Stress before Birth Affects Midlife Brain Circuits Differently in the Sexes

Anjali A. Sarkar, PhD Jun 7, 2021

“We know there are developmental roots to major psychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder—and that these roots begin in fetal development. We also know these disorders are associated with abnormalities in brain circuitry that regulates stress—circuitry that is intimately tied to regulating our immune system,” says Jill M. Goldstein, PhD, founder and executive director of the Innovation Center on Sex Differences in Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

In a new longitudinal study where individuals are followed over a course of 45 years, Goldstein and her colleagues provide concrete evidence that men and women whose mothers were significantly stressed during pregnancy respond differently to stress, 45 years later.

The study is based on a group of 80 individuals, half of whom were diagnosed with major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. “Given that the stress circuitry consists of regions that develop differently in the male and female brain during particular periods of gestation, and they function differently across our lifespans, we hypothesized that dysregulation of this circuitry in prenatal development would have lasting differential impact on the male and female brain in people with these disorders,” says Goldstein. “We were particularly interested in the role of the immune system, in which some abnormalities are shared across these disorders.”

Goldstein’s team shows exposure to proinflammatory cytokines in the womb—a measure of maternal stress—is closely associated with sex differences during midlife in brain activity and connectivity during response to negative stressful stimuli.

These findings were published in an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on April 5, titled, “Impact of prenatal maternal cytokine exposure on sex differences in brain circuitry regulating stress in offspring 45 years later.”

Exposure to stress before birth affects an individual’s risk for chronic diseases later in life. In an earlier study, the research group had linked maternal immune activity due to stress to sex differences in brain development in childhood and adulthood risk for clinical depression and psychoses.

In the current study, the investigators examine sex-dependent effects of in utero exposure to maternal proinflammatory cytokines on specific brain circuitry that regulate stress and immune function, that they hypothesize are retained across the lifespan.

“Inflammatory exposure in utero has been associated with some neurodevelopmental outcomes and a number of cardiovascular diseases later in life. However, it is the brain that is critically involved in our processing of stress…so it is one possibility that prenatal exposure might impact stress reactivity—and that might be a contributory factor to development of these chronic diseases,” says David Beversdorf, PhD, professor of radiology, neurology, and psychology at the University of Missouri, who is not part of the study. “Also, the incidence of cardiovascular diseases varies across gender, so it is critical to examine gender in this setting.”

Catherine Monk, PhD, professor of medical psychology at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, says, “This is a very rigorous study based on a truly unique data that allows for the prospective identification of a biological characteristic of the in utero environment—variation in maternal immune activation—that affects offspring’s brain functioning relevant for stress regulation when they are adults.”

Monk, who is who is not part of this study, adds, “The pathways for effects differ between males and females, underscoring contributions of sex-based biological differences to aspects of brain-behavior outcomes. Because different lifestyle factors are associated with changes in immune activity, such as stress, depression, illness, pollution, and compromised nutrition, these results suggest that health promotion for pregnant people, including mental health, may help them, as well as optimize development for the next generation. A key take home message from this study: Brain development begins before birth and is shaped by qualities of the mother’s life.”

Goldstein and her co-authors test their hypothesis in a group of 40 men and 40 women who were part of a New England Family Study that recorded data on data on maternal cytokine concentrations. The researchers followed these 80 men and women from before birth to midlife. Half the participants were diagnosed with at least one of three psychiatric conditions: major depressive disorder (14 women and 11 men), bipolar disorder (6 women and 3 men), or schizophrenia (1 woman and 6 men) while the other half had no psychiatric diagnosis.

