Contact UCHealth

Brain and Spinal Cancers

Shared Content Block:

News feed -- crop images to square

Contact Children's Hospital CO

Clinical Trials

Make a Gift

What Are Brain and Spinal Cancers?

Brain tumors and spinal tumors are masses of abnormal cells that form in the brain or spinal cord. Together, the brain and spinal cord make up the central nervous system.

Although they rarely spread outside the central nervous system, both benign (non-cancerous) and malignant (cancerous) brain and spinal cord tumors can be life threatening, since they can press against and destroy normal brain and spinal tissue, which can lead to serious and sometimes fatal damage.

Brain and spinal cancers tend to be different in adults and children. They often form in different areas, develop from different types of cells, and may have different treatments and outlooks. Brain tumors and spinal cancers are the second most common cancers in children, after leukemia. They account for about 25% of all childhood cancer diagnoses.

According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 25,400 new cases of malignant tumors of the brain or spinal cord are diagnosed in the United States each year. Malignant brain and spine tumors result in approximately 18,760 deaths in the U.S. annually.

In Colorado, there are approximately 440 new cases of brain and spinal cancer diagnosed every year.

Brain and Spinal Cancer Prognosis and Survival Rates

Survival rates for brain and spinal tumors vary widely. The prognosis for a patient with brain or spine cancer depends on the type and location of the tumor and the age at which the patient is diagnosed.

According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the average five-year survival rate for patients with a malignant brain or spinal tumor is 36%. The 10-year survival rate is over 30%.

Why Come to CU Cancer Center for Brain and Spinal Cancers

As the only National Cancer Institute Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in the state of Colorado and one of only four in the Rocky Mountain region, the University of Colorado Cancer Center has doctors who provide state-of-the-art, patient-centered brain and spine tumor care and researchers focused on diagnostic and treatment innovations.

The CU Cancer Center is home to the Neuro-Oncology multidisciplinary clinic on the Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, Colorado, focusing on primary and metastatic brain tumors in outpatient and inpatient settings, paraneoplastic disorders, and neurological complications of cancer in adult patients. Multidisciplinary clinics offer patients an “all in one” approach to clinical care, overseen by world-class neurologists, medical oncologists, neurosurgeons, radiation oncologists, radiologists, genetic counselors, nurse navigators, and others who collaborate on both primary treatment and aftercare.

The Neuro-Oncology Program at Children’s Hospital Colorado is a world-renowned clinical and research center caring for nearly all pediatric CNS tumor patients in the Rocky Mountain Region. The multi-disciplinary team includes neuro-oncologists, neurosurgeons, radiation oncologists, neuroradiologists, neuropathologists, and associated specialists. The program conducts cutting-edge basic and clinical research and provides care for patients from diagnosis to long-term survivorship.

→ Five CU Cancer Center Researchers Receive Grants to Study Brain Tumors

There are numerous brain and spinal cancer clinical trials being conducted by CU Cancer Center members all the time. These trials offer patients additional options to traditional cancer treatment and can result in increased life spans.

For more information on pediatric brain and spinal cancers, and to learn more about the care team and conditions treated, visit the Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Program at Children’s Hospital Colorado.

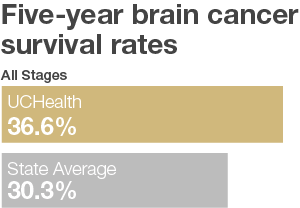

Our clinical partnership with UCHealth has produced survival rates higher than the state average for all stages of brain cancer.

Number of Patients Diagnosed – UCHealth 442 – State of Colorado 1,326

Number of Patients Surviving – UCHealth 262 – State of Colorado 402

*n<30, 5 Year Survival – (Date of diagnosis 1/1/2010–12/31/2014)

Types of Brain and Spinal Cancers

Different types of nervous system cells can become cancerous, and the type of cell affected determines the type of brain or spinal tumor. They are categorized by looking at the cells under a microscope. Doctors use this information to understand the expected growth pattern and speed, as well as which treatments may work best.

Tumors that begin in the brain or spine are called primary tumors, while tumors that begin in another part of the body and then spread to the brain or spine are called metastatic or secondary tumors. For adults, secondary brain and spine tumors are more common than primary tumors, and they are treated differently. This page pertains to primary tumors.

