IHQSE Model for Change

eQuip the Team for Change

eQuip the Team for Change

Background

There are two parts to successful improvement efforts. The first is to deeply understand your problem (achieved through the Investigation phase) and to design perfect solutions (achieved as you Hone the Intervention). The second step, is to lead your people through successful change.

Remember 3 key lessons to change: Humans do not like change. Change is very, very hard for people. We tend to be complacent with a "good enough" state.

In order to combat the above, you need to spend a significant amount of energy on the 8 steps of successful change. Then, you need to understand and address sources of resistance.

A great sense of urgency requires three components: a story, data, and vision.

Stories

A powerful story grabs people’s attention and demands they listen.

The story can be of a patient who had a bad outcome or someone who had a good outcome. It’s often more powerful if it’s a bad outcome but positive ones work as well to build positive energy. Sometimes you’ll have both. A negative one in the beginning of the presentation and a positive one at the end to show how it could work if we all made the necessary changes.

It should take less than 30 seconds or so to tell. A 5-minute story loses its impact.

Data to Show the Scope of the Problem

Stories, unfortunately have a short half-life. People don't remember them for long, and as such, they are not great long-term motivators of change.

Additionally, while stories may be attention-grabbing, they don't speak to the scope of the problem. E.g., if this happened one time 20 years ago, that is tragic but not enough to compel me to change my behavior.

Data allows you to share the scope of the problem.

Vision

A vision is your ideal future state. It's what you aspire to become in the future -- as a person, group, or organization.

Great visions are aspirational (achieving greatness, things currently out of reach) and inspirational (motivate people to try to attain it).

Visions are not goals. Goals are achievable, concrete outcome you strive to achieve IN PURSUIT OF THE VISION.

Visions are generally not attainable. You will never be the achieve zero preventable harm (that's a vision, not a goal) but you can certainly set goals that, when achieved, get you closer and closer to that vision.

Most organizations have vision statements. Few have internalized them. Even fewer lead to them. This is one reason why change so often fails. To succeed you need to lead your change toward a powerful vision.

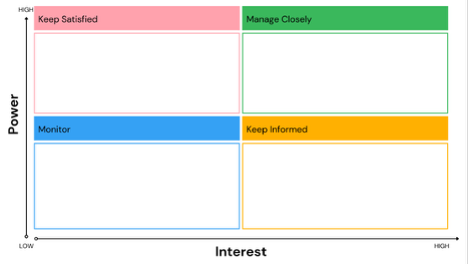

- You should have a core project team, usually 3 – 5 individuals who are deeply engaged in the work and impacted by the outcome. This group should be meeting regularly (every 2 weeks) and pursuing project work in the interim. High Interest

- You will also have Ad Hoc team members to gain trust, expertise, and insight, – these may be content experts or experts in different specialties or disciplines. They should be consulted as needed and may join meetings every 1 –2 months. Medium Interest

- You should identify an executive stakeholder (s). These are people who have high power, and who are interested in the outcome of the work, but not the day to day operations. These stakeholders should be consulted to remove barriers, offer resources, and to celebrate your outcomes and success. High Power

- Remember to include the ‘cool kids.’ These are the influencers, the people others look to for their cue of how to react. These people usually do not have formal titles. They play a crucial role in helping you create and lead the effort.

Principles of Motivation

- Human beings respond to 3 fundamental sources of motivation: fear-based motivation, competition-based motivation, and intrinsic/inspirational motivation.

- Motivation 1.0: Fear-based motivation is activated by threatening survival or a proxy and emphasizing the risk of loss (loss aversion).

- This focuses attention rapidly but is exhausting and evokes consistent, negative emotions.

- Motivation 2.0: Competition-based motivation is activated by 1) defining clear, consistent, and repeatable processes for accomplishing a goal; 2) outlining clear measurement of success or failure; 3) applying external incentives (“carrots” and “sticks”) to meeting the goal; and 4) making publicly visible where people fall along a spectrum of performance. Rewards flow to those who outperform their peers and/or exceed the goal the most.

- This focuses attention on meeting the goals, while neglecting other outcomes not being measured.

- Emotional response is mixed: pride if outperforming one’s peers, shame/frustration if not.

- The impact of carrots and sticks tends to fade over time – people stop exerting extra effort unless new carrots and sticks are applied.

- This form of motivation can incentivize gaming the system to “look good” in the numbers rather than increasing actual performance.