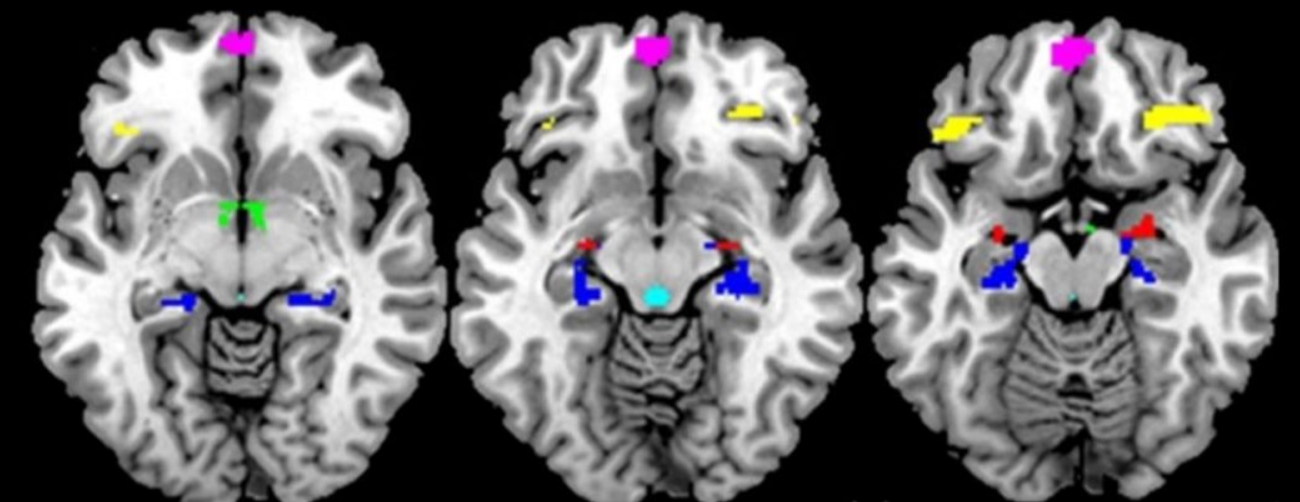

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)— that measures brain activity through differences in blood flow within and between different areas of the brain—conducted during a mildly stressful visual challenge showed that exposure to proinflammatory cytokines in the womb significantly affects activity in multiple brain regions and their crosstalk during response to the stressful stimuli in the adult offspring, now around 45 years old.

Arousal in brain regions such as the hypothalamus, amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex and the hippocampus are linked to the stress response of the brain and steroid hormones through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and gonadal axes.

“We study how these brain regions (subcortical arousal regions such as the hypothalamus, brainstem regions and amygdala) are connected to inhibitory control regions (like the anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal region, and hippocampus) and how these connections go awry in disorders like depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. We investigate this not only from a brain activity-connectivity point of view but also associated physiology such as hormonal response, autonomic nervous responses, and immune response,” says Goldstein.

Cytokines that promote inflammation (proinflammatory cytokines) and activate the HPA axis include the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6. The HPA axis, central to homeostasis, stress responses, energy metabolism, and behavior, serves as a junction for immune factors and steroid hormones that play a role in regulating stress responses.

Among other functions, the hypothalamus coordinates brain activity that regulates the release of stress hormones, like cortisol. The study shows lower maternal TNF-α levels are linked to higher hypothalamic activity in both sexes and higher functional connectivity between hypothalamus and anterior cingulate in men but not in women.

The paraventricular nucleus, a sub-region of the hypothalamus, has a high density of TNF-α receptors. “So, it was quite interesting to us that the region significantly affected by adverse maternal TNF-α levels was the hypothalamus in the offspring. There are substantial sex differences in the development of hypothalamic nuclei during gestation and thus this region is vulnerable to differential effects of in utero exposures depending on timing of exposure. Hypothalamic activity under negative stress is expected as the PVN is the key relay station for the regulation of the stress response. The anterior cingulate cortex is one of the regions in the brain that provides inhibitory control of activity in the hypothalamus. So, connectivity between these two regions is important for the regulation of arousal. When it goes awry it can lead to hyperarousal states,” says Goldstein. This is accompanied by overexpression of stress hormones such as cortisol.

The hippocampus, a brain region also endowed with a high density of TNF-α receptors, is important for inhibitory control of arousal as well as functions such as learning and memory. The authors show higher prenatal levels of IL-6 are associated with enhanced hippocampal activity in women but not in men.

The decrease in hippocampal activity in females due to increased prenatal stress result could compromise memory function in a sex-specific manner. “We are quite interested in this question because some of the regions that are affected by these in utero exposures in response to stress also regulate memory function,” says Goldstein.

When examined in relation to the inflammatory reducing effects of IL-10, the ratio TNF-α to IL-10 is associated with sex-dependent effects on hippocampal activity and functional connectivity with the hypothalamus.

The authors conclude that adverse levels of maternal proinflammatory cytokines and the balance of pro- to anti-inflammatory cytokines in the womb impact brain development of the offspring in a sexually dimorphic manner that persists throughout life.

“This demonstrates how enduring the impact of gestational stress can be on a developing fetus and the enormous importance of the immune system in sculpting neural circuits which predispose adult responding,” says Margaret M. McCarthy, PhD, professor and chair of the department of pharmacology at the University of Maryland, who is unrelated to this study.

Beversdorf says, “The investigators examined the relationship between fetal immune exposure and its impact on brain circuitry including stress circuitry in mid-life. The study provides what may be a key link in understanding sex differences in conditions such as cardiovascular disease, at least in regard to how they relate to prenatal exposures, and perhaps more broadly.”

These results, in conjunction with the team’s earlier studies emphasize the need to develop sex-specific psychiatric drug targets. “Given that these psychiatric disorders are developing differently in the male and female brain, we should be thinking about sex-dependent targets for early therapeutic intervention and prevention,” says Goldstein. Yet challenges abound in making this a reality.

“It has elements of convincing medicine/scientists and clinical trialists about the critical importance of designing the studies by sex in order to test for these effects. It has elements of convincing NIH, biotech companies, and the FDA that this is essential component of drug development. We need to educate and train our colleagues in how to do this as well as the next generation to incorporate the impact of sex into therapeutic development. This is absolutely critical for the goals of precision medicine,” says Goldstein.