Brain tumors account for up to 90% of all primary central nervous system cancers.

Spinal tumors can be categorized as intradural tumors, which develop within the spinal cord or the covering of the spinal cord (dura), and vertebral tumors, which develop in the bones of the spine (vertebrae). Intradural tumors can be further classified as intramedullary tumors, which begin in the cells within the spinal cord, and extramedullary tumors, which form in the membrane surrounding the spinal cord or the nerve roots that branch out from the spinal cord.

Gliomas

Gliomas are brain and spine tumors that start in glial cells, the supporting cells of the brain. About 30% of all central nervous system (CNS) tumors are gliomas, and about 50% of CNS tumors in children are gliomas.

Astrocytomas are tumors that can form in the brain or spinal cord. They begin in glial cells called astrocytes. Astrocytomas may be slow-growing or aggressive. Astrocytomas in the brain can cause seizures, headaches, and nausea, and astrocytomas in the spinal cord can cause weakness and disability in the affected area. About 20% of all brain tumors are astrocytomas, and they are more common in children than adults. There are four grades of astrocytoma: non-infiltrating astrocytomas like pilocytic astrocytomas and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (Grade 1), low-grade diffuse astrocytomas and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas (Grade 2), anaplastic astrocytomas (Grade 3), and glioblastomas (Grade 4), also known as glioblastoma multiforme.

Ependymomas develop in the glial ependymal cells of the brain or spinal cord. Ependymal cells line the passageways where cerebrospinal fluid flows. Ependymomas are most common in young children, where they cause headaches and seizures. In adults, ependymomas are most likely to form in the spinal cord and may cause weakness in the parts of the body controlled by the nerves affected by the tumors.

Choroid plexus carcinomas are rare, malignant brain tumors that occur primarily in children. They begin near the brain tissue that secretes cerebrospinal fluid and can affect the function of nearby structures in the brain. As they grow, these tumors can cause excess fluid in the brain (hydrocephalus), irritability, nausea or vomiting, and headaches.

Oligodendrogliomas are rare tumors that form in brain glial cells called oligodendrocytes. These cells are responsible for making myelin, the protein- and lipid-rich substance that surrounds nerves. They usually grow slowly, but they can become more aggressive over time. Extremely aggressive oligodendrogliomas are known as anaplastic oligodendrogliomas.

Embryonal Tumors

Embryonal tumors are malignant tumors that develop in fetal (embryonic) nerve cells in the central nervous system, including both the brain and spinal cord. About 10–20% of all brain tumors in children are embryonal tumors. They are most common in babies and young children, and they are rare in adults. Embryonal tumors tend to grow quickly. In the past, some embryonal tumors were referred to as primitive neuroectodermal tumors.

Medulloblastomas are the most common type of embryonal tumors. They are fast-growing tumors that begin in the neuroectodermal cells of the cerebellum.

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors are rare tumors that form in the brains or spinal cords of infants and young children.

Embryonal tumors with multilayered rosettes are rare, aggressive, malignant tumors that usually develop in the largest part of the brain (the cerebrum) in infants and young children.

Pineoblastomas are rare, aggressive tumors that form in the cells of the pineal gland, which is located in the center of the brain and produces the hormone melatonin, which helps regulate the body’s sleep-wake cycle. Pineoblastomas can occur at any age, but they occur most often in young children. These tumors may cause headaches, sleepiness, and changes in the way the eyes move.

Other Brain and Spinal Tumors

Acoustic neuromas, also known as vestibular schwannomas or neurilemmomas, are benign and usually slow-growing tumors that develop on the vestibular nerve leading from the inner ear to the brain. Pressure from an acoustic neuroma can cause hearing loss, ringing in the ear, and unsteadiness.

Craniopharyngiomas are rare, benign brain tumors that develop near the pituitary gland. Craniopharyngiomas are usually slow-growing and occur most often in children and older adults. They may affect growth in children and can cause changes in vision, fatigue, excessive urination, and headaches.

Meningiomas are tumors that form in the meninges, the layers of tissue that surround the outer part of the brain and spinal cord. Meningiomas are usually benign and make up about a third of all primary brain and spinal tumors. They are the most common primary brain tumors diagnosed in adults and occur about twice as often in women as in men. People with a family history of neurofibromatosis type 2 may be more likely to develop meningiomas.

