Congenital Inguinal Hernia

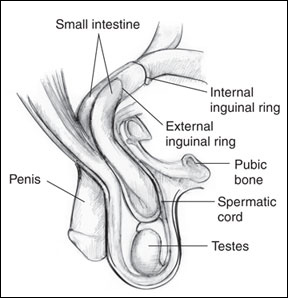

An inguinal hernia occurs when a sac-like projection of the abdominal cavity extends down the groin on one or both sides toward the scrotum (in boys) or labia (in girls). Sometimes a portion of an abdominal organ (bowel or viscera) migrates down the hernia sac, causing a bulge or visible lump to be seen in the groin. Inguinal hernias are present in 10-30% of preterm infants and 1-5% of full-term infants, with boys outnumbering girls.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

An inguinal hernia is a swelling in the groin that comes and goes or can be pushed in (reduced). Inguinal hernias that appear at less than three months of age are the most concerning because of the risks of damage to the herniating bowel or viscera

Treatment and Prognosis

Most hernias in children are diagnosed and managed without difficulty. However, an inguinal hernia that becomes hard and cannot be pushed in may be “incarcerated” or “strangulated” and needs urgent evaluation.

A hernia is repaired by carefully separating the hernia sac from the associated blood vessels and, in boys, the vas deferens (the tube where sperm will travel after the child reaches puberty). The next step is to divide the hernia sac and tie it off at the level of the abdominal cavity.

Inguinal hernia in a male. Diagram courtesy of National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

During surgery for an inguinal hernia, it is important to check for the presence of a hernia on the opposite side, especially if the child is less than five years old or has multiple medical problems, congenital heart disease, or a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (a plastic tube that drains fluid from around the brain into the abdominal cavity). The easiest way to check for a hernia on the opposite side is to place a plastic tube or port into the hernia sac and inflate the abdominal cavity with carbon dioxide. A long thin camera (laparoscope) is then advanced through the port and into the abdominal cavity to visualize whether or not there is a hernia on the opposite side. If an inguinal hernia is found on the opposite side, it should be repaired under the same anesthetic. This prevents the need for another operation in the future.

Sometimes, preterm infants (born at less than 38 weeks) who undergo an inguinal hernia repair must be observed overnight for breathing problems. Post-operative breathing problems in pre-term infants are thought to result from a combination of immature respiratory control mechanisms, residual affects of anesthetic drugs, and ventilatory muscle fatigue. These types of breathing problems can occur unexpectedly several hours after a surgical procedure is performed under general or spinal anesthetic. For this reason, these infants are monitored overnight after their surgery.

This information is provided by the Department of Surgery at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. It is not intended to replace the medical advice of your doctor or healthcare provider. Please consult your healthcare provider for advice about a specific medical condition.