- Motivation 3.0: Intrinsic/inspiration-based motivation is activated by providing conditions that cause people to lean in and exert discretionary effort of their own volition. These conditions are:

- Autonomy – freedom to do work in one’s own way, within clear expectations/boundaries

- Mastery – providing opportunities to improve skills because the person wants to grow/improve as a personal goal

- Purpose – tapping into the deeper meaning/impact of work, giving people clarity on how their actions connect to “why I get out of bed in the morning”

- Connection/Community – allowing people to do work with others they enjoy spending time with

- Play – experiencing joy/fun and creativity in the act of doing work

- Many of the imbedded motivation systems and feedback loops in healthcare rely on motivation 1.0 and 2.0.

- The most effective leaders and programs actively cultivate as much motivation 3.0 as possible, which increases engagement, discretionary effort, and enjoyment of work.

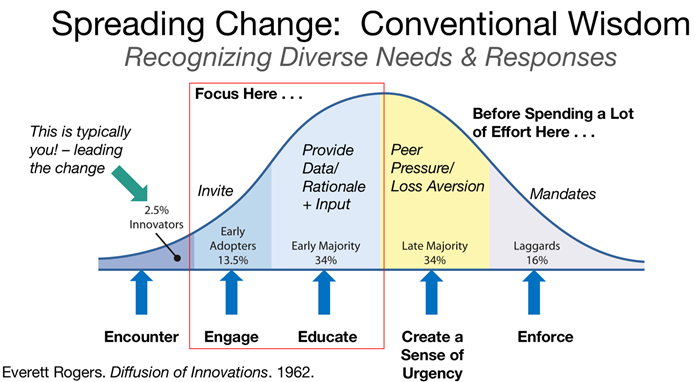

Diffusion of Innovation

- Change invokes an inherently social psychology – separate from the change roadmap that supports any change initiative.

- Not all people encountering something new will perceive and react to it in similar ways.

- People affected by the change are often talking to peers about it more than they spend time engaging with leaders or the official communications about change.

- Good leaders vary their engagement approaches to engage with diverse reactions to change.

- Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Curve describes common reactions to change, along a spectrum of feeling/thinking that people experience when contemplating something new/different.

- Building an effective guiding coalition requires inviting/engaging innovators and early adopters—those who are excited to support the change without much question. Having this group alone will not ensure success because it is a small proportion of the population experiencing the change.

- An effective coalition also requires members of the early majority – skeptics who will prefer not to change because they are already busy, don’t see immediate relevance, or worry that the change will disrupt the status quo in unhelpful ways. This group desires data and strong rationale that support change and will only get on board once these are provided. Often this group also wants local proof of efficacy, not a paper or case study from other organizations.

- Avoid spending significant time when launching a change on convincing the late majority and laggards—the loudest critics. These 2 groups seek to avoid change at almost all costs, and will work to obstruct change regardless of data, rationale, etc.

- After engaging and winning over skeptics in the early majority, create a sense of urgency for the late majority through peer pressure provided by the early majority members who become ambassadors for the change. Late majority fears being left behind by their skeptical peers in the early majority.

- Engage with the laggards last, by creating new rules/policies or forcing functions that require them to adopt the new way.

Awareness Campaign

- Logo: Your logo should capture who you are as a team, what you represent, and become a visual symbol for your project work. It should invoke an emotional response from your team members -- consider use of humor, witty phrases, colors and symbols that represent your team. Consider use of AI tools (copilot, Jasper, ChatGPT) to support your visual dreams.

- Importance of a Movement: Initiatives that require people to change their behavior often fail because change is hard! This is, in part, because we tend to focus our energy on communicating the desired change. Communication is important but not enough.

- You need to create a movement:

- Communication is something you do to people.

- A movement is something people choose to do.

- A movement is a coordinated group action focused on a desired change.

- Movements have larger communal, social, and cultural impacts.

- The movement inspires people to become part of something bigger than the change itself.

- It transcends the project, becoming more about people than the initiative.

- A movement is a coordinated group action focused on a desired change.

- Movements arise, not from a call to action, but from an emotion.

- It starts with dissatisfaction with the current state and the belief that the current structures will not address the problem.

- Then, you need to provide a positive vision and path forward that's tangible and achievable.

- Typically start small with a passionate group of enthusiasts who provide some short-term wins to demonstrate the change. This brings in influencers who can further grow the movement. (leadership lessons from a dancing guy)

- You need to create a movement:

- The Kickoff Campaign: This should be an event that marks the start of your intervention. It should feel celebratory (consider food, music, prizes, ribbon cutting) and also symbolic, signaling to your team that this is the start of a new era. Plan this in advance, set a date, a short amount of time assuming it will occur during the work day (15 minutes over lunch), and ensure your people know about it.