Gangliogliomas are slow-growing tumors that contain both neurons and glial cells. They are very rare in adults.

Pituitary tumors, also called pituitary adenomas, start in the pituitary gland. Although they are almost always benign, they can cause problems if they grow large enough to press on nearby brain structures or if they make too much of any kind of hormone. They are more common in teenagers than in children.

Germ cell tumors are rare tumors that develop from germ cells. During normal prenatal development, germ cells travel to the ovaries or testicles and develop into egg or sperm cells. But sometimes germ cells travel to abnormal locations, such as the brain, where they may develop into germ cell tumors. Germ cell tumors of the nervous system usually occur in children or teens and typically form in the pineal gland or near the pituitary gland.

Lymphomas begin in white blood cells called lymphocytes. Most lymphomas start in other parts of the body, but some form in the central nervous system. When this occurs, they are called primary CNS lymphomas. They are very rare in children and usually occur in adults with weakened immune systems.

Chordomas are rare tumors that start in the bone at the base of the skull or the lower end of the spine. Although they don’t technically start in the central nervous system, they can injure nearby brain structures or the spinal cord as they grow.

Risk Factors for Brain and Spinal Cancer

Brain and spinal cancers develop when cells begin to multiply rapidly, accumulating to form a lump or mass called a tumor. Although most brain and spinal tumors are not linked with known causes or risk factors, researchers have identified some hormonal, lifestyle, and environmental factors that may increase a person’s risk of developing a brain tumor or spine tumor.

Radiation exposure: The biggest environmental risk factor for brain and spine tumors is radiation exposure, usually from radiation therapy to treat another condition or type of cancer, such as leukemia.

Family history: Brain or spinal cancers usually do not run in families, but some rare familial cancer syndromes and genetic disorders are associated with increased risk. These include neurofibromatosis type 1, also known as von Recklinghausen disease; neurofibromatosis type 2; tuberous sclerosis; von Hippel-Lindau syndrome; Li-Fraumeni syndrome; Turcot syndrome, also known as brain tumor-polyposis syndrome; Gorlin syndrome, also known as basal cell nevus syndrome; Cowden syndrome, Lynch syndrome, and BRCA2 gene mutations.

Weakened immune system: People with weakened immune systems have a higher chance of developing lymphomas of the brain or spine.

Chemical exposure: Some studies have shown a possible link between exposure to vinyl chloride (a chemical used to manufacture plastics), petroleum products, and other industrial chemicals and an increased risk of brain tumors.

Age: Brain and spinal tumors are most common in older adults.

Gender: Men are generally more likely than women to develop brain or spinal cancer. However, some specific types of tumors, such as meningioma, are more common in women.

Viral infections: Infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is most widely recognized as the virus that causes mononucleosis or “mono,” increases the risk of primary CNS lymphoma. Other research has shown that high levels of a common virus called cytomegalovirus may also be associated with a higher risk for brain or spinal cancer.

Symptoms of Brain and Spinal Cancer

Unlike many other cancers, the prognosis for patients with brain or spinal cord tumors depends more on their age, the type of tumor, and its location, rather than how early it is detected. However, earlier detection and treatment is still likely to be helpful, so it’s important to understand the most common symptoms.

Many brain tumors lead to an increase in pressure inside the skull (known as intracranial pressure), which may be caused by the tumor itself, swelling in the brain, or blockage of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid. This increased pressure can lead to other symptoms, most commonly new or worsening headaches accompanied by nausea or vomiting.

Because there are so many different types of brain and spine tumors, each may cause different signs and symptoms, especially depending on where they are located and how quickly they are growing. Besides raised intracranial pressure, other symptoms that can be associated with brain or spinal tumors include:

- New or worsening headaches.

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Problems with balance, walking, or coordination.

- Crossed eyes, blurred vision, or other vision problems.

- Hearing problems.

- Weakness or numbness of part of the body, often on just one side.

- Trouble swallowing.

- Difficulty synchronizing eye movements.

- Weakness of some facial muscles or facial numbness or pain.

- Personality or behavior changes.

- General confusion or loss of memory.

- Problems with speech or understanding.

- Seizures.

- Drowsiness or fatigue.

- Coma.

- Problems with bladder or bowel control.

- Developmental delays.

- Loss of appetite or unexplained weight loss.

