most.

- This focuses attention on meeting the goals, while neglecting other outcomes not being measured.

- Emotional response is mixed: pride if outperforming one’s peers, shame/frustration if not.

- The impact of carrots and sticks tends to fade over time – people stop exerting extra effort unless new carrots and sticks are applied.

- This form of motivation can incentivize gaming the system to “look good” in the numbers rather than increasing actual performance.

- Motivation 3.0: Intrinsic/inspiration-based motivation is activated by providing conditions that cause people to lean in and exert discretionary effort of their own volition. These conditions are:

- Autonomy – freedom to do work in one’s own way, within clear expectations/boundaries

- Mastery – providing opportunities to improve skills because the person wants to grow/improve as a personal goal

- Purpose – tapping into the deeper meaning/impact of work, giving people clarity on how their actions connect to “why I get out of bed in the morning”

- Connection/Community – allowing people to do work with others they enjoy spending time with

- Play – experiencing joy/fun and creativity in the act of doing work

- Many of the imbedded motivation systems and feedback loops in healthcare rely on motivation 1.0 and 2.0.

- The most effective leaders and programs actively cultivate as much motivation 3.0 as possible, which increases engagement, discretionary effort, and enjoyment of work.

Pro Tips

These materials are developed and created by IHQSE faculty and are the property of the Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety and Efficiency (IHQSE). Reproduction or use of these materials for anything other than personal education is strictly prohibited. Please contact IHQSE@cuanschutz.edu for questions or requests for materials.