- Barriers to change take many forms: learning new habits, taking a risk to try a new way, fear of looking incompetent in front of peers/bosses, being initially slower/less efficient at a new task, fear of the unknown, burnout, metrics that incentivize the current approach, peer pressure to conform to the status quo, etc.

- Creating effective change requires helping people overcome barriers as easily and quickly as possible.

- Designing an effective change initiative requires three steps related to removing barriers:

- Identify barriers people are likely to encounter before they experience those barriers.

- This needs to be done before a program/change initiative launches.

- Design ways to remove the barriers or minimize the demoralization that occurs when people experience a barrier.

- This also needs to be done prospectively as much as possible.

- Set expectations for experiencing successes and barriers at a level that means people will say to themselves, "that was easier/less bad than I thought" when they try the new approach/program.

- Identify barriers people are likely to encounter before they experience those barriers.

Celebration

- This celebration begins to bring in the late majority who are sympathetic but also skeptical. Showing them positive momentum can bring them into the movement.

- These wins emphasize the behavior you want to see and the outcomes you intend to grow. It allows people to experience the change they want.

- Celebrations

- Excellence in Diagnosis (Ex Dx, Great Catch, etc.) Awards

- This is an awards program that should encourage people to highlight the great work of others in diagnosis.

- These should be sent out via email to the entire group with the nominating person.

- The goal is to generate at least one of these per week.

- See celebration module for more information.

- Milestones

- For example: 10th case review, 50th case review, first intervention based on findings from case review.

- Excellence in Diagnosis (Ex Dx, Great Catch, etc.) Awards

Individual Appreciation

- Appreciation/positive feedback is under-represented in most forms of institutional feedback to individuals, including case review

- Historical focus has been on errors, gaps in performance, negative outliers compared to standards/expectations

- Most common “positive” feedback is reframing negative feedback with positive language (”opportunity for improvement” - i.e., this is bad/below standard but we will talk about it as an “opportunity” rather than a deficit) or non-specific kudos (”nice job” or ”thanks for good/hard work”).

- Science from education to coaching to safety supports that learning, motivation, performance, and culture benefit from increased positive feedback and appreciation at individual and team level.

- While offering appreciation for outcomes can highlight what excellence looks like, behavior change is most impacted by providing specific, timely, positive feedback on behaviors that support the outcome (not only negative feedback on what not to do).

- Optimal ratio of positive to negative/constructive feedback is 3-5 (+) to 1 (-) to maximize learning, performance, and morale.

- Appreciation formula is more effective than improvising or relying on positive platitudes like ”nice job“ or “keep up the good work.”

- Formula = “Thank you (name of person or group) for (behavior that positively impacted me/the DxEx program), because (here’s how it made a difference to me/the DxEx program).”

- Relying on randomly encountered opportunities to provide appreciation/positive feedback is less powerful than designing authentic, deliberate, regular (predictable and spontaneous) mechanisms for appreciation.

- Resistance is often perceived as an inconvenient barrier to smooth implementation of a plan or new way of doing things.

- In reality, engaging in any sort of change will evoke resistance as a natural outcome of the leadership effort. Thus, navigating resistance more effectively is a key leadership skill.

- David Rock's SCARF model is based on neuroscience regarding hte underlying emotional responses people have when experiencing change and common sources of resistance.

- When facing skepticism from an individual, try to uncover and name (for yourself an the other person) the element of the SCARF model driving skepticism.

- Status

- Certainty

- Autonomy

- Relatedness - to my job/goals/values vs. to my cherished relationships

- Fairness

- Decide whether to address that source of skepticism directly or pivot to "topping up" another element of the SCARF model.

- If directly addressing a SCARF domain, discuss with the other person how you can address it together.

- E.g., "it sounds like you are worried this new process with create more hassle and chaos in your daily work (certain concern). Let's work together to make sure the process works smoothly and you know exactly what to expect (top up certainty and autonomy)."

- If pivoting to another SCARF domain, acknowledge the other perso's concern and then direct attention to "topping up" another domain.

- "it sounds like your group feels the way in which this initiative has unfolded is deeply unfair (fairness concern)."

- "I'm sorry things have played out this way (acknowledge)."

- "Let's look at how re-engaging now could position you all as leaders (pivot to status)."

- "Let's work together to identify ways in which your group can have more autonomy in shaping the current phase of implementation (pivot to autonomy)."

Pro Tips

These materials are developed and created by IHQSE faculty and are the property of the Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety and Efficiency (IHQSE). Reproduction or use of these materials for anything other than personal education is strictly prohibited. Please contact [email protected] for questions or requests for materials.