- Increased head size or bulging of the soft spots of the skull (fontanelles) in children.

- Early or delayed puberty.

- Back pain that is worse at night or that radiates to other parts of the body.

- Loss of sensitivity to pain, heat, or cold.

- Muscle weakness or paralysis.

- Lactation or altered menstrual periods in women.

- Sudden growth in hands and feet in adults.

- Staring or repetitive automatic movements, such as a squint or neck tilt.

These symptoms can also be caused by conditions other than brain or spinal cancer.

There are no widely recommended tests to screen for brain and spinal cord tumors. However, people with certain inherited syndromes (such as those listed in the Risk Factors for Brain and Spinal Cancer section) should alert their doctors, since there may be surveillance plans in these cases, and monitor for any symptoms.

Diagnosing Brain and Spinal Cancer

Most brain and spine tumors are diagnosed when a person visits their doctor because they are experiencing symptoms. This visit will likely involve both a discussion of the patient’s medical history, a physical exam, and a neurological exam to assess brain and spinal cord function by testing the patient's reflexes, muscle strength, vision, eye movement, hearing, balance, coordination, and alertness. If a doctor detects an abnormality, they may recommend further tests to determine whether the patient has cancer or a benign tumor. Based on their findings, the doctor may also refer the patient to a specialist, such as a neurologist, medical oncologist, or neurosurgeon.

The diagnostic process may involve many steps, including all or some of the following:

Imaging Tests for Brain and Spinal Cancer

Imaging tests can show where the tumor is located and whether it has spread from the original site. The images are reviewed by a radiologist, a doctor who specializes in interpreting imaging tests.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are the imaging tests doctors use most often to look for brain and spinal cancer. These scans will almost always reveal a tumor, if one is present, as well as giving the doctor an idea about what type of tumor it might be.

Special types of MRIs for brain tumors and spine tumors include magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and magnetic resonance venography (MRV), which are used to look at the blood vessels in the brain. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) can be performed during an MRI to measure biochemical changes in an area of the brain and can be helpful in determining the type of tumor. During magnetic resonance perfusion, also known as perfusion MRI, a contrast dye is injected into a vein to show the amount of blood going through different parts of the brain and tumor. After diagnosis, doctors may use a functional MRI (fMRI) to look for tiny blood flow changes in an active part of the brain. This test can be used to discover what part of the brain handles functions such as speech, thought, sensation, or movement, telling them which parts of the brain to avoid during surgery or radiation therapy.

There are also special types of CT scans for brain and spinal tumors. During CT angiography (CTA), a contrast dye is injected through an IV line to create detailed images of the blood vessels in the brain.

In some cases, the doctor may also order a positron emission tomography (PET) scan to aid in diagnosis. They may also use x-rays, such as a cerebral arteriogram, also called a cerebral angiogram. This x-ray or series of x-rays shows the arteries in the brain. Some patients may also have a chest x-ray to check for tumors in the lungs if the doctor suspects the cancer may have started there.

Biopsies for Brain and Spinal Cancer

During a biopsy, a doctor extracts samples of tissue from the suspected tumor. These are sent to a laboratory for analysis by a pathologist to determine whether the cells in the sample are cancerous. They may also test for certain gene or chromosome changes in the tumor’s DNA. There are different kinds of biopsies, and the type of biopsy a patient receives is determined by several factors, including the size and location of the tumor, the number of tumors, and the type of cancer suspected.

During a stereotactic needle biopsy, the neurosurgeon makes a small incision in the scalp and drills a small hole in the skull. Then they use MRI or CT imaging to insert a thin, hollow needle into the tumor to remove small samples of tissue. Stereotactic needle biopsies are most often performed for tumors in hard-to-reach or sensitive areas that could be damaged by a more extensive operation.

If the doctor thinks the tumor can probably be treated with surgery, they may perform a surgical or open biopsy called a craniotomy to remove all or most of the tumor, which is then examined by a pathologist.

A biopsy is often the only way to definitively diagnose cancer. However, sometimes imaging or lab tests may make the diagnosis so obvious that a biopsy is not required.

Lumbar Puncture for Brain and Spinal Cancer

During a lumbar puncture or spinal tap, a doctor uses a needle to take a sample of cerebrospinal fluid from the lower back to look for tumor cells, blood, or tumor markers. Tumor markers (also called biomarkers) are substances found in higher levels in the blood, urine, spinal fluid, plasma, or other bodily fluids of patients with certain types of cancers. Lumbar punctures are most often used to test the extent of tumors that commonly spread through the cerebrospinal fluid. They are also used for patients with suspected CNS lymphomas.

Prognostic Factors for Brain and Spinal Cancer

Unlike most other types of cancer, brain and spinal cancers rarely spread to other parts of the body (though they can spread to other parts of the central nervous system). Instead, these cancers are dangerous because they can interfere with essential brain and nervous system functions. Because of this, they do not have a formal staging system.

However, there are a number of important factors that help determine a person’s outlook, treatment options, and prognosis. These include:

- The patient’s age.

- Whether the tumor is affecting normal brain functions and everyday activity (described as the patient’s functional level).

- The type of tumor.

- The location and size of the tumor.

- The grade of the tumor (how quickly the tumor is likely to grow, based on how the cells look under a microscope), usually on a scale of 1–4.

- The presence of certain gene mutations or other changes.

- Whether and how much of the tumor can be removed by surgery.

- Whether or not the tumor has spread through the cerebrospinal fluid to other parts of the brain or spinal cord.

- Whether or not tumor cells have spread beyond the central nervous system.

- Symptoms the patient is experiencing and how long they have persisted.

- Whether the tumor returns after treatment (called recurrence).

Treatments for Brain and Spinal Cancer

The treatment for brain and spinal tumors is customized to each patient. Brain and spinal cancer care teams may include multiple health care specialists, including primary care providers, medical oncologists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, radiation oncologists, radiologists, endocrinologists, genetic counselors, physical therapists, patient navigators, and nurse navigators, as well as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and rehabilitation specialists. CU Cancer Center doctors offer specialized care for patients with brain and spinal cancer.

The primary treatments for brain and spinal cancer are surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted drug therapy, and alternating electric field therapy. Most patients receive one or more of these treatments, and some may also be eligible to participate in clinical trials — research studies of new or experimental procedures or treatments.

Surgery for Brain and Spinal Cancer

Surgery is a primary treatment for brain and spinal tumors and is often the only treatment needed for a low-grade tumor.

A craniotomy is the most common surgical approach to treat brain tumors. During this procedure, a neurosurgeon, often guided by MRI or CT scans, makes an incision in the scalp and then uses a drill to remove the piece of skull covering the tumor. The surgeon may also need to cut into the brain itself to reach the tumor. Once they locate the tumor, the neurosurgeon will remove the tumor in one of a few different ways, depending on how hard or soft it is and the number of blood vessels it contains. Many tumors can be excised (removed) with a scalpel or special scissors, while soft tumors are often removed with a suction device. In other cases, a handheld ultrasonic aspirator is used to break up the tumor and suction it out. Afterward, the piece of skull is put back in place and attached with titanium screws and plates, wires, or special stitches.

During a craniotomy, the patient may be under general anesthesia or may be awake for at least part of the procedure (with the surgical area numbed) if the surgeon needs to assess brain function during the operation.

When a tumor blocks the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, it can increase pressure inside the skull. Although surgery to remove the tumor can help with this, there are other surgical options to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid if tumor removal isn’t possible. The neurosurgeon may place a silicone tube called a shunt (also known as a ventriculoperitoneal or VP shunt) to drain the fluid from the brain into the abdomen or, occasionally, the heart (this is called a ventriculoatrial shunt). Another option to treat blocked cerebrospinal fluid flow in some cases is an endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV). During this procedure, the neurosurgeon drills a small hole in the skull and creates an opening in the floor of the third ventricle in the middle of the brain to allow the fluid to flow again.

Radiation Therapy for Brain and Spinal Cancer

Radiation therapy uses high-energy beams, such as x-rays, to kill cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in radiation therapy is a radiation oncologist. Radiation for brain and spinal tumors may be used after surgery to destroy any remaining tumor cells or as the main treatment if surgery to remove the tumor is not an option.

External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the most common radiation treatment for brain and spine cancer and uses a machine located outside the body to focus a beam of x-rays at the tumor site. Since high doses of radiation can damage normal brain tissue, radiation oncologists aim to deliver the radiation to the tumor while exposing the surrounding brain tissue to the lowest possible doses. One form of EBRT that is used for brain and spine cancer is stereotactic radiosurgery, which uses multiple beams of highly focused radiation to kill cancer cells in a small, specific area. The individual beams of radiation aren't especially powerful, but the point at which all the beams meet at the tumor receives a high dose of radiation.

Brachytherapy, or internal radiation therapy, involves the insertion of radioactive pellets directly into or near the tumor. These pellets, also called seeds, are each about the size of a grain of rice and give off radiation only around the affected area.

Whole brain and spinal cord radiation therapy, also called craniospinal radiation, is sometimes used for tumor types with a high likelihood of spreading along the covering of the spinal cord (the meninges) or into the cerebrospinal fluid. In these cases, radiation may be given to the whole brain and spinal cord. Embryonal tumors are more likely than other brain and spine tumors to require craniospinal radiation.

Chemotherapy for Brain and Spinal Cancer

Chemotherapy uses powerful medicine to kill tumor cells. Chemotherapy drugs are most often taken in pill form or injected into a vein. For some types of brain and spinal tumors, chemotherapy may also be delivered directly into the cerebrospinal fluid.

The chemotherapy drug used most often for patients with glioblastoma and high-grade glioma is called temozolomide (Temodar), which is taken as a pill.

Patients who have surgery to remove their tumors may receive chemotherapy via Gliadel Wafers. The dissolvable wafers contain the chemotherapy drug carmustine (BiCNU) and are placed in the area where the tumor was removed during surgery. Unlike intravenous or oral chemotherapy, which affects all areas of the body, this type of chemo concentrates the drug at the tumor site so the patient experiences fewer side effects.

Many other oral and IV chemotherapy medicines are used for pediatric brain tumors.

Targeted Drug Therapy for Brain and Spinal Cancer

Targeted drug therapy focuses on the specific proteins, genes, or tissue environments in cancer cells while limiting damage to healthy cells and tissues. Here are some examples that are already used in standard practice; there are others that are also frequently used and many more in clinical trials.

Bevacizumab (Avastin, Mvasi, and Zirabev) is a synthetic version of an immune system protein called a monoclonal antibody. It targets a specific protein that helps tumors form new blood vessels (a process called angiogenesis), which they need to grow. It is administered through an IV to treat some types of gliomas and may also be effective in treating recurrent meningiomas.

Everolimus (Afinitor) blocks a cell protein called mTOR, which helps cells grow and divide into new cells. It is administered orally via pill and used to shrink or slow the growth of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas that cannot be removed completely with surgery.

Larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) is not specific to a certain type of tumor. Instead, it targets a specific genetic change called an NTRK fusion that is found in a range of tumors, including some brain and spine tumors.

Alternating Electric Field Therapy for Brain and Spinal Cancer

This treatment uses a non-invasive, portable device called Optune to create alternating electrical fields, also called tumor-treating fields. The fields interfere with the parts of a cell that are needed for cancer cells to grow and spread. The treatment is recommended for patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent glioblastoma and is often performed in tandem with or instead of chemotherapy.

During alternating electric field therapy, the patient’s head is shaved, and four sets of electrodes are placed on the scalp. The electrodes are attached to a battery pack that is housed in a backpack and are worn for most of the day.

The University of Colorado (CU) Cancer Center partners with UCHealth, Children’s Hospital Colorado, and Rocky Mountain Regional VA to provide clinical care. Please make an appointment with one of our clinical partners to be seen by a CU Cancer Center doctor.

UCHealth Cancer Care - Anschutz Medical Campus

1665 Aurora Court Anschutz Cancer Pavilion

Aurora, CO 80045

720-848-0300

UCHealth Cherry Creek Medical Center

100 Cook Street

Denver, CO 80206

720-848-0000

UCHealth Cancer Center - Highlands Ranch

1500 Park Central Drive

Highlands Ranch, CO 80129

720-516-1100

UCHealth Lone Tree Medical Center

9548 Park Meadows Drive

Lone Tree, CO 80124

720-848-2200

Children's Hospital Colorado:

13123 East 16th Avenue

Aurora, CO 80045

720-777-6740

Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center:

1700 North Wheeling Street

Aurora, CO 80045-7211

303-399-8020

Latest in Brain and Spinal Cancer from the CU Cancer Center

Loading items....

Information reviewed by Adam Green, MD, in May 2022.